You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Lots of colleges and universities acknowledge troublesome -- if relatively small -- gaps in pay among men and women professors, and among white and minority professors. But it’s a hard thing to study and address, given the many variables and competing theories involved. So a new, comprehensive study of tenure-line faculty salaries at the University of California at Berkeley -- along with an administrative pledge to close revealed gaps -- is getting a lot of attention.

“There is so much goodwill on our campus -- what we were missing was information,” said Janet Broughton, vice provost for faculty at Berkeley and chair of the joint administration-Academic Senate committee that conducted the study. “Now that we have it, I think we will be able to move forward in many ways, whether it’s helping a department chair build a culture that is richly inclusive or designing a salary program that can help us progress toward our equity ideals.”

The ultimate goals, Broughton said, are to make sure Berkeley’s pay practices are in line with legal nondiscrimination standards, and to offer “salaries as similar as possible to the faculty within each discipline who are of equal accomplishment.”

Berkeley ran the data using two models, due to long-standing debate about which is most appropriate: one controlling for experience, field and rank, and the second controlling for just experience and field. Both models show that women earn less than their comparable colleagues who are white men, university-wide: 1.8 percent less, controlling for rank, and 4.3 percent less, not controlling for rank. There’s a smaller gap for ethnic minorities, compared to white men. For Asians, it’s about 1.8 percent in both models. For underrepresented minorities, it’s 1-1.2 percent, depending on the model. Digging deeper into the data reveals some gaps that are larger for certain groups in certain disciplines.

Without any controls, the gap for women is about 15.8 percent. For Asians, it’s 10.8 percent and for underrepresented minorities, it’s 12.1 percent. Most experts say that some controls are needed because senior ranks of the faculty -- where salaries are typically higher -- still might reflect the bias that limited the ability of those who were not white men to advance in academic careers a generation ago. Further, some of the disciplines that have seen more women hired and promoted nationally are fields (such as the humanities) that tend to pay less than some male-dominated fields in the sciences.

While the gaps suggested in the controlled models are relatively small, the report puts them into context, saying that for women it’s equal to one to four years of experience. The difference for minorities is about one to two years’ experience. In actual dollars, that’s approximately $2,150-$6,092 less for women compared to white men in annual pay and about $2,709-$2,846 less for minorities, compared to white men.

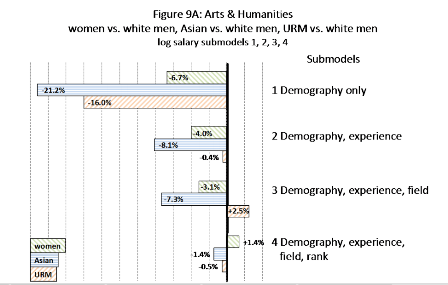

Results differ greatly across schools, divisions and colleges within Berkeley. In the arts and humanities, women actually earn more than white men -- about 1.4 percent more -- when controlling for rank. But not controlling for rank, women earn 3.1 percent less than white men. Controlling for rank, Asians earn 1.4 percent less than white men; not controlling for rank, they earn 7.3 percent less. Underrepresented minorities earn 0.5 percent less controlling for rank, and 2.5 percent more not controlling for rank.

In the social sciences, women earn 1.8 percent less than white men, controlling for rank, and 3.1 percent less considering just experience and field. Differences in salary between Asian and underrepresented minority professors reemerge, with Asians earning 5.4 percent less than white men, controlling for rank, and 2.7 percent less, not controlling for rank. Underrepresented minorities earn 2 percent less than white men when controlling for rank and 4.9 percent less in the less-adjuncts model controlling for just experience and field. (In the baseline models looking only at demography and experience, women fare poorly, earning 16 percent less, with minority faculty members not far behind; the committee attributes this to the economics department, which is less demographically diverse and better compensated than others in the division.)

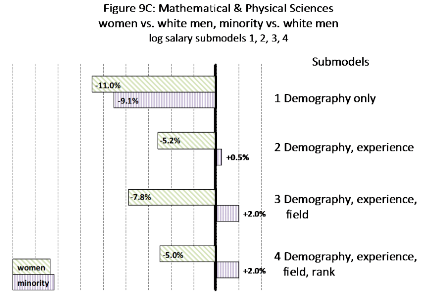

In the biological sciences, women earn 2.9 percent less than white men, controlling for rank, and 5 percent less not controlling for rank. Minorities, meanwhile, earn 3.5 percent more, controlling for rank, and 2.4 percent more not controlling for rank. The differences are bigger for women in the mathematical and physical sciences. They earn 5 percent less controlling for rank and 7.8 percent less not controlling for rank. But minorities earn 2 percent more than white men in both models in those fields. In chemistry, women earn 2.1 percent less adjusted for rank and 10.6 percent less not adjusted for rank. Minorities fare well, earning 5.9-7.9 percent more than white male colleagues, depending on the model. (The report attributes that “volatility” to the program’s relatively small numbers. David Wemmer, department chair, agreed, saying the “statistics of small numbers” probably inflated the impact of having several good, well-compensated professors who happen to be ethnic minorities in a department of about 46 full-time faculty members overall -- what he said was somewhat above average in size in the sciences.)

Both women and minorities earn significantly less than white men in both models in the natural resources fields: 7.4 percent and 4.6 percent less, respectively, in the more forgiving model. Engineering appears to be the most equitable STEM field overall, with modest, positive differences for women (1.7 percent) and Asians (0.7 percent) in the rank-controlled model; underrepresented minorities saw a negative 1.1 percent difference in pay from white men. The reports notes year-to-year volatility in these figures, however, likely due to the relatively small number of faculty members -- just 15 -- in the program.

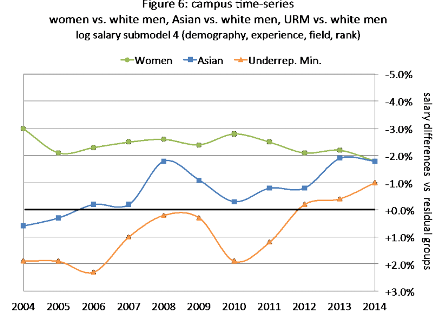

The pay gap for women across Berkeley has decreased since 2004, from 3 percent less controlling for experience, field and rank to 1.8 percent in 2014. But the gap for minorities has widened, from a positive difference of about 0.5 percent for Asians in 2004 to negative difference of about 1.7 percent and from a positive difference of 2 percent for underrepresented minorities in 2004 to a negative difference of 1 percent in 2014. The study again attributes the year-to-year “volatility” in minority faculty members’ salaries to their relatively small numbers on campus.

The committee that did the study says it can’t determine from data alone what’s causing the pay gaps. But committee members committee members..****OK----CF. offer possible contributing causes, such as time in rank, implicit associations or unconscious biases in the faculty review process, social factors that might affect access to education and external factors such as the academic job market and retention. The report includes an exploratory subanalysis on women in the following fields, controlling for scholarly citations: molecular and cell biology, sociology, psychology and business. It found that controlling for Google Scholar citations reduced or eliminated pay gaps between women and white men (the analysis did not include minorities, as the committee determined the sample size would be too small to return valuable results).

The committee says this suggests Berkeley salaries are associated with how often a scholar’s work is cited, and that women’s work may be less often cited than men’s. A similar subanalysis of retention rates found that controlling for whether or not a professor ever has been a “retention case” -- meaning he or she sought a raise in light of a better offer from another institution -- added to the pay gap. Although many women faculty advocates say this plays a crucial role in keeping women’s pay relatively lower, since they are more likely to be geographically bound to an institution due to family responsibilities, the committee says the data set is too small to make a definitive conclusion. But it calls for further study of the issue.

Based on the data and its discussion of possible causes, the committee recommends several steps Berkeley should take to close faculty pay gaps. They include further study, taking steps to help faculty members with work-life balance and improving the campus climate regarding gender and race. The report also recommends faculty salary review programs and salary increases open to all professors but with additional opportunities to help Berkeley meet its “broadest equity goals.” It calls for an immediate review of faculty salary “outliers,” to make sure they’ve been compensated fairly based on their performance.

It also recommends taking a second look at a “target decoupling” initiative adopted in 2012, which aimed to bring the top-performing faculty salaries back in line with the market rate -- but which might have neglected the internal pay gaps issues addressed in the most recent study. The committee calls for a new, three-year faculty equity initiative to be designed by administrators and faculty members by the end of this semester. The report says the program guidelines should "provide mechanisms to ensure that all eligible women and ethnic minority group members are appropriately identified for consideration."

“The steering committee urges in the strongest terms that this study not be put on the shelf,” the report reads. “It should mark the beginning of a new era of thoughtful engagement with issues of faculty salary equity at Berkeley, and it should serve as a basis for fostering sustained and collective discussion and action.”

The Berkeley study is a follow-up to a less comprehensive University of California System-wide study of faculty salary equity completed in 2011. But it also arose from on-campus concerns about gender equity expressed by some professors, which also were documented in a 2011 campus climate survey.

While 1-4.3 percent gaps in faculty salaries might seem small to some, Broughton said she thought such differences “ought to matter. They can be financially significant for individual faculty members as they add up over a career.”

Mary Ann Mason, a professor of law at Berkeley and coauthor of the influential Do Babies Matter? Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower book and larger body of the research of the same name on gender issues and academic careers, agreed, saying the losses are “progressive” over a lifetime. Women professors also end up with one-third less money in their pensions upon retirement, she said. “So yes, it does significantly affect salary in the long run.” (The committee in its recommendations cites Mason’s work, saying Berkeley needs to keep adopting the family-friendly policies she recommends.)

Mason said her research suggests something the study hints at -- that women professors aren’t negotiating their salaries well enough upon hire, putting them at a disadvantage from the start. (Indeed, many experts suggested gender bias was at play in a now-notorious negotiation attempt by a woman candidate at Nazareth College; the offer was revoked.) While men tend to feel comfortable asking for more than they’re initially offered, she said, women tend to say, “Thank you for hiring me.”

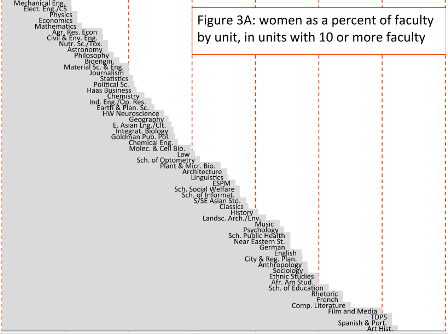

Robert Hironimus-Wendt, a professor of sociology at Western Illinois University who studies pay gaps in higher education, said Berkeley’s study applied a solid methodology, producing findings in line with national data. He attributed the discrepancies to a kind of “gated communities” phenomenon in which programs or departments with the highest pay premiums -- business being a classic example (and in which women at Berkeley lag behind white men by 6.4 percent in pay in the rank-controlled model, and minorities, by 0.2 percent) -- are “really good at hiring people who are like them.” Women make up 31 percent of the tenure-line faculty at Berkeley but in business, for example, are just over one-fifth of the faculty. Berkeley's data on the faculty makeup of programs by gender -- showing that some departments are just 10 percent women and others, more than 60 percent -- further support that hypothesis, to a certain degree.

So in addition to all of the committee’s recommendations, Hironimus-Wendt said he thought affirmative action hiring practices also are necessary to ensure results. “Departments might say, ‘There aren’t any women,’ but if you look at the data, there are,” he said. The professor rejected the idea that departments with the least diversity and the biggest pay gaps will become more diverse in a generation, saying that women have been getting Ph.D.s at roughly the same rates as they do today for 20 years -- already one faculty life cycle. “People want to overcompensate and throw in another variable and explain away the possibility of discrimination,” but it's a perpetual problem, he said.

Broughton said that beyond trying to right faculty pay gaps, Berkeley wants to keep chipping away at the question of why they exist -- important in creating a positive climate for faculty.

“Do the differences reflect group differences in access to important social networks?” she asked. “Do they reflect the operation of implicit association in the assessment of individual faculty members’ records? Do they reflect differences for group members in work-family balance? Questions like these point us toward ways in which we can try to make direct or indirect institutional responses.”