You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When they are being pounded for having raised their students' tuition, public college leaders are quick in turn to point the finger at legislators and governors in their states, whose cuts in financing for higher education are overwhelmingly responsible for the tuition increases.

A new report from the Center for American Progress details -- on a state-by-state basis -- the extent to which recession-driven reductions in public college financing since 2008 have sent tuitions soaring, and how disproportionately low- and middle-income students and the institutions that serve them have been affected.

And the report cites that evidence in arguing for a new partnership in which the federal government would -- with investments of its own -- encourage states to spend more of their own funds to boost college-going and graduation, particularly by those traditionally underserved by higher education.

"Since the Great Recession, states have withdrawn public investment in higher education, and many students from low- and middle-income families have been pushed out of public colleges and universities," says the report, "A Great Recession, a Great Retreat."

"To ensure that American postsecondary education remains affordable for the next generation of students, it is time for the federal government to make an investment similar to the ones recommended by the Truman Commission [of 1947], with the same goal of significantly boosting degree attainment."

The new report follows on one from January in which the Center for American Progress first sought to document the extent of state disinvestment in higher education and to make the case for a new federal-state partnership. The paper being released today goes further, said David Bergeron, one of its authors and the center's vice president for higher education, by supplementing the first report's national data with a close look at what occurred at the individual state level.

Between 2008 and 2012, 29 of the 50 states decreased their direct funding of public colleges and universities, with seven of them dropping by more than 20 percent in constant dollars. (Three states increased their spending by more than 20 percent.)

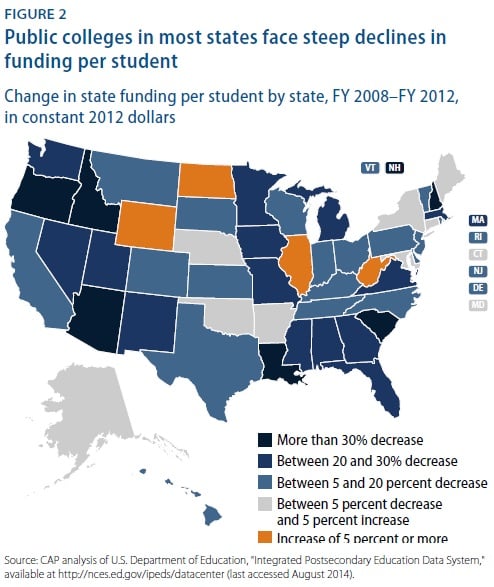

Because public college enrollments grew significantly during this period, the state funding per student dropped more significantly, with declines of more than 20 percent in 20 states and dips of between 5 and 20 percent in 18 others, as seen in the map below.

Public colleges and universities in all but three states, meanwhile, increased the share of revenue derived from tuition dollars, with 10 boosting that share by between 5 and 10 percentage points. By and large, the states that decreased their direct support of higher education the most also increased their reliance on tuition to support their public institutions.

The states' disinvestment has disproportionately hurt less-wealthy students and the colleges and universities that serve more of those students, the report says. In the states that reduced their spending the most from 2008 to 2012, "low-income students pay 18 percent more than the national average at community colleges and 14 percent more than average at public universities;" low-income students pay significantly less than the average in the handful of states that increased their spending on public higher education, meanwhile.

And community colleges were significantly likelier than other public institutions to see their per-student funding drop from 2008 to 2012, the report notes. Of the 45 states that either cut funding or made no change, 31 cut their per-student support for community colleges more than for four-year institutions.

Taken together, the changes in state funding have exacerbated inequality of access to higher education, Bergeron said. "States are not looking after the interests of low-income and disadvantaged populations. This is a troubling trend and one that we put forward this proposal to hope to address."

Just as states tend to cut their spending for higher education when the economy turns down, as the Center for American Progress report shows, they often increase that spending on higher education when the economy rebounds. So won't the situation improve as state economies turn around, as they are beginning to?

Not in ways that will help states enroll and graduate more underrepresented students, as the country needs, Bergeron said.

"We don’t think they will naturally go back to investing in higher education in a manner that promotes equity -- it's important that they reinvest, and not just in their flagships but in their community colleges and public access institutions," he said.

To try to ensure that, the center's paper argues, the federal government needs to give states incentives to enroll and award degrees to students who receive federal Pell Grants or G.I. Bill funds. Under the proposed Public College Quality Compact, the federal government would provide funds to states under a formula that rewards them based on the number of Pell and G.I. Bill recipients who enroll at public colleges and universities, who can afford to pay their college fees without taking out federal or private loans, and who receive degrees from public institutions.

To receive funds under the compact, states would also have to commit to increasing their spending on public higher education (or prove that they had reduced the cost of higher education without diminishing quality), to adopting funding formulas that improved performance and productivity without reducing quality, and to eliminating barriers to educational progress.

Bergeron said the hefty funds needed to pay for the proposed compact -- say $1.5 billion -- could be derived from a set of changes in the tax code that the center estimates could produce $1.5 trillion in new federal revenue.

The new investment would be worth it, he said, because the increased degree production would produce many times more than that in new state revenue.