You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON -- Measuring the job-market returns of college credentials is complex work, according to researchers who gathered here this week for a meeting on higher education data. That makes it challenging, or even risky, for policy makers to use those metrics to hold colleges accountable.

One reason is that earnings data could penalize institutions with a heavy focus on the liberal arts, teacher training or other relatively low-wage fields. Colleges might also shy away from enrolling students who are from lower-income backgrounds and less academically prepared.

Linking government funding with wage-based student outcomes “directly conflicts with an open-access mission,” said David Deming, an associate professor of education at Harvard University’s graduate school of education. “We really need to think hard about getting this risk adjustment right.”

Deming was speaking at the meeting hosted by the Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment, which conducts research in five states and receives funding from the U.S. Department of Education.

Labor-market data was a major topic of discussion at the conference, in part because former students’ wages actually can be tracked, albeit with difficulty. It's at least easier to measure earnings than what students learn in college. And most people agree that it does matter whether graduates of an academic program can get a job with a decent wage, especially if they're taking on significant debt.

One session included new and promising data about short-term certificates that community colleges issue. The panel discussion also provided fodder for the argument that simple performance-based funding metrics based on wages might not be practical, and sometimes conflict with the national college completion push.

The research from the center focused on certificates for programs that took one year or less to complete. Some have suggested that short-term certificates hold little value in the job market, although recent research has contradicted that notion.

The forthcoming study by Di Xu and Madeline Trimble, both of whom are researchers at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College, measured the wages of former students who earned short-term certificates from community colleges in Virginia and North Carolina.

“We see positive, significant returns,” said Trimble.

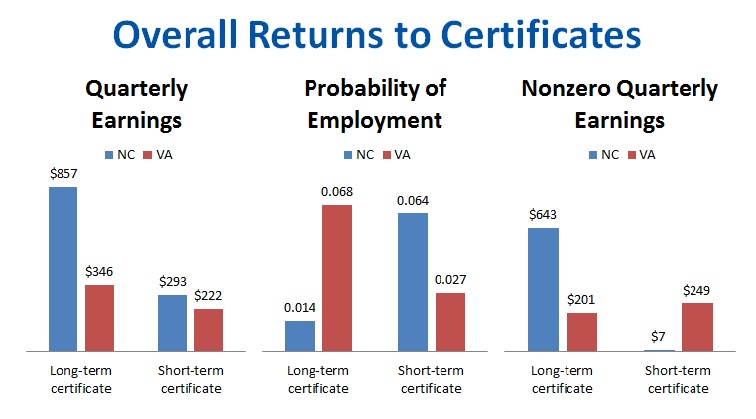

The researchers found both an earnings bump and a higher likelihood of employment for short-term certificate holders. For example, students in North Carolina earned an average of $1,172 more per year with a certificate of one year or less. They were 7 percent more likely to have a job. Those numbers were $888 and 3 percent for certificate holders in Virginia.

Variation and Relevance

Short-term certificates are growing in popularity. They accounted for 38 percent of the credentials community colleges issue nationwide in 2011, Trimble said, and 46 percent of those awarded by two-year colleges in North Carolina.

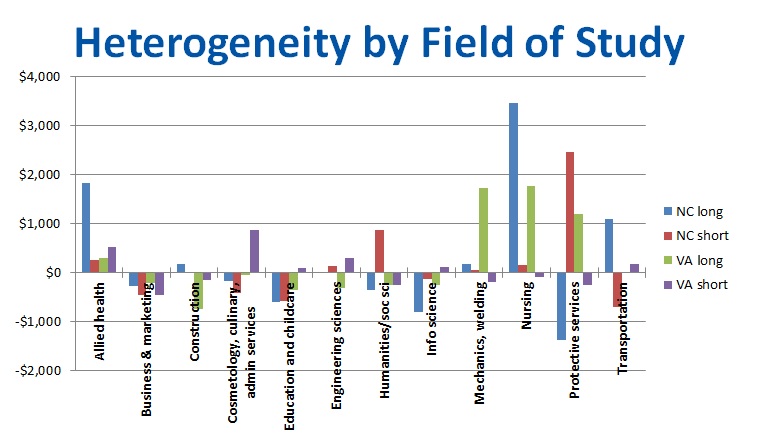

Some of the certificates pay off more than others, even within a single discipline.

For example, Trimble said a basic law enforcement certificate that North Carolina community colleges offer leads to an average annual wage increase of more than $10,000. But that’s because the certificate is “tightly tied to licensing requirements” in the state, she said.

Short-term certificates in nursing or medical assisting failed to yield almost any labor-market returns, the research found, while longer-term certificates in those fields did well. And short-term certificates in some health-care disciplines, such as in phlebotomy in North Carolina or dental assisting in Virginia, did result in substantial wage gains.

Bob Templin, president of Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA), spoke on the panel. He said certificates at his college are designed to be stackable, meaning that the credits student earn for a short-term certificate will count toward further certificates and associate degrees within a discipline. They should also align with bachelor’s and graduate programs at Virginia’s public universities.

Some short-term certificates at NOVA would look good on an earnings-based funding formula, said Templin. Others not so much, and often for misleading reasons.

For example, he said a 12-week certificate in various automotive technology fields, such as one for an emissions specialist, typically leads to employment and an annual wage of roughly $39,000 for students 18 months after they leave college. Yet emergency medical certificates rarely lead to earnings because most students earn them in order to become volunteer first responders for fire departments.

As a result, Templin said labor-market outcomes are “irrelevant” for NOVA’s emergency medical certificate programs.

A similar conundrum applies to the one-year general studies certificates that all Virginia community colleges now issue to students when they reach the mid-point of their way to an associate degree. Those 30-credit certificates are designed to encourage students to complete their degrees.

The certificates are “not about employment at all,” said Templin. “It’s about a momentum point in a student’s trajectory.”