You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The last four U.S. presidents are joining together today to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the AmeriCorps national service program, through which more than 900,000 volunteers have delivered more than 1.2 billion hours of service in thousands of communities.

They’ve tutored at-risk high school students, cleaned up after hurricanes and tornados, and helped build homes for low-income families. They’ve earned more than $2.7 billion from the government to go to college or pay back student loans, according to the Corporation for National and Community Service, which oversees AmeriCorps.

As community work organizers, they mobilize 4 million volunteers a year.

Large numbers -- but they're much smaller than what those involved in founding the national service program under President Clinton had envisioned..

“That is clearly the biggest disappointment,” said Shirley Sagawa, who helped draft the legislation that created the Corporation for National and Community Service and AmeriCorps.

When the Progressive Policy Institute first floated the idea in 1986, supporters dreamed of a $10 billion corps with a million volunteers, said Will Marshall, the institute’s founder.

Today, advocates for the program attribute its limited reach primarily to a lack of federal funding and at-times stiff political opposition. Opponents, generally Republicans, have questioned whether a federal program that offers a monetary incentive to serve is the best way to encourage civic responsibility.

AmeriCorps allows citizens to give a year or two of their time to address some of the nation’s social needs, in exchange for a minimal living allowance and an education stipend – $5,645 per year of completed service.

Advocates say that despite its limited reach, AmeriCorps has still been partially successful in its multifaceted mission to fill the country’s unmet social needs, expand access to college through federal aid in return for service, and build a more civic-minded society.

William Galston, who was involved in starting AmeriCorps as a domestic policy adviser to Bill Clinton, said the program has done a good job with the resources it has.

“The program has survived and thrived in the face of considerable odds,” he said.

Early Ambitions

President Bill Clinton swore in the first class of AmeriCorps volunteers on Sept. 12, 1994, one year after the Corporation for National and Community Service was created.

Clinton had campaigned on the idea of a broad national service program, one that would be widely available to all young people.

But when he got into office, resistance from Republican lawmakers led to a watered-down version of what original supporters of a national service program had wanted, Marshall said.

“It’s growing slowly in that direction, but it would take a long time to get to the point where it’d be a common experience,” Marshall said.

The team that developed AmeriCorps aimed to have 100,000 volunteers within the first two years, Sagawa said.

But 20 years later, with roughly 80,000 spots this year – a number that’s held fairly steady since 2004 – the program still hasn’t hit the 100,000 mark.

The plan passed under Clinton isn’t the only one that hasn’t met desired numbers.

When President George W. Bush was in office, he announced plans to launch the USA Freedom Corps, which urged all Americans commit to volunteering and planned a 200,000-person expansion for AmeriCorps and Senior Corps, a similar service organization aimed at older Americans.

Bush’s push succeeded in increasing the number of AmeriCorps volunteers, but only by about 25,000. (Bush will participate today, though he won't be at the White House in person.)

And then in 2009, President Obama signed into law the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, named for the Massachusetts senator who advocated vigorously for the program until his death. The act called for increasing the number of AmeriCorps spots to 250,000 by 2017.

“And we’re nowhere near that,” Sagawa said. “The scale just isn’t there.”

The limited growth isn’t for lack of interest, advocates say. Each year, there are about five applications for each available AmeriCorps position, according to the Corporation for National and Community Service.

But Congress has not appropriated the funding the agency would need to increase its numbers.

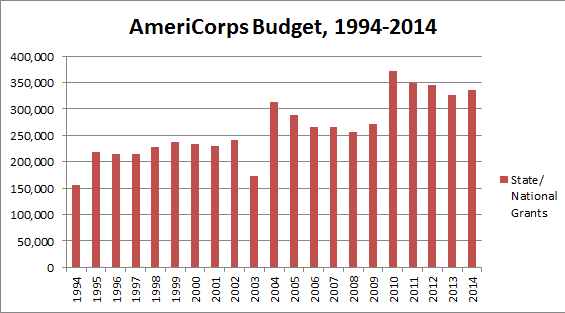

This year, the AmeriCorps state and national program has a budget of about $335 million, roughly the same as it’s been for the past few years. Allocations have fluctuated from a starting point of $150 million in 1994 to a federal stimulus-fueled high point of about $375,000 in 2010.

“As long as there’s a backlog, a waitlist for national service programs, there’s demand,” Marshall said. “Young people want to serve. They want to give back.”

That should be a sign to the White House and to Congress to find ways to bring the project up to scale, he said.

Yet even those who support the idea of national service and applaud some of AmeriCorps’s work question whether the program needs more money.

In an Indiana Public Media broadcast this week, Leslie Lenkowsky, who was the chairman of the Corporation for National and Community Service from 2001 to 2003, said AmeriCorps has a worthwhile goal, and does succeed in teaching participants what it means to be good citizens.

But AmeriCorps isn’t the only option for service, said Lenkowsky, who’s now a professor of public affairs and philanthropy at Indiana University. And several lawmakers would rather see money devoted to other government and nonprofit groups that address some of the same issues as AmeriCorps, but with a more experienced work force.

Other conservatives have questioned whether a federal program has to potential to influence the activities of civic groups and how effective AmeriCorps’ programs are for the amount of money the government spends on it.

AmeriCorps’s Accomplishments?

In 2005, Marshall co-edited a publication with Marc Porter MaGee looking at whether AmeriCorps had lived up to its legacy during its first decade of existence.

What they found, in analyzing the related researched, was a mixed bag.

Research from the 1990s, while limited, did suggest that AmeriCorps was tackling community needs that were previously unmet by either the private market or the public sector, according to the book.

Research from that time also found that AmeriCorps volunteers had an enhanced sense of civic duty and stronger connections to their communities, but that the program hadn’t succeeded in expanding access to higher education, as studies didn’t show an increase in the number of students going to college.

“This experiment in national service has exceeded expectations in some respects, fallen short in others; in a few areas, we still do not have enough evidence to make a judgment,” the book states.

To some extent, that may still be true today, a decade later, Marshall said.

For one, different people have different versions of the goals and roles of national services, and so how its various strands and programs are evaluated will also differ.

Marshall isn’t aware of more recent comprehensive study on the topic. But even without empirical evidence, he thinks most community members who’ve interacted with AmeriCorps volunteers would agree they’re doing quality work.

For Sagawa, the most important accomplishment of the program is that it’s proven the idea that national service can help solve important problems.

Take City Year, for example. Studies have shown the program, supported partially through AmeriCorps volunteers, is making strides in reducing urban dropout rates, said Sagawa who wrote a book titled “The American Way to Change: How National Service and Volunteers are Transforming America.”

There are a lot of examples of similar effective programs, including Habitat for Humanity and early reading programs, she said.

“If you need many pairs of hands, this is a great way to get them,” she said.

None of people interviewed for this article expected AmeriCorps to see any major growth in coming years.

But with 900,000 alumni spread around the country, there’s no denying that the program is slowly becoming a part of the fabric of some communities, said Susan Stroud, founder and executive director of Innovations in Civic Participation. She was also involved in AmeriCorps in its early days.

“The more deeply it becomes embedded in communities, the harder it will be to eliminate it,” she said.

In lieu of financial support from Congress, Stroud and Sagawa said AmeriCorps will have to rely on creative partnerships to continue to grow, as it has by recently teaming up with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Department of Education with its School Turnaround Program.

Colleges and universities could also play a role, advocates say, by ramping up the number of colleges that offer matching scholarships or other incentives to AmeriCorps alumni and researching whether universities could offer credit for service learning during AmeriCorps.

“I think we ought to be having a really rigorous debate right now about the role that national service can play in higher education, and it making it more accessible to college students,” Sagawa said.