You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The portion of first-time U.S. students who return to college for a second year has dropped 1.2 percentage points since 2009, according to a report that looks like bad news for the national college completion push.

The findings are the latest from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The nonprofit group regularly releases studies based on the Clearinghouse’s data sets, which cover 96 percent of students nationwide.

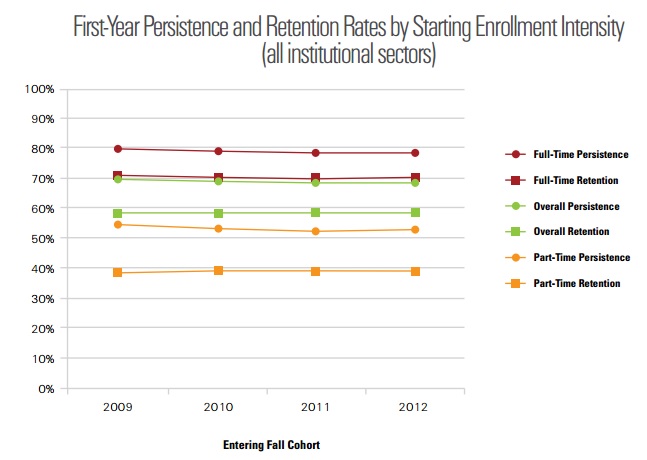

According to the report, which was released today, 68.7 percent of students who first enrolled in the fall of 2012 returned to any U.S. institution the following fall. That number, which is the national “persistence” rate, was down from 69.9 percent for students who enrolled in 2009.

The 1.2 percentage point dip is substantial, as it applies to a total enrollment of 3.1 million students. That means an additional 37,000 students last fall would still be enrolled under the 2009 persistence rate. The largest decline was among young students who were just out of high school.

The biggest drop in the persistence rate among first-time students was at four-year privates, where it fell 2.8 percentage points, followed by four- and two-year publics, which both fell 2.3 percentage points. The persistence rate rose 0.7 percentage points for four-year for-profits.

Improving student retention was a heavy focus during the four-year period the center studied, with increasing attention by policy makers, accreditors and many college leaders.

Dewayne Matthews is vice president of strategy development for the Lumina Foundation, which plays a prominent role in the college completion agenda. He said the center’s findings were both surprising and disappointing.

“It’s a worrisome sign,” said Matthews. “We just added a bunch of people with some college and no degree."

The new report also tracked the national retention rate, which refers to first-time students who return to the same institution after their first year enrolled there. That rate, however, remained virtually the same, holding at 58.2 percent.

Retention rates are lower than persistence rates because some students transfer or enroll at a new college after leaving their first institution. The relative dip in persistence means more students are leaving higher education altogether.

“For each entering cohort year, the overall persistence rate is about 11 percentage points higher than the retention rate,” the report said “Thus, about one in nine students who start college in any fall term transfer to a different institution by the following fall.”

Tough Questions

Lumina has set a goal for 60 percent of adults to hold a degree or certificate by 2025. President Obama has set a similar target.

For several years the foundation has released annual reports on the progress made toward that goal. Gains have been incremental, and the updates depict the hard slog the completion agenda’s proponents face. For example, Lumina last year projected under current trends that 48 percent of adults would hold degrees or certificates by 2025.

Yet the completion push clearly has increased the focus on getting more students to graduation. State lawmakers have taken notice, and are increasingly tying funding for public institutions to performance metrics that include graduation rates.

While Matthews said the new persistence data raise challenging questions, they also add to the urgency around completion.

The report “reinforces the notion that we need to pay close attention to retention,” he said.

The center did not attempt to identify causes for the persistence rate’s decline. But the recovering economy is a likely culprit, experts said. The time period covered tracks along with the economy’s gradual improvement after the last recession. Some students likely are leaving college for jobs and not coming back.

Unemployment rates have dropped by 4 percentage points since 2009, said Jason DeWitt, the center’s research manager.

He said students may be “opting for a short-term employment option” rather than college. The problem with that choice, DeWitt said, is it “can leave them underemployed in the long run.”

That’s because non-persisting students have joined the 36 million Americans -- or roughly 1 in 5 of working age -- who hold some college credits but no degree, according to Lumina.

For-Profits' Gains

The new report breaks out data across sectors of higher education. For-profits were the only segment to see a gain in their persistence rates.

The biggest drop was at four-year private institutions, where the persistence rate for first-time students fell 2.8 percentage points. The rate declined by 2.3 percentage points at both four-year public institutions and at community colleges. Four-year for-profits saw a slight improvement of 0.7 percent.

As with the overall rate, the report does not include possible reasons for the gains at for-profits. The sector saw significant enrollment declines during the time period, however, which could be a factor.

Noah Black, spokesman for the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, the industry’s primary trade group, said for-profits have invested heavily in boosting graduation rates.

“Our sector’s focus on retention and graduation is showing here,” he said. “They had the right support structures in place.”

Across all of higher education, traditional-age students fared worse on the new persistence numbers. First-time students under the age of 20 saw their rate fall by 1.8 percentage points, the study found. The 20-24 age group’s rate dipped by 0.6 percentage points, while students over 24 had a 1.4 percent decline.

It’s unclear why persistence is falling fastest for the youngest students.

Not surprisingly, part-time students have lower retention and persistence rates than their full-time peers, according to the report. But both groups had a drop in persistence since 2009.

“Getting past the first year, either by staying put or by transferring to another institution, is one of the most important milestones to a college degree,” said Doug Shapiro, the center’s executive research director, in a written statement. “We need to find better solutions for keeping students on track to graduation, whether that means the student transfers or stays put.”