You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

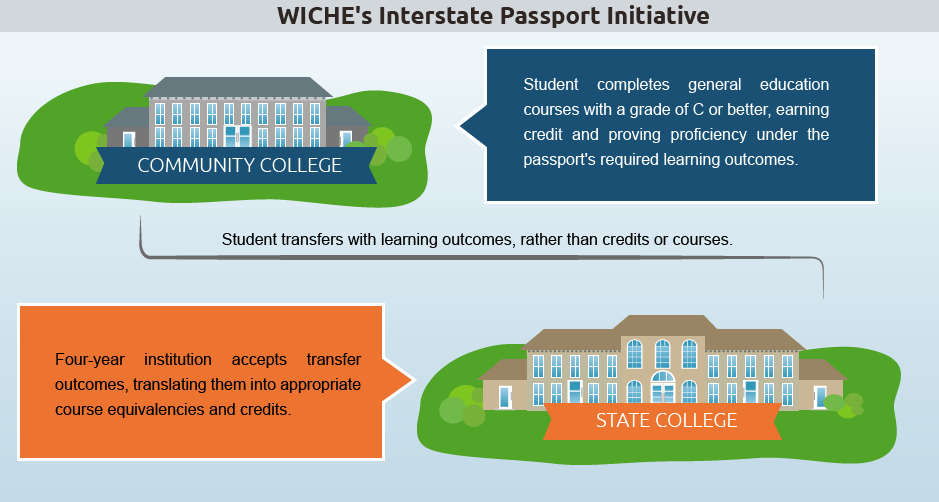

A group of 16 public institutions in four Western states have agreed to a transfer agreement based on what students know rather than on the courses they have taken or the credits they have earned.

The Interstate Passport Initiative, which the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) unveiled this week, is a set of mutually agreed-upon learning outcomes for lower division courses in the general education core.

Students can now transfer from one participating institution to another – even across state lines – and bring their outcomes, or competencies, with them.

Colleges on either side of the process determine which courses and credits equate with proficiency in the learning objectives. And the receiving institution gets to decide which credits a transfer student should earn for his or her proven proficiency (see box below for a list of participating institutions).

“Some institutions may require two or more courses to meet a single outcome while another institution may only require one course,” according to WICHE’s website description of the project, “but each institution will understand the composition of the block at every other institution.”

Beyond its potential impact at participating colleges, the project is important for what it signals about transfer and the credit hour.

Higher education’s central currency for more than a century has been credits earned for specific courses. But the passport, which was created by dozens of academics with plenty of input from registrars and other technical experts, goes beyond the credit hour with a framework of required learning concepts.

As a result, the passport could contribute to the “unbundling” of higher education, where assessed learning typically trumps time spent in the traditional classroom.

“If this works, it could open the door to prior-learning assessment,” said Susan Albertine, vice president of diversity, equity and student success at the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Related approaches, such as competency-based education or digital badges, could also get a boost.

The main impetus for the passport is to create a more efficient transfer process. Many transfer students – particularly those who move from community colleges to four-year institutions – spend time and money retaking courses after transferring.

For example, the average transfer student takes more than a year longer than non-transfer students to earn a bachelor’s degree, spending an extra $9,000 in the process, according to federal data. While some states have worked on this issue within their own borders, WICHE's regional approach could help the 27 percent of transfer students who cross state lines.

“We simply must streamline the transfer process for students. And we must do so in a way that ensures the quality and integrity of the degrees we ultimately provide,” said David Longanecker, WICHE’s president, in a written statement. “The passport achieves this by guaranteeing both the value of the credits received and the competencies developed by students.”

'Revolutionary' Effort?

The pilot project is fairly limited. The three learning areas it focuses on are oral communication, written communication and quantitative literacy. The agreed-upon outcomes in each area can translate into course equivalencies in mathematics, English, writing and communications.

As a result, the passport’s competencies cover a relatively small slice of a typical undergraduate degree’s general education requirement. But the project’s leaders want to add outcomes for other disciplines.

“The hope is that we will be able to build it out,” said Albertine. She said the ultimate goal is a complete, transferable general education core based solely on learning outcomes.

A $550,000 grant from the Carnegie Corporate of New York has paid for the project so far. WICHE is currently looking for a funder to continue supporting the work.

Participating institutions

Hawaii

Leeward Community College

University of Hawaii West Oahu

North Dakota

Lake Region State College

North Dakota State University

North Dakota State College of Science

Valley City State University

Oregon

Blue Mountain Community College

Eastern Oregon University

Utah

Dixie State College of Utah

Salt Lake Community College

Snow College

Southern Utah University

The University of Utah

Utah State University

Utah Valley University

Weber State University

“In the second phase we’ll tackle the sciences, critical thinking and the humanities,” said Patricia Shea, the project’s director, who also directs WICHE’s alliance of community college leaders.

Academics and administrators from California have been heavily involved in the project, but have not yet signed on to the passport.

Ken O’Donnell, associate dean for academic programs and policy for the California State University System, said the system plans to ramp up its participation in the effort. Given the massive scope of Cal State and California’s community colleges, a focus on competencies for transfer in the state would be a major development.

The project’s leaders hope many more colleges and state higher education systems will participate.

“We want to do it and we’re confident that we can,” said Albertine, who has been involved in the work, which draws heavily from her association’s Liberal Education and America’s Promise (LEAP) project. The passport’s three main learning outcomes came from the LEAP project. It also has similarities with the Lumina Foundation's Degree Qualifications Profile and the Tuning project.

By creating the passport, Albertine said, “We thought we were doing something revolutionary.”

Demonstrated Proficiency

The project began quietly more than three years ago. A group of college provosts first hatched the idea to create transfer pathways based on students’ competencies.

While trendy, academic programs based on competencies are not new. Neither is the concept of “block” transfers. Colleges have long matched up groupings of courses – checking boxes for general education requirements – as part of their transfer articulation agreements.

This approach is different, however, because the common currency is learning outcomes, not courses.

“If you’re all working on the same outcomes,” said Albertine, “you can go in all sorts of different directions and still get there.”

Trust is important for this novel form of transfer to work, according to the project’s leaders. It also requires a tremendous amount of technical know-how, experts said, which is why the tech-savvy WICHE made sense as a host for the work.

O’Donnell said colleges have developed myriad administrative systems that rely on the credit hour, including registrars’ offices and IT platforms. So shifting transfer criteria to learning outcomes isn’t easy.

“That whole machine needs to turn,” he said.

The passport is backed by detailed information describing what, exactly, are the agreed-upon transfer-level proficiency criteria for the outcomes. That can be trickier than just matching up two similar courses at different colleges. Faculty members at participating institutions worked together to develop the criteria.

The passport agreement does not require specific forms of assessment. Institutions make the call on how best to determine whether a student is proficient. But a student must be deemed proficient in each outcome to earn successful transfer status in one of the three overarching learning areas -- oral communication, written communication and quantitative literacy.

For example, there are six learning outcome features under the passport’s definition of quantitative literacy: computational skills, communication of quantitative arguments, analysis of quantitative arguments, formulation of quantitative arguments, mathematical process and quantitative models.

The definition of mathematical process (to choose one) is for a student to be able to “design and follow a multi-step mathematical process through to a logical conclusion and critically evaluate the reasonableness of the result.”

That outcome is also undergirded by a description of the various ways a student can demonstrate transfer-level proficiency. For example, she can successfully use “synthetic division, factoring, graphing and other related techniques to find all the (real) zeroes of a suitable cubic/quartic polynomial.”

Sounds simple, right?

However, students don’t need to master every specific proficiency criterion. The passport’s criteria are examples of the “behaviors that a student will display when she has attained adequate proficiency to succeed in her academic endeavors after transferring to another passport institution,” according to WICHE’s website.

The next step is transfer. Say the student earned her proficiency at Utah’s Salt Lake Community College by receiving a grade of “C” or better in math 1040, which is statistics. She could then use the passport to transfer to the University of Utah and earn credit from the university for math 1030, which is quantitative literacy.

Participating institutions plan to do plenty of heavy lifting to track how the passport shakes out. They will collect data about transfer students in the pilot project and plan to send that information to the National Student Clearinghouse. (Utah State University is serving as the passport's central data repository for now.) This will allow colleges to test how the students who received credit under the passport performed in subsequent courses, and to compare their performance to other students.

Several experts involved in the work think the approach to transfer has the potential for much wider adoption.

College transcripts are woefully inadequate at depicting student learning, said O’Connell, citing a widely held belief. He said the passport, however, is a “way of organizing what students know instead of what we told them.”

Many forces are pushing higher education to a more outcomes-based approach. As a result, O’Connell said the broader use of proficiencies for transfer credit is not only feasible, but “in a sense inevitable.”