You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

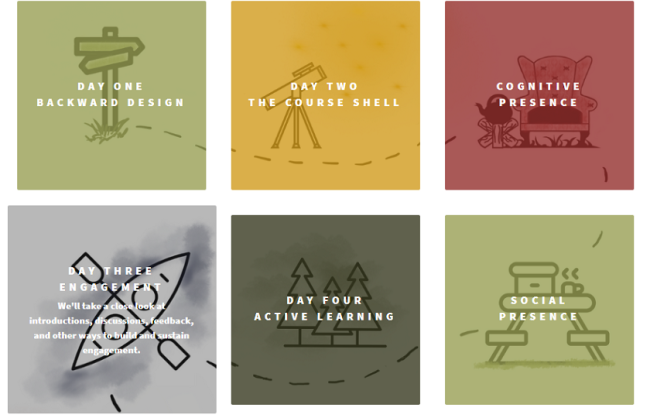

Camp Design Online screenshot

Muhlenberg College

Welcome to "Transforming Teaching and Learning," a column that explores how colleges and professors are reimagining how they teach and how students learn. If you'd like to receive the free "Transforming Teaching and Learning" newsletter, please sign up here.

***

Most professors became learners themselves this spring. Forced by COVID-19 to make their in-person courses available to suddenly dispersed students, instructors had a matter of mere days to figure out how to deliver their curricula and connect with students from a distance, using technology tools many had never used before.

They got help from their fellow instructors and from their institutions’ teaching and learning centers and instructional technologists, who worked overtime to smooth the transition. They turned to more digitally experienced peers at their own colleges and elsewhere, and they sought advice from their colleges’ technology partners, from new crowdsourced resource lists and from experts sharing their tips in Inside Higher Ed and elsewhere.

Two things were heartening about that phenomenon. First was the willingness of so many instructors to acknowledge that they needed help and to seek it out. As Jessamyn Neuhaus of SUNY Plattsburgh described it in this column two weeks ago, "For the first time, it was acceptable, even desirable, for smarty-pants experts to say, 'I need some assistance; I’m not sure how to teach this right now.' It became culturally acceptable for people to just admit, 'I’m not totally sure how to do this.'"

That isn’t the behavior of a group of people who don’t care about teaching or whether their students learn, as critics often assert about higher education faculty members.

The other noteworthy aspect of the sharing economy around improving teaching this spring was how willing individuals and institutions were to share their wisdom and their ideas with others. Some of it might have been self-interested, like the technology companies that made their products freely available temporarily because of the pandemic.

But much of it is consistent with the communities that have emerged over the last decade around open educational resources and digital pedagogy, in which curricular materials and teaching practices are freely shared, with the goal of trying to raise the bar for learning broadly.

“Those communities are built on the premise that we’re not in competition with each other, that we’re stronger together,” says Lora Taub, dean for digital learning and professor of media and communication at Muhlenberg College, in Pennsylvania. “And this moment has proven that to be true: we see campuses and working groups sharing out resources on a very small scale to a very large scale.”

Now colleges and professors are preparing for a fall like no other. Whether they are currently planning for instruction to be mostly on campus or mostly virtual, most are working to ensure that courses can be delivered to students face-to-face or online, given the reality that at least some students and some instructors will choose or be forced to remain remote.

In response, several new initiatives are emerging to help individuals and institutions continue to navigate this terrain. Some of them are explored below, and I encourage you to share others in the comments section or directly with me.

***

Taub, of Muhlenberg, says her institution has benefited enormously from previous efforts by other institutions to share their wisdom and resources, such as the open source "Domain of One's Own" project out of the University of Mary Washington that allowed for the creation of personal webpages for instructors and students.

So when Muhlenberg tasked Taub and her colleagues to provide faculty development this summer to prepare every one of the college's 320 full-time and part-time faculty members to teach both in person and online this fall, "we committed to doing it in a way that could be shared openly" beyond Muhlenberg.

Cue Camp Design Online, "an intensive, peer-supported learning community for bringing courses online." The course, which was built using a Creative Commons license that allows others to use and build off it, was reimagined from the semester-long faculty development program that Muhlenberg has offered every spring since 2015, usually to cohorts of a dozen or fewer faculty members. (A total of 40 instructors had completed it before this spring.)

To meet the charge of preparing hundreds of instructors, Taub and her Muhlenberg colleagues, including Jenna Azar, a senior instructional design consultant, refashioned the semester-long course into two nonconsecutive weeks. Participants spend the first week undertaking a curriculum on effective practices in building courses, during which they engage in discussion boards, Zoom calls and other activities within the Canvas learning management system the college uses. "Faculty turn toward each other to share their experiences last spring, what they found worked, what they want to carry forward this fall and what they struggled with. That discussion space for faculty to share examples, experiences and approaches is vital," Taub says.

For the next three to four weeks, instructors build their own courses, building off what they learned during the first week's curriculum. After that, they return for a second, "peer-driven" week, in which they "share what they've been building, practicing, working on," says Taub. "At the end of the second week, they should emerge with something solid that they can move into the uncertainties of fall with." The course should be a "foothold for what remains, still, a fairly uncertain fall semester."

Muhlenberg has not yet announced its plans for the fall term, but Taub notes that "even if we're on campus, there will be students and faculty and staff who remain remote, for health or familial reasons … So we're encouraging them to redesign their courses for a multimodal experience."

The course is a team effort. In addition to the instructional designers and other professional staff members, professors who previously took Muhlenberg's spring faculty development course are serving as faculty fellows, and Azar has a team of student digital learning assistants who are paid to serve as the "central student voice" as faculty members build their courses. "We can't get by just sharing anecdotally what the experience might be for students," says Azar. "They've been really critical partners."

The Centrality of the Liberal Arts Experience

Muhlenberg's commitment to digital and online learning is larger than is typical for liberal arts colleges, and Taub says the college has put its faculty development process "out in the open because we recognize that the very thought of online learning in the liberal arts is anathema to some … We wanted to engage our community and the wider higher education community so that each step of the way, we're engaged in critical conversations about the extent to which our exploration in digital and online learning aligns with our tradition of liberal arts learning."

Taub and Azar don't assume that Muhlenberg's approach to faculty development will necessarily apply to every institution. But so far liberal arts peers such as the College of Wooster, Wesleyan University and Middlebury College have embraced Camp Design Online wholly or partly this summer, and their experiences will in turn help Muhlenberg "hone, revise, improve our model," Taub says.

Like many professionals who've been working for years to help and encourage faculty members to experiment with new ways of teaching, Taub is "energized" by the fact that so many more instructors are doing so now, even if they haven't chosen it.

"Nobody wants to be in the situation we're in now, but nobody wants again to be where we were in the spring, either," she says. "So we have a remarkable opportunity to make visible what we know: that [digital learning] is not by and large a technological endeavor, it’s a human endeavor to which we are accustomed to bringing a great deal of care for students."

"Many faculty experienced a real profound loss of connection with their students in the spring," Taub adds. "That translates to a commitment to craft ways of centering connection and engagement and relationships in the hybrid and online learning we'll have this fall, if necessary. Each of us has had an experience where voices that we don’t often hear in the classroom find space to express themselves online."

With a smile on her face, Taub relays the experience of watching one of Muhlenberg's longest-standing faculty members -- "who has described himself as a technophobe, Luddite" -- join the ranks of instructors who've shown "a remarkable willingness and curiosity" to learn new things.

"I did not expect to get excited about all this; I expected only to learn how to handle a few inadequate, unexciting tools," Alec Marsh, an English professor, wrote to Taub and Azar at the end of Camp Design Online. "Instead, it feels like looking out at a big lake. It'll be fine, more than fine, once I get into that water. Now I'm in about up to my ankles! The water's cold, now, but it'll refresh by and by."

***

Muhlenberg's faculty development course is just one of numerous new initiatives designed to help faculty members and professional staff prepare to remake their approaches to instruction for a highly uncertain and potentially unstable fall term (and beyond). The list below is not meant to be inclusive, so please don't be angry if yours isn't there. Instead, please add your suggestions below, or tell me about them and I'll check them out.

Open-Source Collection From an All-Star Group: West Virginia University Press's Teaching and Learning in Higher Education series, edited by Assumption College's James M. Lang, author of Small Teaching, is among the best collections of instructional expertise around. So it's not surprising that a website developed by the series' authors, released this week, is likely to be enormously valuable, too.

Pedagogies of Care: Open Resources for Student-Centered & Adaptive Strategies in the New Higher Ed Landscape features advice from 16 authors in the WVU Press series on course design, teaching, collaborative practice and assessment, through a mix of videos, presentations, recordings and Google Docs, all under the banner "You Are Not Alone."

Victoria Mondelli, founding director of the Teaching for Learning Center at the University of Missouri at Columbia, drove the creation of the collection by asking the series' authors whether they'd be willing to create a derivative work from their books and license it openly. "I reckoned a collection of educational gems from these particular experts could be a lifeline for not just me and my campus but everyone else, as well," she said via email.

The authors -- who include many leading lights in the teaching and learning world -- responded overwhelmingly, and as the selections poured in, Mondelli said in an interview that she was struck by a "thread" that ran through many of them: "the need to center student well-being." That might have been the case even before the pandemic upended students' worlds, educationally and otherwise, but providing education that is student-centered and adaptive "is going to stick here," says Mondelli, who co-edited the collection with Thomas J. Tobin of the University of Wisconsin at Madison. "I don't think there's any going back."

The time is right for more attention to how professors teach and students learn, she says. Faculty members need and want to improve how they teach in new and unaccustomed venues, and provosts, deans and other administrators are increasingly concerned about how to ensure quality instruction at a time of educational disruption, Mondelli says.

"This is a moment that folks are willing to make really strategic resource allocations to serve faculty," she says. But it's also clear that "all but the wealthiest centers for teaching and learning" may see their budgets constrained as colleges struggle with state funding cuts or enrollment declines, or both.

"This collection has a lot of great stuff in it, and you could fashion a summer institute or a book club approach to keep your faculty stimulated at extremely low cost or no cost," she adds.

A MOOC From Michigan: The concept of resilient pedagogy is getting a ton of attention right now, which makes sense given the moment we're in.

Rebecca Quintana, learning experience design lead at the University of Michigan's Center of Academic Innovation, describes resilient teaching as "the ability to facilitate learning experiences that are designed to be adaptable to fluctuating conditions and disruptions." Her new massive open online course on Coursera, Resilient Teaching Through Times of Crisis and Change, has about 550 faculty members and instructional designers enrolled, and Quintana says she's been "astounded" by the degree of interaction in the course -- "very different from other MOOCs."

"There's almost a cathartic sharing of what the spring was like," she says. The course, which she and Michigan's James DeVaney described in an Inside Higher Ed blog post last month, grounds learners in the principles of resilient design for learning and highlights examples of new courses that have been redesigned to align with the theories.

As is true for Taub and Mondelli, Quintana is hopeful that the tumult and uncertainty faculty members have faced this spring will have a real upside.

"We see a vulnerability among faculty, a willingness to throw open the doors of their classroom, which is not something you’re used to doing," she says of the spring. "We were all thrown off-kilter and did the best we could, but people are more willing to share what worked well and what didn't. It's somewhat freeing and terrifying, too."

Looking toward fall, "people are spending more time than ever thinking about their teaching," she says. "They're investing all kinds of effort, all kinds of attention, and I'm hopeful we can come out even stronger, with course design that could be even more effective for more learners."