You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

UMass president Marty Meehan

UMass

From Massachusetts to California, as many as two dozen state university systems, individual flagship campuses and other public universities are talking publicly (or quietly) about undertaking ambitious online learning initiatives.

Some are focused on enrollment or revenue growth, some on better serving the millions of working adults or other populations of Americans that traditional higher education has historically struggled to reach.

Some aim to join the ranks of regional or even national players like Arizona State, Southern New Hampshire and Western Governors Universities; others strive to retake or hold on to state residents now studying online at institutions elsewhere.

“The time for us to act is now,” Marty Meehan, president of the University of Massachusetts, said in announcing the system’s online plan in a speech last month. “It’s predicted that over the next several years four to five major national players with strong regional footholds will be established. We intend to be one of them.”

Whether they’re thinking big or small, wanting to move fast or slow, in one way or another institutions and states want to move more aggressively into online education than they have heretofore -- raising several key questions:

- How many additional institutions can “go big” online, in some cases overcoming cultural, political and other barriers?

The View From the Ground Level

Please see these related articles:

- Missouri and Louisiana are among the state institutions plotting major online growth.

- Arkansas' freestanding eVersity has grown slowly since 2015.

- Will these striving institutions largely focus on state residents now studying online elsewhere, or try to expand the pool by reaching adults who aren’t enrolled now at all? To the extent they target the latter, how successfully will they be able to transition to educating students they have historically struggled to attract? And can they price their programs low enough to attract those students?

- Will institutions that want to build significant online presences develop new structures and student bodies from scratch, or will a meaningful number of them try to catapult their way to online prominence by imitating Purdue University's purchase of Kaplan University? To the extent they choose a middle path -- using corporate providers to fuel their growth -- will they face significant blowback from politicians, faculty members or others?

Lots of Activity

The list of public colleges and systems plotting their moves into online learning is large and growing. The nature and scope of their initiatives vary widely.

In the last year, the California Community Colleges and University of Massachusetts systems both have announced plans to create new, freestanding institutions to serve working adults. A similar approach is reportedly under discussion within the University of North Carolina system, although those conversations have stalled amid major governance turmoil there.

The University of Missouri system last year signaled plans to expand its total enrollment from 75,000 to 100,000 by 2023, pointing to online education as a key driver of future growth. Louisiana State University brought on a veteran of Southern New Hampshire to lead ambitious online growth in undergraduate programs (hiring expertise, in a way, instead of contracting with an outside provider for it), and the University of Montana plans to forge an online program management partnership with either Pearson and Wiley as part of its online growth efforts, according to the Missoulian. (Read more about these developments in this related article.)

Legislators in Virginia wrote language into 2019 budget legislation that would have created an avenue for George Mason University to take over a for-profit college in much the same way Purdue purchased Kaplan in 2017. The bill passed one house of the Virginia legislature.

This flurry is far from the first major foray of public universities into online education. A cadre of early movers have done so successfully: Arizona State University and the University of Maryland University College are the largest, with exclusively online enrollments of at least 25,000, while others such as Pennsylvania State University’s World Campus, the University of Central Florida and the University of Florida have tens of thousands of students taking at least one course online (many of them also studying in person). Others have moved online more recently, including the University of Arkansas system’s freestanding eVersity. (See related article here.)

But numerous public universities have suffered high-profile failures or false starts in efforts to launch major online operations -- most notably the University of Illinois’s Global Campus, a separate online arm that the California State University System sought to build, and multiple stunted efforts by the University of Texas system.

Economic and enrollment worries are largely driving this round of proposed online expansions. In explaining UMass’s major online plans, system president Meehan spoke both about better serving the one-million-plus adults who are candidates for but not enrolled in postsecondary education and about trying to secure the university system’s financial future amid a pending drop in prospective traditional-age students. UMass leaders have set not an enrollment goal but hope to eventually reach over an unspecified term revenue of $400 million.

The Target Students

Many of the other proposed new initiatives are, like UMass’s, focused on working or nonworking adults, especially in the numerous parts of the country where the number of high school graduates will fall over the next decade. That decision makes sense practically, given demographic projections, and from a policy standpoint, given a widespread need for more skilled employees.

“We’re really focused on high quality, affordability and access to Missouri adult learners who want to advance their careers through further training,” Mun Y. Choi, president of the University of Missouri system, said in one typical description of the target market.

But for many public universities, focusing aggressively on adult learners would represent a major shift in strategy. Adult students have historically enrolled mostly at community colleges and for-profit colleges, and for-profits figured out earlier than other postsecondary institutions that many adults wanted to or could only study online.

At most public universities with modest-size online presences, many if not most students are supplementing their in-person academic programs with the occasional online course.

In taking aim at adult online learners, UMass is typical in sending mixed signals. Meehan and Don Kilburn, the former Pearson Education executive who now heads UMass Online, mentioned the nearly one million adults in the state who lack degrees or need training.

But Meehan also suggested that the system would aim first at defending the state’s border from institutions like the private nonprofit Southern New Hampshire, which enrolls 15,000 Massachusetts residents. “Out-of-state institutions without our same reputation for academic excellence are enrolling adult learners in Massachusetts in the types of programs we seek to offer,” Meehan said.

Data from the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements show that Southern New Hampshire enrolled 63,000 students from the 48 states (excluding Massachusetts and California) that reported to the organization in 2016-17, including roughly 5,300 from Texas, about 4,000 each from Florida and New York, and 3,000 or so from New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Western Governors University, an online-only institution that, like Southern New Hampshire has experienced explosive growth by enrolling adult learners in the last decade, shows similar patterns, though its biggest enrollments are in states where the private nonprofit has set up outposts, such as Indiana (7,242), Texas (10,308) and Washington (14,001).

The president of Western Governors, Scott Pulsipher, has said he believes the institution’s current enrollment (roughly 100,000 as of December 2018) can grow tenfold -- reflecting his view that many more adults will seek a higher education and will do so online.

But recent history hasn’t reflected that. In 2007, the year before the Great Recession began, roughly 7.5 million adults age 25 and older were enrolled in American colleges, according to federal data. By 2011, that number had grown to 8.4 million, but it dipped to 8.1 million in 2015, fell to 7.8 million in 2017, and is projected to grow modestly to 8.3 million in 2020.

Paul LeBlanc, president of Southern New Hampshire, asserts that institutions like SNHU and WGU have “grown more at the expense of” the for-profit colleges whose enrollments collapsed amid regulatory scrutiny and financial failure “than by expanding the pie of adults” enrolled in postsecondary institutions. “We’ve obviously had growth,” he said. “But we’ve [mostly] seen the migration [of students from elsewhere]. We didn’t add to the overall pie.”

UMass and other public universities moving aggressively into the online space would do better -- for themselves and the country -- if they succeed at enrolling students new to higher education, rather than just holding on to the Massachusetts residents now studying online at places like Southern New Hampshire, LeBlanc says (admitting a bit of self-interest).

“We all need to serve more adults, and more opportunity youth, low-income youth,” he says. In addition to its one million adults without a credential, LeBlanc said, Massachusetts “has got something like 700,000 opportunity youth” -- those who’ve graduated from high school but are not enrolled in postsecondary education or participating in the work force.

The Public Universities’ Advantages (and Impediments)

Officials at UMass and other public institutions planning aggressive moves into online education believe they have one big edge at their disposal: their brand.

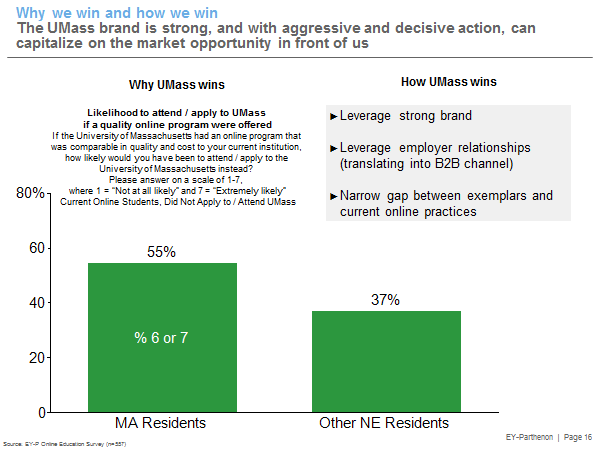

A market analysis prepared for UMass last fall by the consulting firm EY-Parthenon found that 55 percent of Massachusetts residents (and more than a third of other New England residents) who were already studying online elsewhere said they would be very or extremely likely to enroll at UMass instead if it had had a program comparable in price and quality to the one they were in.

“The UMass brand is strong, and with aggressive and decisive actions, can capitalize on the market opportunity in front of us,” the consultant’s report stated.

Trace Urdan, managing director at Tyton Partners, an education-focused investment bank and consulting firm, agreed that state flagship universities and some other public institutions have the potential to attract working adults into online education who might not have previously enrolled at a for-profit college or well-marketed online institution like Western Governors or Southern New Hampshire.

“If you’re a place like UMass and you go toe to toe with SNHU, you should brand beat them, clean their clock,” Urdan said. “That is, if your programs are priced appropriately and you know how to onboard students and do all the things that the existing players do well.”

That’s a big if, Urdan and many other analysts say.

Kasia Lundy, a managing director at EY-Parthenon who worked with UMass, said in an interview that “these public brands will just have stronger draw and recognition.”

“Then the question becomes, can they actually deliver this in a way that is good for the student? Can you get your pricing down to a level that is affordable for students while still providing the quality of supports that these students need to succeed? That’s where things often break down -- many people vastly underestimate what it actually takes to put up the infrastructure and wraparound supports that good online programs require.”

Which gets to the major disadvantage faced by many of the public universities seeking online prominence: their lack of experience dealing with working adults and the other students likeliest to enroll fully or mostly online, many of whom have less experience in higher education and may have more academic risk factors.

LeBlanc cites the failures of online initiatives at the University of Illinois and California State University a decade ago. “It wasn’t their brand that undid them, obviously.” Brand may work locally, within a state, he says, “but not much beyond. The great bulk of working adults make very little distinction between brands, beyond a handful at the very top. After all, we built a national footprint with no brand at all.”

What Southern New Hampshire and WGU and others focus on, LeBlanc said, are “all the under-the-hood process and policy work that has to get done. If you don’t understand what [working adult students] need you to do for them, and you merely port over what you do on the campus, you’re going to fail.”

Evie Cummings, who took over the University of Florida’s UF Online in 2015 after the original vision of creating a statewide online institution from scratch largely collapsed, noted that “public higher education was asleep at the wheel” as first for-profit colleges and then places like WGU and SNHU identified working adults as a group often best served through more flexible forms of learning.

“If our mission as a public land-grant institution is to serve the needs of the state of Florida and the broader mission of higher education, we simply must rethink how we do that. We must have a diverse set of pathways,” Cummings says. “Our students of the future are different from our traditional campus students. They are a much more diverse, mobile, dynamic student population that we have to pivot to serve.”

Recognizing the need to serve that population and being able to do so well aren’t one and the same, says Lundy of EYP.

Allowing students to start programs four to six times a year rather than the traditional two or three times can cause friction with existing registration and financial aid policies; changes in the instructional delivery format can require a different sort of teaching model; and the “whole wraparound infrastructure” can be very different from the types of student services offered to residential 18-year-olds, she says. “We often hear college administrators say, ‘We offer all that.’ It’s not until they dig into leading online practices that they acknowledge that the traditional student service model is not sufficient and requires significant investment to adapt to the needs of the online student.”

Then there’s the price tag. Most public institutions charge as much or more for online programs as they do for in-person programs, although some recent experiments (more at the graduate level) with Coursera and edX are beginning to drive down online pricing ever so slightly.

“Many publics that want to price competitively will have to blast through the usual rules for in-state and out-of-state students," says Urdan of Tyton.

Build, Buy or Something in Between?

The EY-Parthenon proposal for the University of Massachusetts contained a slide called "How do we get there?" noting that "certain paths" to establishing the system's ambitious plan to enroll tens of thousands of online students "are more likely to succeed than others."

The likeliest path, the consultant said, was "acquisition -- buying an existing online university's infrastructure and students." Next was building through the use of third-party providers -- the favored path for many institutions these days, in which outside online program management companies make up-front investments to help universities build programs in exchange (typically) for a large share of revenue over a decade or more.

The option whose success was "not likely"? An internal build, in which course content, student enrollment and "all necessary infrastructure and capabilities" are built organically from within.

Cummings, the leader of Florida's UF Online, makes the strongest argument for an internal build -- perhaps not surprisingly, given the messy collapse of the university's relationship with Pearson in 2015.

She acknowledges that Florida -- which was under intense pressure from the Legislature to build an online strategy within months -- could not "be where we are today" without Pearson. But as someone who believes that "public institutions need to transform themselves" to continue to meet their historical missions of access, equity and excellence, she thinks it would be a mistake for institutions to create freestanding, separate arms to drive their online expansions.

"Serving new groups of students in new ways requires you to transform your service models, change things to give your students and your faculty what they need to be successful," says Cummings, who acknowledges that that work is hard. "Ideally you should make sure it’s fully integrated into your departments and across your institution, and creating a standalone school is putting off the inevitable," she adds.

Similarly, institutions moving aggressively into online education now may "feel they're behind, late," and may -- as UF Online did -- lean heavily on outside providers to move faster. If they do, they should be careful in crafting agreements, she warns: "Make sure they’re time limited, and make sure the agreement can mature as your goals do."

LeBlanc of Southern New Hampshire takes a sharply different view of the integration versus separation question. "Take a look at who has been able to successfully scale online," he says, citing his own institution (where the online operation was purposefully fenced off from the rest of a then-struggling university) as well as UMUC and WGU, both of which were created out of whole cloth. "There is no example where the integrated model has worked for getting any kind of scale. If you have to integrate, you will consume and kill the new thing."

That may be why several of the state systems and universities that are considering major pushes online are contemplating buying an existing online provider or creating a freestanding unit or separate institution to offer online programs, as EY-Parthenon suggested UMass consider.

George Mason sought language in recent budget legislation that would clear the way for the Virginia university to create a public-private partnership to "create or operate" an entity to deliver "distance or technology-based learning." The university was believed to be exploring a possible purchase à la Purdue's of Kaplan, although its officials have stayed mum on the matter.

Most experts on the online learning market seem skeptical that "there will be a lot of Kaplan-Purdue plays," as LeBlanc of Southern New Hampshire put it -- transactions in which public (or private nonprofit, for that matter) universities seek to become a major player essentially overnight by absorbing an existing set of students and a working structure for educating and serving them.

In recent months several institutions believed to be possible targets of such a purchase have been taken off the table: Laureate Education decided not to sell its Walden University, a mostly graduate online university serving tens of thousands of students, and this month Career Education Corp. bought Trident University International (formerly Touro University's online arm) and plans to merge it with its American InterContinental University, a regionally accredited online institution. Ashworth College, a nationally accredited online institution, sold this month to Penn Foster.

Numerous other for-profit institutions could be targets for nonprofit institutions with online ambitions -- American Public University, Grantham University, Columbia Southern University, even the University of Phoenix -- but "I don’t think the number of targets is the constraining factor. I think there’s stuff to buy," said Urdan of Tyton. The bigger impediments, he said, are the political, regulatory and faculty blowback that would likely accompany any such transaction (as it did at Purdue, whose president, Mitch Daniels, seemed to have the political support to withstand the criticism).

At the opposite end of the spectrum is building a new online operation from scratch. While that might elicit less opposition internally, that approach brings its own challenges: requiring significant up-front investment, and typically patience for what in almost every case is going to be a slower ramp-up.

"And there is a question if you miss that window if you do that internal build," said Lundy of EY-Parthenon, which is part of Ernst and Young.

Most experts expect most institutions to choose the in-between course: using online program management companies and other external partners, which is already how increasing numbers of colleges are taking their programs online these days, especially to help them with areas, like marketing, in which they lack expertise.

We won't turn this into another story about the OPM market, about which "Inside Digital Learning" has written a lot in recent years.

But arrangements of the type and scale that state systems are contemplating now -- spanning an entire university (or state system), with dozens and perhaps hundreds of courses and programs of varying sizes -- are not how most of the online program managers are accustomed to operating, Lundy notes.

And the online program management companies have begun receiving (and are preparing for more) scrutiny from regulators and consumer advocates concerned about their financial terms and lack of transparency. "I think there will be more of a light shined on OPMs and institutions, focused on how much of a student's experience is the institution and how much is the OPM," LeBlanc predicts.

The Landscape for Publics Moving Online

We're haven't fully answered the question of how many public universities and state systems will move aggressively online, and how many are likely to succeed -- mostly because they're not answerable at this stage.

What is clear is that numerous places are planning to do so or seriously considering such a move -- and that they have both opportunities and impediments in their paths.

Myk Garn, assistant vice chancellor for new learning models for the University System of Georgia's Board of Regents, says that one of the underrated elements of potential success in online education is leadership.

"One of the key things in this is the executive sponsors," he says, referring to senior leaders who champion an endeavor like a big push online. "It takes a real interesting blend" of aggressiveness and staying power, Garn says. "You can have someone who comes in and tries to do a lot of change really fast but faces blowback. They don't tend to last as long. Or you can have someone who moves incrementally, and it may not be fast enough to stay ahead of or keep up with the competition.

"Then there's the real unique blend of someone who can push and encourage and do it for a number of years, requiring both the right personality and the length of tenure to get the job done."

Cummings of UF Online offers another caution, perhaps better described as a plea.

"I'm a little disappointed to hear all these people talking about doing these online operations with a focus on enrollment goals," she says. "It seems like online is this panacea for enrollment challenges, rather than thinking about how you can harness these digital pathways to fulfill your mission, which for most of us is an inherently local notion."

Cummings says she and her colleagues in Florida prefer to think of online education as a way to "reach our students in new ways -- students who wouldn’t be able to reach higher education in other ways. If that's your call, you don't tend to talk about how you're going to reach X students in Y years.

"It's not like I'm saying, 'Oh, everybody, slow down, don't do anything.' There is an imperative for us to do new things.

"Don’t go slow, just go thoughtfully."