You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Digital learning administrators at the University of Central Florida admit they’ve made some mistakes in recent months -- and they’re taking steps to rectify them.

Students in the College of Business last month stoked a vigorous debate over the most effective classroom models for teaching and learning after the university introduced a new blended and active modality that alienated some students. Tom Cavanagh, the university’s vice provost for digital learning, told “Inside Digital Learning” he thinks he and his colleagues didn’t give students enough compelling reasons to keep an open mind about shifting to learning mostly online, with five active learning classroom sessions per semester.

“Where we probably could have done better is communicating to students why we were doing [the new model], the benefits that would be associated with it, how it would be changed for them based on previous experience of the lecture-capture format,” Cavanagh said. “We probably could have done a better job of change management.”

“Inside Digital Learning” last month highlighted student concerns and administrator responses to the new “reduced class time” format, which includes five in-person sessions for active learning in groups as well as traditional textbook readings and worksheets that students experience online.

Some students said they want more in-class time to engage directly with the professor on material that will appear on their exams, and many students said they wanted more modality options for their core courses, all of which are now offered exclusively in the reduced class time format.

Administrators cited data suggesting that many students rarely if ever attended in-person lectures when they were offered, and remained steadfast in their commitment to seeing how the new model plays out.

Cavanagh said his team is working with business college administrators to offer for some courses more than the standard five in-person class sessions.

The university’s Student Academic Resource Center, along with representatives of the business college and Cavanagh’s team, will also begin offering “just-in-time” support sessions to help students get acquainted to the online learning environment, where the bulk of their learning takes place. Cavanagh calls the new offering, which will be actively marketed to students with grades below a certain threshold, a “combined online and face-to-face co-curricular support curriculum.”

“I sort of feel like we’re on the defensive a little bit,” Cavanagh said. “Some of that may be our own doing.”

Commenters on the “Inside Digital Learning” article raised additional questions about the nature of the university’s model and its viability as a new approach to teaching students. Here are some additional details to fill in your understanding of the situation at UCF and its nationwide implications.

Why did this experiment happen first at the College of Business?

With more than 9,000 students, the business college is the fourth largest of the university’s 13 schools. For more than a decade prior to this semester, it been the only college on campus to offer all of its core courses in the lecture-capture format, in which students can attend class in person or watch streamed lectures live or recorded lectures on their own time. But according to Cavanagh, the lecture-capture format was flawed from the start.

“Having students passively sitting at home watching 75-minute lectures, bingeing them at double speed before the midterms, not coming to campus, is not the kind of educational experience we wanted for our students,” Cavanagh said.

How did data factor into the decision to move forward with “reduced class time”?

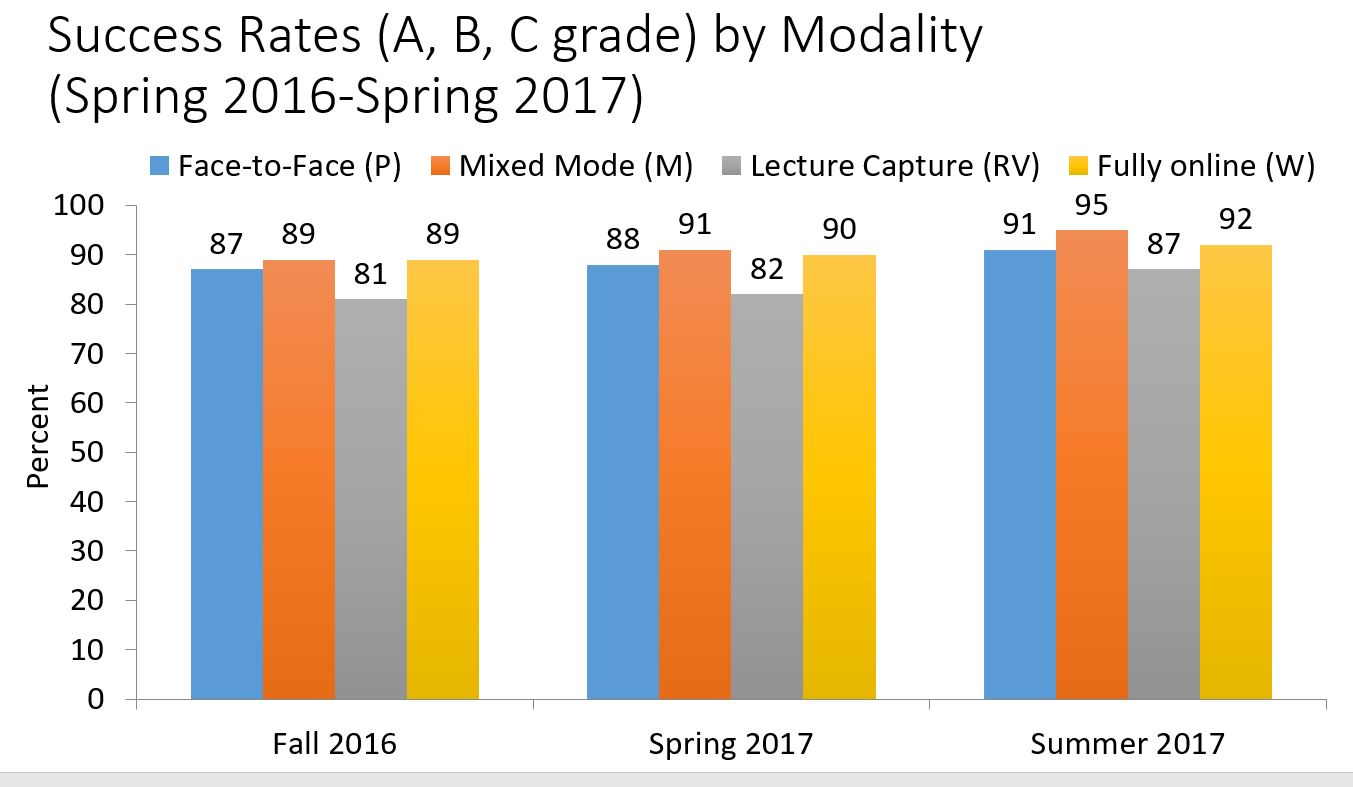

According to a 2017 internal study, 45 percent of students in blended lecture-capture courses called them “excellent” in end-of-semester evaluations. That’s fewer very favorable ratings than for face-to-face (53 percent), fully online (55 percent) and blended learning (57 percent).

The university has also found that the achievement gap for students receiving Pell Grants and for minority students is smaller in mixed and online courses than in face-to-face courses, according to data provided by Cavanagh.

Participation in lecture-capture courses also left something to be desired, Cavanagh said. During the 2017-18 school year, an average of 46 percent of the 3,400 students enrolled in lecture-capture courses watched fewer than half the videos in their course. According to Cavanagh, many students also get in the habit of watching recorded lectures at double speed.

How did the Center for Distributed Learning decide on five class sessions per semester? Why not more?

For a class of 1,200 students, the most that could fit into an on-campus space was approximately 200, Cavanagh said. That means each core course has six sections. Cavanagh’s team did the math and found that any more than five class sessions would have exceeded faculty capacity.

“In a perfect world, we would have been able to have the students meet more than five times a semester,” Cavanagh said. “It was kind of a very practical, ‘this is the most that we could squeeze in.’”

Paul Jarley, dean of the College of Business, told the Orlando Sentinel last week that he would need 72 additional instructors to offer the core courses in a lecture format with 120 students per section.

How many hours of course work are expected outside of class?

Students are expected to spend the same amount of time learning outside of class as they would have if they had attended a lecture, Cavanagh said. His team worked with instructors to ensure that they weren't asking students to do more work online than they would have had to do in class.

“Sometimes when you’re designing a blended class, instructors keep everything they had face-to-face. Even though you’re reducing the seat time, they’ll put the equivalent amount of stuff online,” Cavanagh said. Even though students are experiencing the course in two different modalities, the total workload should be equivalent to an experience in only one modality, Cavanagh said.

How did faculty members develop their group assignments?

The Center for Distributed Learning urged instructors to think of their course in terms of five key themes that students should take away, according to Cavanagh. Each class session would tackle one of those themes.

Dean Cleavenger, a lecturer of management, said he wants students to feel that they’re getting something from each class period that they couldn’t have gotten online. Otherwise, he said, they won’t feel compelled to attend mandatory sessions.

Cleavenger’s group project sessions focus on concepts like delegation and motivation that aren’t easily elucidated in writing or resolved in a didactic worksheet.

Though Cleavenger strives to make his group sessions distinctive and memorable, some of his colleagues prefer a slightly more traditional approach, like an in-class quiz, Cleavenger said.

How do the instructors assess whether or not students are learning from the in-class group project assignments?

It varies by instructor. Cleavenger offers quizzes at the end of some group sessions. Sometimes he also asks students to complete a brief assignment in preparation for the in-class exercise -- their participation gives him a sense of how seriously they’re taking the assignment.

What’s the nature of the professor’s involvement in the active learning assignments?

Again, it varies by instructor, but in general, the faculty member serves as facilitator and master of ceremonies. On at least one occasion so far this semester, a professor wasn't present at one section of an in-class session because he had another course to run at the same time, according to students in his class. Some students who signed a petition calling for reforms expressed frustration that they didn't have more access -- or any -- to the instructor during class time.

Cleavenger posts learning outcomes at the start of each session and then reviews them with students after the active portion is complete.

Because Cleavenger only has a few opportunities to make an impression, he has felt performance pressure, he said. “It’s like having a good joke and laughing at it in your living room,” he said. “Will it work with an audience?”

What’s the role of the teaching assistant during the group project sessions?

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, it varies by instructor. Generally, they serve as extensions of the instructor’s presence -- walking around to talk to different groups, fielding emails, helping with setup.

“They’re working for me, following my direction,” Cleavenger said. “They’re just more of me.”

Before this semester started, Cleavenger’s department chair offered him additional help in preparation for the large group of students. In addition to his standard two graduate assistants, he now makes use of four Ph.D. students who perform a similar role.

Jarley cited the teaching assistants as one of the key factors that make the reduced class time format more costly to the institution than the lecture-capture model. According to a university spokesperson, a course in the reduced class time format costs $24,000 more per semester to produce than a lecture-capture course.

What kind of professional development was offered to faculty members who moved to the blended learning model?

Instructors teaching in the reduced class time format were required to enroll in a noncredit course created by the Center for Distributed Learning to strengthen online teaching skills. Fittingly, the 10-week, 80-hour course is offered in a blended format, with three face-to-face sessions and online elements as well.

The digital learning office also connected instructors with an instructional designer, who serves as the faculty member’s designated consultant. Cleavenger said he’s met with his designer partner five times.

Cleavenger said instructors have also been encouraged to collaborate on strategy together, rather than each offering their own material that might overlap with other classes. “That’s kind of a work in progress,” Cleavenger said.

Is the root of the problem that the College of Business simply has enrolled more students than it can handle?

Maybe.

“It’s a valid question,” admits Cavanagh, who goes on to say that the university plans to continue serving as many students as possible without sacrificing quality. During a public form last Tuesday, the university's president, Dale Whittaker, characterized the new modality as a “grand experiment in some very important foundational courses” and expressed a desire to adjust based on student feedback.

What have the students been doing?

During a public forum last week with Whittaker, several students -- including a representative of the reform group that has been petitioning the business college -- raised concerns about the reduced class time format. (The petition’s ranks have swelled to more than 2,400 students.)

Michael Wensinger, who created the reform group, met on Monday with Jarley, dean of the business college. Wensinger told “Inside Digital Learning” the meeting was “very insightful” and that the dean plans to engage him going forward on possible techniques for helping students adapt to the new format.

Jarley was receptive to ideas like making each group project session longer and allowing students to choose their own groups, Wensinger said.

Is anyone else at the institution thinking about the "reduced class time" approach?

Is anyone else at the institution thinking about the "reduced class time" approach?

Nick Shrubsole, a lecturer of humanities, religion and cultural studies, plans to introduce the format in next semester’s iteration of his 60-student Encountering Humanities course. The twist: the current version of the class is offered fully online.

Shrubsole has been looking for ways to make discussion in his online classes more dynamic. He first heard about the reduced class time format during a faculty meeting last summer, and he thought it might work well with his course.

He plans to break the class into three sections and ask each one to attend four in-person sessions throughout the semester -- one for each of the course’s three main modules, preceded by an introductory session. Students will complete activities like an art project and a film screening ahead of time and then come to class to critique products and discuss analysis.

“Reduced/active is just another blended mode,” Shrubsole said. “It offers a lot of opportunities from the best of worlds.”

Though some students might be reluctant to enroll in an online course that also requires them to be on campus, Shrubsole thinks there’s enough interest in the course from students close to campus. Right now he plans to host all of his class sessions back to back to back on Fridays, but he’s willing to make adjustments if he finds that students have a wide variety of scheduling preferences.

Shrubsole also teaches an online version of the course with 300 students, but he’s not yet sure whether he could handle the number of in-person sessions he would need to keep each section small and intimate.

What’s next?

Based on some early evidence, additional class sessions might not solve the problem, though. Cleavenger took a poll after this semester’s first class session and found that 400 students wanted him to hold an additional session for exam review and Q&A. Cleavenger pulled some strings to secure a meeting space that fits 200 students, but only 30 showed up, he said.

“If you build it, they won’t necessarily come,” Cleavenger said. “I wasn’t surprised, but it’s disappointing. I’m an educator and I want to educate. I can’t do that if they don’t show up.”

UCF and other institutions are confronting a major challenge of reconciling student perceptions of learning with a longer-term view of effective teaching practices, according to Alana Dunagan, a senior research fellow for higher education at the Christensen Institute, a nonprofit innovation think tank.

"This is a sense of 'I’m not getting what I thought I was paying for. What I thought was I paying for wasn’t that good to start with. But as a student, I have no way of knowing that,'" Dunagan said.

Dunagan compares the situation at UCF to the business model at Western Governors University, where students enroll with the expectation of a seamless online experience. At UCF and many other places, meanwhile, learning models are diverse and still evolving.

"I think there’s more research to be done," Dunagan said. "I don’t think we’ve settled all the questions."