You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

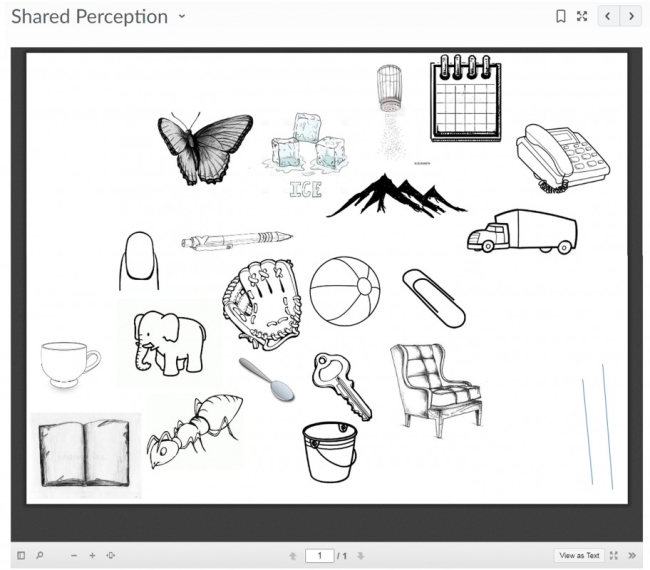

In the shared perceptions online game, medical students at Rosalind Franklin University sort pictures into groups of their choice and then discuss their choices with peers.

Courtesy of Catherine Gierman-Riblon/Rosalind Franklin University

Trial and Error is a recurring feature from “Inside Digital Learning” that examines the successes and struggles of technology initiatives on campuses and in classrooms, on the assumption that we learn as much, if not more, from failure as from triumph. Have ideas for future columns? Send them to mark.lieberman@insidehighered.com. And be sure to comment below the story with thoughts and ideas for this institution.

The Institution: Rosalind Franklin University, a graduate-level health science institution in Chicago.

The Challenge: The university offers programs centered around an atypical health-care model known as “interprofessionalism,” in which teams of clinicians from various professions address a patient’s problem. In this model, “the clinician with the knowledge, skills and abilities to best address the patient’s problem at that moment steps up to lead the team,” according to Catherine Gierman-Riblon, assistant professor and chair of the interprofessional health-care studies department. Proponents of the interprofessional model, more popular among health-care providers in Canada and the United Kingdom than in the United States, argue that it eliminates the potential for poor communication to cause errors.

The interprofessional model lends itself to active learning strategies described by Gierman-Riblon as “games for serious learning.” In face-to-face programs, 500 first-year students in a single class break into teams to play “naïve games” -- which require no subject-matter knowledge -- that ideally lead to a deeper understanding of the course material. Examples include two sorting games that force students to reflect on their perceptions of their work; a memory game that requires students to recreate collections of shapes using dominoes; and a puzzle game that prompts reflection on the nature of collaboration.

Revamping instructional design and the semester schedule.

Creating virtual reality "as memorable as the O. J. Simpson trial."

Students and alumni lead an OER factory.

The Goal: Gierman-Riblon and her team wanted online students to reap comparable benefits from these games. She thought they in particular could benefit from an exercise that compensates for the lack of face-to-face encounters.

“Neutralizing the diversity with a common experience facilitates their engagement in more meaningful conversations,” Gierman-Riblon said.

Gierman-Riblon teamed up with project lead Bill Gordon, an instructor who teaches collaborative teamwork, plus two professors with graphic design and technical expertise, to translate four face-to-face games into the online format. Those games are now in use in two graduate-level online courses. As is often the case, translating a face-to-face exercise to a digital format takes some finagling.

The Experiment: Online versions of face-to-face games require a substitute for instantaneous interactions.

“It became necessary to suspend the urgency element, which is a bit like trying to do a carpentry project while leaving out a very important tool,” Gierman-Riblon said.

The team adopted the same “low-barrier, low-resource” approach that led to the creation of the face-to-face games -- faculty members should be able to easily create and manipulate the games, just as students should be able to easily draw lessons from them. That meant making liberal use of PowerPoint and Adobe products, rather than investing money and time learning complex tools. The primary cost of these efforts came from staff time.

Gierman-Riblon said she was concerned at first that colleagues would scoff at her efforts, or deem them “less than” the high standards of her department. But she and her colleagues have discovered at recent conferences in Wisconsin and New Zealand that gamification has a more positive connotation than she thought.

What Worked (and Why): The task of finding ways to make asynchronous online gaming engaging forced the designers to “stretch their own thinking and understanding even further,” Gierman-Riblon said. For one game that uses flash cards with words, the team decided the online version should use pictures instead, giving students more room to indulge their interpretations during the reflection portion of the activity.

What Worked (and Why): The task of finding ways to make asynchronous online gaming engaging forced the designers to “stretch their own thinking and understanding even further,” Gierman-Riblon said. For one game that uses flash cards with words, the team decided the online version should use pictures instead, giving students more room to indulge their interpretations during the reflection portion of the activity.

“The [upshot] of that is that the online game is informing us about how to make the face-to-face game better,” Gierman-Riblon said.

The mechanical process of digitally recreating the games wasn't always clear from the start, but figuring it out was rewarding, according to Gierman-Riblon. For the puzzle game, the team hired an in-house artist to create a new image in order to avoid copyright concerns that could result from snatching a generic puzzle image from the internet. Then the team created the puzzle in Adobe Captivate, imported the artist's image to overlay it atop the finished game, exported it as an HTML5 article and uploaded it to the Join.Me platform, where students can complete it at their leisure.

One step in creating an online game is writing out a list of steps for completing it, which forced the team to reckon with how it explains the face-to-face games to students. Gierman-Riblon said her team has come to the realization that the games are valuable not only as activities but as tools for reflection that facilitate learning.

What Didn’t (and Why): At first, the team took pains to make the games look as attractive as possible. But in one case, “pieces that were supposed to remain grouped together to make an element of the game sometimes separated,” Gierman-Riblon said. Pieces with fewer complex design elements solved that problem.

Some online games simply turned out not to be fun, which defeated the purpose of including them in the class. Others simply weren’t feasible to create with the available tools. Still, that process can lead to more valuable revelations.

“What doesn't work in one instance may be resurrected for another,” Gierman-Riblon said. “The ultimate goal is not to make a particular idea or game mechanic work, but rather to develop activities that point to the learning that has been targeted.”

What’s Next: Gierman-Riblon hopes the games can be incorporated into courses in the institution's online program for health-care education as well. The team has also flirted with the possibility of gamifying an entire course so that it’s designed at the macro level with gaming in mind, and infused with games at the micro level as well.

Face-to-face, the institution has embarked on building a 20,000-square-foot simulation hospital as a “game board” on which learners will become avatars who level up based on their success at various challenges. One possibility is giving students a constantly shifting mock emergency scenario, challenging them to complete a “limited-time ambulance” ride complete with appropriate communication during a handoff to a waiting clinician at the hospital.

“Scale will become an enveloping part of the activity -- a term-long class, or a physical environment for immersion learning in face-to-face activities,” Gierman-Riblon said.