You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Richard Garrett

Chris Kosho/NRCCUA

BOSTON -- Does online education help cities and states increase postsecondary access and success for the undergraduate students who need it most?

No hourlong presentation can reasonably purport to answer that question, and the kind of data that might present a clear yes or no verdict probably don't exist yet. But Richard Garrett, chief research officer at Eduventures, wove together an intriguing set of statistics and assertions at the group's annual summit, Higher Ed Remastered, here last week.

Using federal data on online enrollments, prices and completions, as well as state-by-state data from the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements, Garrett made the case that online education has helped to suppress the tuition prices adult students are paying, and that colleges that enroll many students online are significantly increasing access to higher education for adult students.

But the data also show that students at those institutions graduate at sharply lower rates than do those at institutions where in-person and blended modes of learning dominate.

That "conundrum," as Garrett called it -- that online education "widens access but on average lowers students' odds of completion" -- raises questions about the extent to which colleges, states and others should be pushing fully online education or more blended forms of learning, which may be less practically available and more expensive but more likely to result in students' success, he argued.

"A lot of schools have rushed to fully online as the only thing adults will tolerate," because of those programs' convenience and affordability, Garrett said. "But these data suggest that you can't just go to convenience and cost to accommodate busy adults, if the evidence says that blended may be best for them educationally."

Garrett said that as a longtime student of the online learning marketplace, he wanted to tap into newly available sources of data to try to put together a portrait of the landscape that accounted for local and regional differences and tried to assess not just where students were enrolling but how they were faring educationally.

Among the sources of data he used were the federal government's Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, which has been counting online enrollments for just a few years; new IPEDS data on outcome measures, which for the first time now include students who are not enrolled full-time and for the first time and follow them over eight years instead of six; and statistics from NC-SARA, which track online enrollments at the state level.

Much of Garrett's presentation mined those data to show the extent to which different states and cities (especially those where smaller-than-average proportions of adults have bachelor's degrees) appear to lean heavily on online education to increase postsecondary attainment.

Among the data points he presented:

- While the enrollment of traditional-age undergraduates rose by 3 percent from 2012 to 2017, the number of undergraduates studying fully online grew by 11 percent over that time (to about 2.25 million), while the number of adult undergraduates actually shrank by 23 percent.

- Roughly 13 percent of all undergraduates are studying fully online, and roughly 8 percent are studying fully online at an institution based in the state where they live. "So while online is viewed as throwing geography to the wind, freeing up the student to study not just where they live," that's not necessarily how the market is playing out, Garrett said.

- Several cities whose residents have the greatest amount of economic need also have higher-than-average proportions of students studying online at in-state institutions, suggesting that those cities have decided that online education can play a role in closing economic gaps. In Birmingham, Ala., for instance, 12 percent of all residents are studying fully online at colleges within the state's borders, while in Detroit and Hartford, Conn., the figures are just 5.3 and 5.2 percent, respectively.

"In some cities, online is playing a role where need is greatest, in others it's a bit part," Garrett said. "Do these cities wish online was there, or have they deliberately rejected it as a potential solution?"

Few cities have a higher education strategy at all, let alone an online learning strategy. But many states have set goals for higher education attainment for their citizens, and Garrett sought to compare how the states with the lowest rates of postsecondary attainment are utilizing online education.

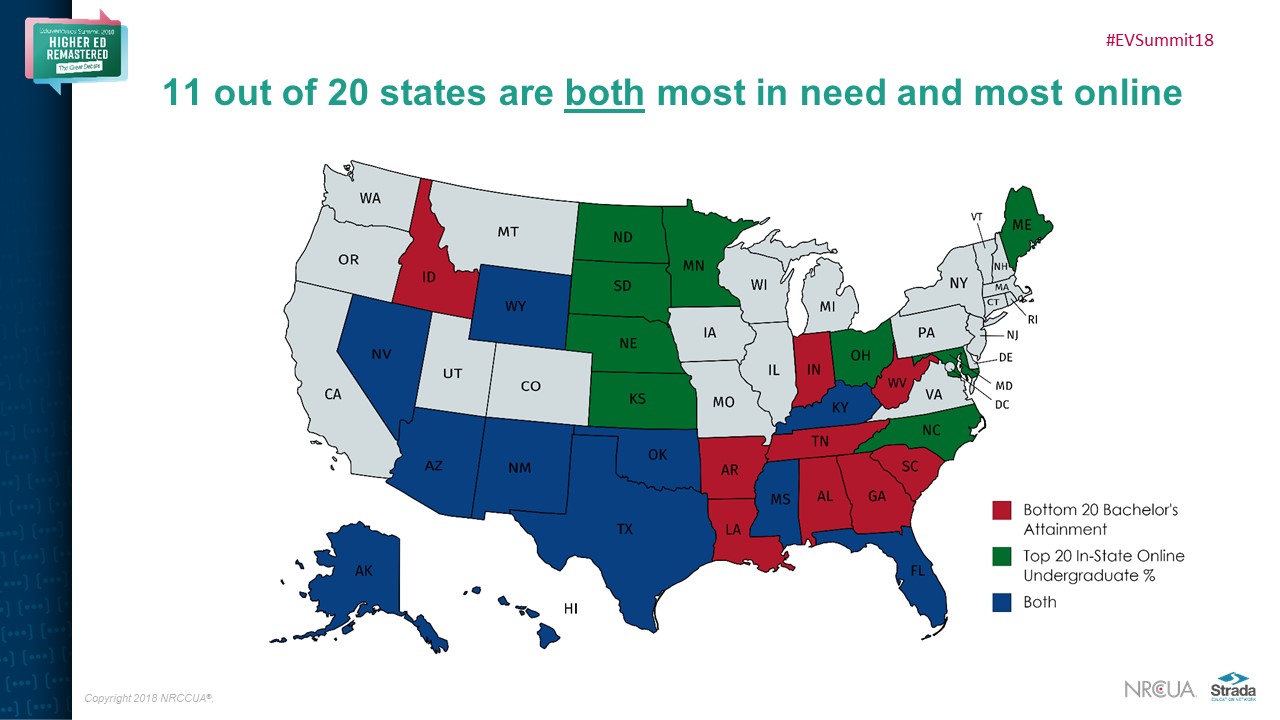

The map below shows that 11 of the 20 states with the lowest rates of bachelor's-degree attainment (which Garrett acknowledged is only one measure of college attainment) also appear on the list of states where the largest proportions of residents are studying online at in-state institutions.

And this map shows that 15 of the 20 states with the lowest rates of bachelor's degree attainment are in the top 20 states in terms of the proportion of their students who are at institutions that significantly blend online and in-person study.

Judging the Performance of Online-Only Education

As states, cities and individual colleges decide on how best to provide higher education in an equitable way, what should they be considering -- and what evidence is there so far about what works best?

Garrett sought to tap existing data to gauge how well online education was delivering on its ability to make affordable, high-quality learning more broadly available. The fact that the available data are imperfect, as he pointed out, didn't stop him from gauging some national patterns.

Online is clearly where the growth is, especially when it comes to enrolling adults. The slide below shows the change in where those aged 25 or older were enrolling from 2007 to 2015, based on the percentages of colleges' students who are studying online. In 2007, colleges where "very low" proportions of students study entirely online enrolled 31 percent of all adult students, while institutions with "very high" levels of fully online enrollment enrolled about 12 percent of older students.

By 2015, the latter category of institutions enrolled 28 percent of adult students (see the rising red line in the graph below), becoming the clear leader.

The picture on affordability looks good for online, too, Garrett noted. As the slide below shows, net tuition and fees at colleges with no students studying online (the "zero" online institutions represented by the black line at the top) rose by 12 percent between 2012 and 2015, while those with "very high" online-only enrollments saw their prices drop by 8 percent. (Tuition rose by 16 percent during that period at colleges with "high" online-only enrollments, an anomaly Garrett said would require further study.)

Garrett acknowledged the drop in tuition revenue at the heavily online institutions could be attributed to the decline of for-profit colleges, but many of the fastest-growing colleges online are nonprofit institutions that also are using their scale to keep their prices down, he said.

Access? Check.

Affordability? Check.

Student success? Not so much, Garrett suggested.

Citing the first-ever federal data looking at eight-year outcomes of all postsecondary students, including those who are not first-time, full-time students (to which many federal education databases have historically been limited), Garrett noted that students enrolled at institutions where a very high proportion of the instruction is delivered fully online were significantly less likely than students at other types of colleges to earn a credential from the same institution within eight years.

By comparison, students at colleges and universities where a very high proportion of their students take at least some of their courses online performed similarly to those at colleges with little online instruction, especially for part-time and non-first-time students. That is consistent with much of the research on learning efficacy that tends to show blended learning outperforming fully online and fully in-person learning.

The Eduventures summit is heavily populated by officials from institutions active in the online learning space, and Garrett was careful not to imply that he thinks investing in online learning is the wrong strategy.

But he said it was important for institutional leaders and state policy makers to make sure that they are not "trading convenience and flexibility for truly transformative [student] outcomes," he said.

An institution needs to push fully online programs if it wants to compete in a national higher ed market, but how many colleges can compete at that level? he said.

Or should more colleges, Garrett wondered, be focused on serving residents in their states, saying, "We'll give you enough online … to make higher education practical, but give you access to campus, to faculty, to other students … which may be the more engaging experience"?

"The data may not be perfect enough yet to answer questions like these," Garrett said, "but they do allow us to be asking better, more rounded questions."