You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

click to see full image

Stanford University

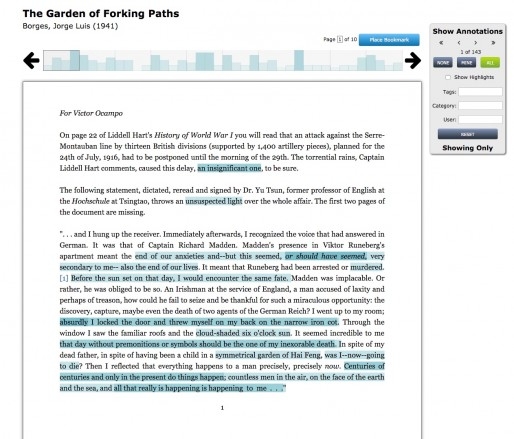

Even with a printed textbook, a highlighting marker can't do this: A free online program that allows students to annotate digitized content is helping learners analyze and debate the meaning of humanities topics and write more in-depth papers.

Developed at Stanford University, the Lacuna platform lets users highlight key passages and create notes to record questions, comments and reactions to the text. The program allows for the sharing of ideas and questions because the students’ annotations can be seen by their peers and instructors, said Brian Johnsrud, co-director of the Poetic Media Lab, a digital humanities laboratory hosted in Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis. Johnsrud created Lacuna with Mike Widner and Amir Eshel.

“This facilitates a blended or flipped classroom situation,” he said. “And it means that conversations, debates and dialogue on the meaning of the text aren’t just isolated to in-classroom time.”

The open-source tool is providing humanities professors and students with a taste of the expanding range of optical character recognition (OCR) materials that their counterparts in STEM fields enjoy, said Johnsrud, who teaches literature and media studies courses.

“I realized that it’s really a shame in this age of [massive open online courses] and with all these great tools out there designed for STEM classes that there’s not as much available for the kind of critical thinking content we want to teach in arts and humanities,” he said.

Threading Annotations

Lacuna builds on early advances in annotation programs, such as MIT’s Annotation Studio but with features found nowhere else, Johnsrud said.

“We wanted our program to allow students to step back from the hundreds and thousands of annotations and to sort them to get a meta understanding of themes and topics and how they intersect across the course material,” he said.

A key feature of Lacuna, the Personalized Sewing Kit, allows students to categorize annotations, helping them to identify patterns across and within texts by stitching together excerpts and notes into collections called threads. Students can then arrange the treads to create outlines, writing assignments or essays.

“So for example, after reading a dozen or so novels and 30 articles over a semester, the student who is writing a paper about globalization and gender can ask the program to show all of his or her annotations on those topics,” Johnsrud said.

In addition, a dashboard provides instructors with heat maps showing which parts of the text have the most annotations, which can guide them in leading discussions. Foothill College English professor Ben Amerding, who has used Lacuna in writing and composition courses, said the program helped him to see how his students were “reacting to, interacting with, understanding, and misunderstanding the texts.”

If a student had a hard time with a passage, seeing how other students annotated it would sometimes help the struggling learner with comprehension, he said.

Launched in 2013, Lacuna has been used in 39 Stanford courses, including political science and writing classes. Other institutions across the country are using the program, including at least 40 that Johnsrud knows of.

The latest version has new features that allow students to synchronize and connect Lacuna coursework across any of their classes that are using it.

“This helps break down interdisciplinary barriers and facilitates cross disciplinary thinking,” said Johnsrud. “For a non-humanities student it gives them the opportunity to see how ideas from philosophy or Shakespeare interact with a class in politics."

The mobile features also were improved, something many students appreciate. “We’ve especially noticed in community colleges or commuter schools where students aren’t residents that they really like being able to do their course reading on the way to school and back on their phone or iPad,” he said.

Learning Curve

Jed Dobson, an instructor at Dartmouth College, adapted Lacuna to work with the edX MOOC system for his online course on 19th century American literature. He said there was a small learning curve in getting the program to interact with edX but the Lacuna team helped guide him through the process.

At first, some students balked at having to leave edX to access Lacuna, Dobson said, but the program makes it as easy as possible with a one click button that takes edX users to a pre-authenticated window.

Amerding, who often asks his students to read news articles the day they are published, said he wishes Lacuna could be updated more easily. “The process was so arduous ... that I didn't even try,” he said. “However, when they were willing to upload texts for me ... they were always helpful.”

Johnsrud said Amerding decided not to upload his materials, and said in an email that "he is not representing the platform as it's used by 99.9 percent of users." However, Johnsrud said he recognizes there is a time investment involved in uploading articles and texts and that a new version of Lacuna available this fall will make text uploading somewhat easier.

“We share this challenge with edX, Canvas and other platforms where faculty have their materials as PDFs, which need to be copy-and-pasted into web browsers,” he said. “Because of that, it's a good time investment for faculty with RAs or teaching staff who can assist in the editing.”

The bigger challenge to using the program was pedagogical, Dobson said, and involved the new process of asking students to annotate text as they read. Plus, some students (especially older, nontraditional learners) prefer to read assignments in hard copy.

“If you’re going to have students mark up the text and look at other student’s notes—when you weren’t having them do that before--you have to rethink what they’re doing and why they’re doing it,” he said.

Dobson decided not to grade the annotations but instead encouraged students to use Lacuna to generate material for traditional assignments.

“The assessment [was] to write a paper, but the prompt for that paper asked them to go back and use the work they have done with the annotations, so it became a building block for my assignments,” he said.

The program increased the amount and diversity of annotations that students used, leading to better written papers, Dobson said. Just as important, it helped the 2,500 students in the online class feel connected to each other, he said, and those that did go fully digital probably saved about $90 by not buying hard copies of the nine texts required for the course.

Finally, Lacuna helps professors overcome one of their biggest challenges: determining whether a student has read the assignment.

“They know that you know that they did the reading,” Johnsrud said. “Not in a surveillance kind of way but in a way that they can share what they’ve learned. It can be frustrating to read a 700-page Russian novel and not have a chance to share what you thought about it, which can happen in a large class discussion.”