You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In our 28- country comparative study of academic salaries (See "Faculty Pay Around the World" by Scott Jaschik), we attempted to convey the value of different salaries by converting salaries to PPP, a mechanism that allowed us to compare the "buying power" of salaries in local economic context. The use of PPP has caused a lot of confusion. In this essay a member of the research team, Gregory Androushchak, attempts to clarify the value of using PPP for a complex comparative study like this one.

"Paying the Professoriate: A Global Comparison of Compensation and Contracts" has provoked a lot of debate since its release. A number of the comments deal with our data on faculty salaries and a few of the correspondents wondered if these are some other countries under the same name. Most of the confusion arises due to conversion of salaries in local currencies into comparable international US dollars. It turns out to be not as straightforward as simply applying exchange rates to salaries in local currencies if we want to get something meaningful. So some clarification is needed regarding conversions and comparability of academic salaries. And this is what this post aims to do.

To start with, our original data on academic salaries comes in local currency units - Ethiopian Birr, Russian Rubles, Chinese Yuan, etc. The most immediate solution would be to find data on the currency exchange rates for our sample of countries and convert everything to US dollars.

This approach is relevant when we are trading goods across the border. That is, suppose we want a particular good produced in other country, and so to have it, we need first to buy foreign currency and then buy the good with it. Therefore, we use exchange rates to see, how much we should pay for a particular imported good.

This has immediate application in the academic context as well. I do not want to be so cynical an economist as to compare consumer goods to the academic profession, but let us address an example. Suppose we are an Ethiopian university and we want, say, a US professor to teach a 5-day course to grad students. Obviously, we need to pay him or her in US dollars. If we agrees to US$ 5 thousand, it means we need to secure about 50 thousand Ethiopian Birr from our budget - we have to use the currency exchange rate for this.

Now suppose we want (just as we did in our book) to compare the welfare of professors in Ethiopia and the US. An economist would do that by comparing consumption of these two professors, that is, in terms of their food and other purchases. If a US professor buys more goods he or she might be said to be better off than an Ethiopian counterpart.

But how can we obtain such information? In practice economists simplify the task greatly for the sake of getting relevant estimates. They define a so-called consumer basket ‘filled’ with goods and services that individuals normally consume in the quantities that are normally consumed. Then they estimate the value of the basket in local currency (for example in Ethiopia in Birr) and the value of that same basket in the other country (for example in US in dollars). By dividing the value of the basket in Ethiopia in Birr by the latter in the US in dollars economists obtain a PPP estimate. The PPP estimate, therefore, says how many Birr in Ethiopia one needs so to buy the exactly equivalent consumer basket in the US.

Hence, if the top rank professor in Ethiopia earned 6.2 thousand Birr in 2008, the PPP rate says that he could buy goods in Ethiopia that are equal in value to what would cost US$ 1.6 thousand in the US. However, if he wanted to go to the US, his monthly salary would be sufficient to buy goods that cost only about US$ 620 in the US. Note, that the key point in all this logic is where the professor wants to spend his or her money.

Is it possible to provide some meaningful interpretation to the difference between exchange rate and PPP difference we are actually talking about? I think, yes.

Let us go back to the Ethiopian example. In 2008 the PPP rate was 3.91 Birr per US$ 1, while the exchange rate was 9.96 Birr per US$ 1. The ratio of exchange rate to PPP (which is 2.5 for Ethiopia) says how much more a professor can buy locally than internationally for a unit of her salary. In other words, it shows international competitiveness of a unit of local faculty salaries: the higher the ratio, the lower the competitiveness.

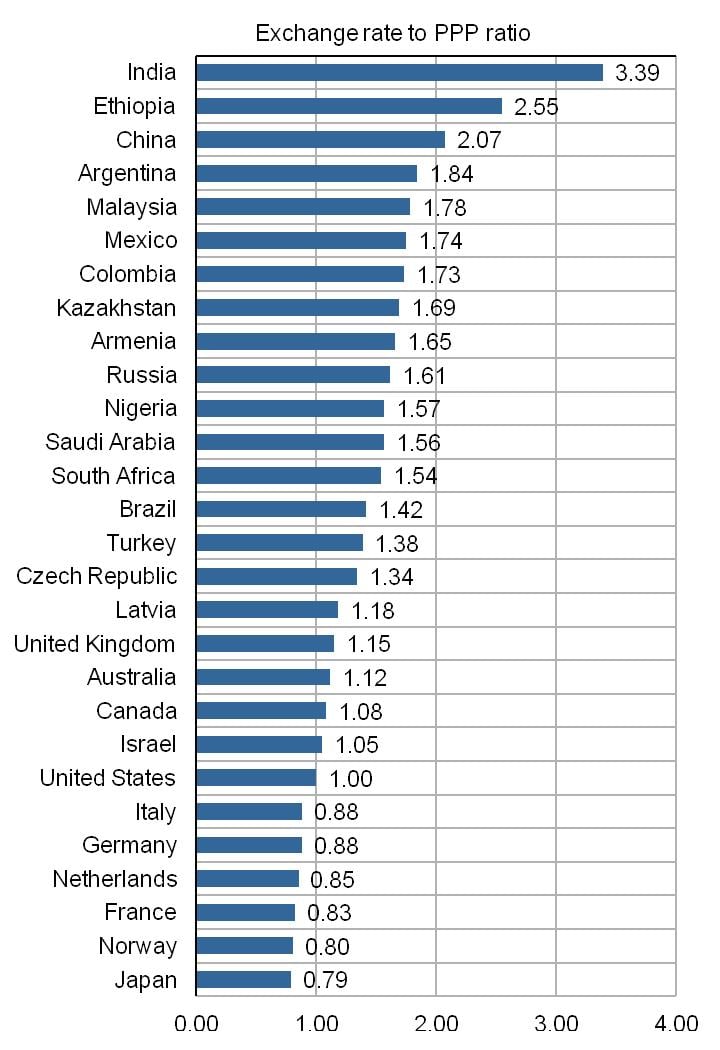

The figure above presents exchange rate to PPP ratios for the countries that we consider in our book. And it is clear that Ethiopia is among the countries with very low international competitiveness in terms of units of academic salaries, on par with countries, such as India, China and other. While at the other end of our sample, the international competitiveness of academic salaries in Japan and the European countries is quite high.

This exchange rate to PPP ratio has particularly important meaning for academic policies in countries where universities compete internationally for faculty and have to pay higher salaries for international professors compared to what they would pay local professors.

So, summing up:

- PPP rates are more accurate for comparing local welfare of faculty in different countries because it captures the value of goods and services that can be actually bought in these countries for US$ 1 rather than how many units of local currency one can exchange for it.

- The ratio of Exchange rate to PPP shows international competitiveness of a unit of faculty salaries and it turns out that the least competitive in this sense in 2008 were India, Ethiopia and China, while the most competitive - Japan and European countries.

- For countries, such as India, Ethiopia and China hiring international faculty is expensive not only due to local and international differences in salaries, but also due to the exchange rate-PPP effect. In these countries any given salary buys more goods and services locally than abroad.

Gregory Androushchak is Advisor to the Rector and Researcher at the Laboratory for Institutional Analysis at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow.