You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Three months ago, my family departed for two weeks in Rome, taking up residence in a guest house a short walk from the Colosseum. Back at home, precisely two months after our trip, I found myself walking past the football stadium roughly the same distance from our house as the Colosseum was from our guest house. The parallels stuck.

During our sun-drenched, meltingly hot, Roman July strolls to the Colosseum, we fought our way through vendors hawking bottled beverages, panini, hats, and knickknacks of every imaginable size, shape, and form. During my walk past the stadium, I squeezed past stands selling bottled beverages, hot dogs, hats, and knickknacks of every imaginable size, shape, and form.

When touring the Colosseum, a highlight is the archway through which the gladiators passed from their underground cells into the ring where they confronted catastrophe. At the football stadium, the players run from their locker rooms through an arch and onto the field where they confront catastrophe.

At the top of the Colosseum, one now passes through a glassed-in museum, eerily reminiscent of the glass boxes for the well-heeled and well-connected at the top of the football stadium. Our post-modern vestal virgins cheer at the side-lines, rather than view from the location now taken up by the endzone. The first row seats at the 50 yard line, where university presidents and prosperous alumni can reach out and practically touch the players, bears greater commonality with the vertical hierarchy of seating in the Roman structure.

Last year at this time, I wrote about the international flavor of a contemporary collegiate homecoming parade. Such pregame festivities also fit within my Roman motif. I think of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s extravagant spectacle in which Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra became history’s greatest Homecoming Queen.

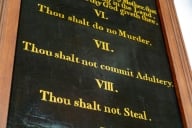

The Forum and the Pantheon manage to keep a cleaner history of our classical inheritance. Noble structures built with the intention -if not the execution- of good governance offer comforting thoughts about humanity’s enduring objectives to improve ourselves and our world.

By contrast, The Colosseum causes immediate discomfiture. Here the senators we imagine idealized atop Rome’s seven hills descended into the valley and watched the vulnerable die terrible deaths. When physicians discuss traumatic brain injury, they link football with warfare. As we learn ever more about the long-term ramifications of football injuries, cheering in the stadium or at the television screen feels uncomfortably close to the Colosseum.

No one sent physicians onto the field to check whether a gladiator’s pupils dilated evenly or joints bent properly. Unlike the Colosseum crowds, football fans cheer not when a player is injured, but when the injured player manages to walk off the field or gives a sign of life. The outrage surrounding Michigan Quarterback Shane Morris demonstrates we do not want contact sports to operate as a direct replacement for battlefield brutality. Nonetheless, no level of padding can fully protect the players who charge one another across the scrimmage line. The announcers who watched Morris take the controversial “concussive hit” used military terminology. They thought Minnesota’s cornerback had “targeted” Morris and that both men ought be removed from play: one as precaution, the other as penalty. Both remained on the field. The rules can only protect players if the players, the referees, and their coaches follow them.

I made my way through the football crowds weeks before Shane Morris stumbled off the field. Ambulances, fire engines, and police cars encircled the stadium to help anyone - player, fan, or passer-by - who came in harms way. These are the signs of civilization that salve our guilt at enjoying a sport that causes students to limp into my office on crutches and lay in dark rooms with concussion-caused-migraines.

Lee Skallerup Bissette views the crisis in collegiate sports through the lense of an athlete who loves athletics. I never belonged to a sports team, and I experienced gym class as a prolonged torment sent to prove my physical incompetence. Nonetheless, my memories of childhood autumnal Saturdays involve college colors, hot chocolate, and loud cheers for a losing team. Who won mattered far less to me than marching bands, mascots, and merriment. I suspect those in the Colosseum cared less about who died than what their neighbor wore and who whispered what to whom.

I want to go to games, eat my hotdog, drink my hot chocolate, and listen to the band. I also want watch the balletic beauty of a running back leaping downfield with lightening speed and the graceful arc of a long pass descending towards a wide receiver's open embrace.

I hope the harm that befell Mr. Morris and so many like him ends now and allows our contemporary coliseums to ascend from the brutal valley to the Palladian Hill of our better selves.