You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti

Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti

Published in February 2019

Those interested in continuing our conversation around “The End of Babies” will enjoy reading and discussing Love, Money, and Parenting.

Part of the thesis of the Sussman New York Times piece is that the fall in fertility across wealthy countries to below replacement levels is being driven, at least in part, by economic factors. The authors of Love, Money, and Parenting -- a couple of economists steeped in the ideas of Gary Becker -- would undoubtedly agree.

For Doepke and Zilibotti, however, economics explains far more about modern families than the decline in baby making.

Curious about the rise of the tiger moms and helicopter parents? Look to economic incentives.

Want to know whom people choose to marry and at what age they will tie the knot? Examine the economic incentives.

Wondering about the probability that you or your friends will get divorced? Again, think about economic incentives.

It is not that the authors of Love, Money, and Parenting believe that individual economic incentives are the only factor in driving family-related choices. The authors freely admit that other forces, such as public policy and religious beliefs, can also exert influence. However, it is always the case the economic incentives work as magnifying or countervailing forces to other factors, such as policy.

For instance, the generous parental leave policies and the availability of high-quality subsidized childcare in Denmark serve to counteract somewhat the economic forces that are driving down the baby making. The total fertility rate (TFR), a measure of the expected number of babies that a woman will have in her lifetime, is 1.7 in Denmark. This TFR is above the E.U. average 1.6, and well above that of Italy or Spain (1.3). The Danish TFR, however, is still well below replacement (2.1). Who knows what the TFR would be without all that subsidized daycare and generous parental leave?

Those interested in the relationship between economic inequality and families will find much to think about in the pages of Love, Money, and Parenting. For Doepke and Zilibotti, tiger and helicopter parenting should not be condemned as irrational. Instead, intensive parenting is a rational response to an increasingly winner-take-all economy.

One’s place in the economic hierarchy (which includes access to quality housing, health care and public education) is mostly dependent on one’s job. As the labor market premium for skills has increased, parents are making a rational choice to do whatever is necessary to provide their kids with the hard and soft skills required to compete.

The effect of growing inequality on parenting is, however, not all bad. The fact that our kids are likely to be working in jobs that don’t exist today, and that they will need to change jobs many times in their working lifetimes, has led many parents to adopt a more authoritative, as opposed to an authoritarian, parenting style.

An authoritative parenting style is one that is involved, present and invested in the child’s success. Rather than enforcing a rigid set of “proper” behaviors and relying on punishments as a motivator, authoritative parents attempt to act in accordance with the child’s interests and strengths. The diffusion of authoritative parenting styles, in addition to greater parental investment in young children, is inarguably good for kids.

The arguments in Love, Money, and Parenting are made more convincing by the international perspective and experience of the book’s authors. It is refreshing to get perspectives from outside the U.S., as we learn about the economic and policy environments related to family choices in countries such as Germany, Italy, Sweden, Japan and China.

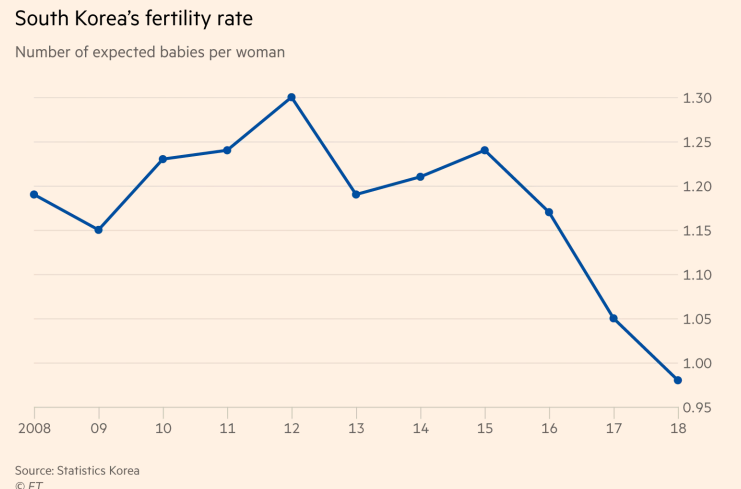

My one complaint with Love, Money, and Parenting is the book does not grapple at length with the possibility that fertility has the potential of following the South Korean model. The TFR in South Korea is 0.98. In a country of 51 million, only 327,000 babies were born last year.

I’ve visited Seoul twice in the last few years. The absence of babies and small children is striking.

On each visit to Korea, I come home thinking that this same thing could happen in the U.S. South Korea is ahead of the U.S. in rolling out fiber internet and now 5G cellular. The U.S. will eventually catch up with South Korea in connectivity. The question is, will that technology catch-up also coincide with a demographic convergence?

I don’t think that we are taking the possibility of the U.S. falling to a TFR of below 1.0 seriously enough.

Love, Money, and Parenting would have been a better book if it took some time to explore -- even if ultimately rejecting -- the possibility of the U.S. following South Korea into the land of no babies.

What are you reading?

Source: FT. South Korea’s birth rate falls to new developed world low.