You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

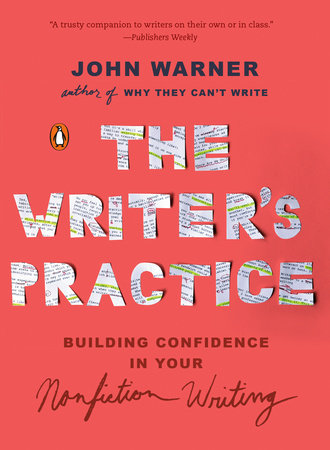

I am not going to write a review of John Warner’s latest book, The Writer’s Practice: Building Confidence in Your Nonfiction Writing, even though it’s full of great ideas for developing yourself as a writer, whether you are a student in a classroom, an instructor at the front of a classroom full of students convinced they aren’t writers after years of being told they are doing it wrong, or if you’re sitting at your keyboard wanting to get better at writing but feeling a sense of dread instead of a sense of possibilities. Unlike handbooks designed for the composition course market, Warner doesn’t explain the rules for commas, capitalization, or what a cover sheet for your term paper should look like. He doesn’t even recap citation rules, which in my experience is the only section of writing handbooks that students routinely use.

Instead of reviewing this book, I’m pondering my own questions. What if librarians presented research to students as a practice? What if we stopped implying it's a set of skills used to complete assignments in school (including coaxing sources out of baulky databases) and instead suggested it's a thing we all do and could do better if we practiced being curious? If we created a book like Warner’s, only about finding stuff out instead of about writing, what questions would head up our chapters? Actually, we could repurpose many of the same questions. Writing is a process of finding out what you want to say, often in conversation with what others say, and that involves practicing being a person who can find stuff out - and knows why it matters.

The problem, of course, is that people who help students learn how to find stuff out are typically doing so in service to others, just as the creative and hard-working people who teach first-year students to write are expected to prepare students to write academic prose with as few mistakes as possible for their future courses, which is not to be confused with being able to write.

Students are in a similar bind. Sure, they may want to be able to write and find stuff out, but what they’re really worried about is that paper due next Wednesday and how to avoid getting a bad grade because of not knowing what the teacher wants. Warner already tackled these structural issues in his recent book, Why They Can’t Write (which I did review). That said, I suspect students who do the kind of writing proposed in The Writer’s Practice could relax because every one of Warner's prompts asks students to think about audience and the appropriate process for addressing its expectations, making rhetorical choices a fundamental part of all writing - good prep for figuring out what teachers want.

For librarians, the challenge is trickier. Even though nearly everyone bemoans the limits of cramming the world of information literacy into single class meetings scattered through the curriculum, the “one shot” remains a mainstay of our instruction opportunities. Even if we meet with every first year student more than once, the focus is usually on how to use the academic library to accomplish academic writing tasks, which is not to be confused with being information literate. Developing the practice of curiosity – that’s a job for the entire faculty.

The structures or our work as librarians have limits, but if nothing else, librarians might be able to set the table for conversations about how we all can encourage curiosity and develop in our students the itch to find stuff out. It's a practice, like writing, that matters.