You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Part One: Confession

I am a book person. I read a lot of them. I own a lot of them, and give a lot of them away I really like being in the stacks of my library, even though sometimes what I’m doing there is deciding which books shouldn't be there.

I am a book person who is dismayed that it’s getting harder to share scholarship through the medium of books. It’s not that we aren’t publishing enough books, it’s that we still – stupidly – demand books as a token of productivity exchangeable for the chance at a regular living wage even as the traditional infrastructure for making books public is crumbling. (Dear tenure and promotion committees: the answer to this problem is not to jack up the expectations. If you valued knowledge and learning, you’d never treat books this way. Knock it off.)

I’m a book person who frets about the excellent work that university presses do with dwindling support. They’re coming off the high of a post-war era when Americans thought paying taxes made sense and universities invested in books as a vehicle for the advancement of knowledge, but now value them primarily as tokens of productivity. Editors have to say “no” a lot because the books they publish have to sell enough copies to pay the bills. Sadly, libraries are no longer a primary buyer. If you look at Worldcat holdings, it’s as if a few years ago a zero got left off the number of libraries in the world holding any new academic book. That means the knowledge in these books has limited public circulation. Crafting a book that sells 300 copies when the same book might have sold 3,000 just a few years ago – well, the folks in this business who I know personally are smart and committed and not at all despondent, but I would have a hard time handling that, myself.

I am a book person who thinks the books a couple of my colleagues have published recently are fascinating and I wish people would read them. Hardly anyone will because the price tag for each is well over $100. Don't count on buying a used copy for cheap. To be used, you first have to be sold. These books were published by scholarly presses that are not university presses. The authors are happy to be published. They aren’t particularly upset that few people will read their books, because that’s not what scholarly books are for anymore.

This drives me crazy.

I am a book person who thinks curation is important and that we should not outsource to publishers and vendors the job of deciding what books are available at my library, which is how many libraries do it now with ebook packages. I don’t even think giving students a big catalog of electronic books, saying “go nuts!” while quietly paying the bill for whatever they choose to browse or download is a good plan even though it seems financially sensible. Paying $70 for a book we know someone wants is better than paying $70 for a book that may never be checked out. But I want to have books that we can share with other libraries through interlibrary loan, and I still believe in the idea that faculty and librarians should think about what to spend their limited resources on in ways that enable our curricular learning goals.Retaining some rights is nice, too.

I am a book person who thinks it’s time libraries did something about the future of books, because I’m one of those weirdoes who thinks books matter. Not old books. Not the idea of books. Not the smell of books. The scholarship inside the books. Books to be read. Books that do something to help us understand this world better.

Part Two: The Things We Do for Love

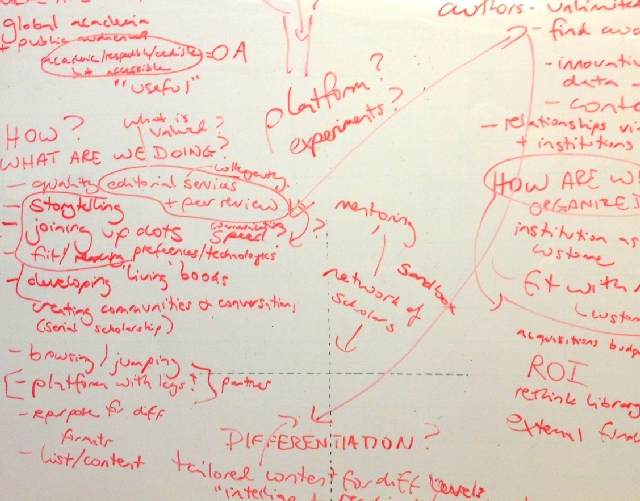

I’m looking at a picture I took of a whiteboard last week. It’s covered with jottings that are a partial record of a lively conversation held just before the annual meeting of Oberlin Group library directors at Rollins College. Some of us have windmill-tilting tendencies, and we've been working with consultant Melinda Kenneway, who is helping us decide whether and how we might pool our resources to start an academic press. Many of the libraries in the Oberlin Group contributed to funding this feasibility study. I don’t know if we will start a press, but the research we’re doing will be worthwhile, regardless. One of my fellow windmill-tilters, Bryn Geffert, found the faculty at Amherst College so impatient to start the revolution that they are starting a press without waiting for a collective approach, though Bryn remains deeply involved in the group effort.

We have developed some core principles and a lot of questions, which Melinda is helping us answer through a variety of means, including helping us clarify our assumptions and intentions, holding in-depth interviews with scholars, holding virtual workshops with library directors, and scanning the current environment for scholarly publishing. We are currently surveying faculty at some of our institutions and will probably extend to the survey to faculty at other institutions to get a broader sense of our potential authors and readers and what matters to them. Once we have looked at all the data, we’ll start thinking about logistics and funding models. And then we'll see.

Since we first started thinking about this project, all kinds of good things have been happening in open access book publishing. Maybe someone else will solve all the problems before we do. I’m optimistic, but I won’t sit still and wait for someone else to do the work, because I not only believe in books, I believe that the librarians and faculty at liberal arts colleges care about access to knowledge and have enough passion and intelligence to do more than shrug and hope things get better somehow. We’re makers. We’re doers. And we’re good at doing things that cross disciplinary boundaries without spending a lot of money because that’s how we roll.

We talked about supporting projects over a span of time rather than producing singular things (which I think bubbled out a reference I made to Doug Armato’s fascinating “serial scholarship” concept). We talked about authors’ desire for a sense of connection with editors who have the time to help develop projects and are good at getting the word out. We talked about the value of having an unlimited audience for scholarship and the potential to reach unexpected readers. We talked about the possibility of layering texts for different audiences so that a short, accessible piece might lead to a longer essay for a general audience with the full scholarly text as another layer, and data files and documents underpinning it all. We talked about short form books and multimodal texts. The things we talked about might not be even recognized as books by some definitions. We talked about being useful and about access to all.

There are a lot of arrows and even more question marks and mysterious things that only ring a faint bell a week later – what was the conversation that left that squiggle as its trace? But it was exciting to think about what could be, even if the how is going to be difficult, even if the results of our survey tell us that faculty mostly just want to be published, don’t care about access, and think librarians should get back to their proper work of buying stuff, which I suspect is how many librarians feel, too.

I’ve already had one friend tell me books shouldn’t cost too much, but they shouldn’t be free. Articles, sure, but not books. Having written a few of them myself, I understand the amount of work involved and the desire to have that work acknowledged, but scholarly books almost never repay even the tiniest amount of the labor involved in the form of money, and the payment of tenure to me is hollow and false (not to mention increasingly rare). Books could repay our efforts if people learned something from them, but that doesn’t happen if only a small group of people have the opportunity to read them. I keep coming back to that distinction Michael Polanyi made in "The Republic of Science." The freedom that scientists and scholars enjoy to decide which questions to pursue is not freedom for ourselves as individuals, it's a public freedom. Knowledge is a common effort for the common good. That's the only way it works.

As part of that common effort, one that I think librarians must participate in, I believe in the value of books and have faith that broader access to the ideas in them could make the world a better place.