You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

For the past three weeks, we have been exploring 15 Scenarios for the fall. The project began with a piece we published on April 15 called "The Low-Density University." That article was based on a proposal we made to our editor at JHU Press, Greg Britton, to work with him on a concise book using that same working title. Greg is our editor for our book Learning Innovation and the Future of Higher Education, which was published in February.

The central idea of The Low-Density University is that the pandemic caused by COVID-19 is forcing colleges and universities to rethink the entirety of their operations around the health and safety of their students, faculty and staff, as well as the communities in which they are located. As institutions look to resume residential education, the first question many schools are asking is “how many students are safe to bring back to campus, and when is it safe to do so?” Questions about academics, financial stability, operations, sports and co-curricular options follow, for many schools, from this principal question. Health and safety are intimately tied to density. In this context, then, density is a measure of the number of people on campus relative to physical spaces. These spaces on campus include classrooms and residence halls, as well as other places where students, faculty and staff congregate.

As we all know, target campus density levels under the pandemic are driven by social distancing guidelines. The farther students must sit apart from one another in a physical classroom, the lower the number of students that can attend a given face-to-face class session. The pre-pandemic campus density measure was high, with full classrooms and residence halls, as well as high-attendance campus events such as athletic competitions and performances. A low-density university is one that has transitioned from all remote instruction (no density), with some or all students back on campus, but with instructional and residential operations designed around social distancing guidelines.

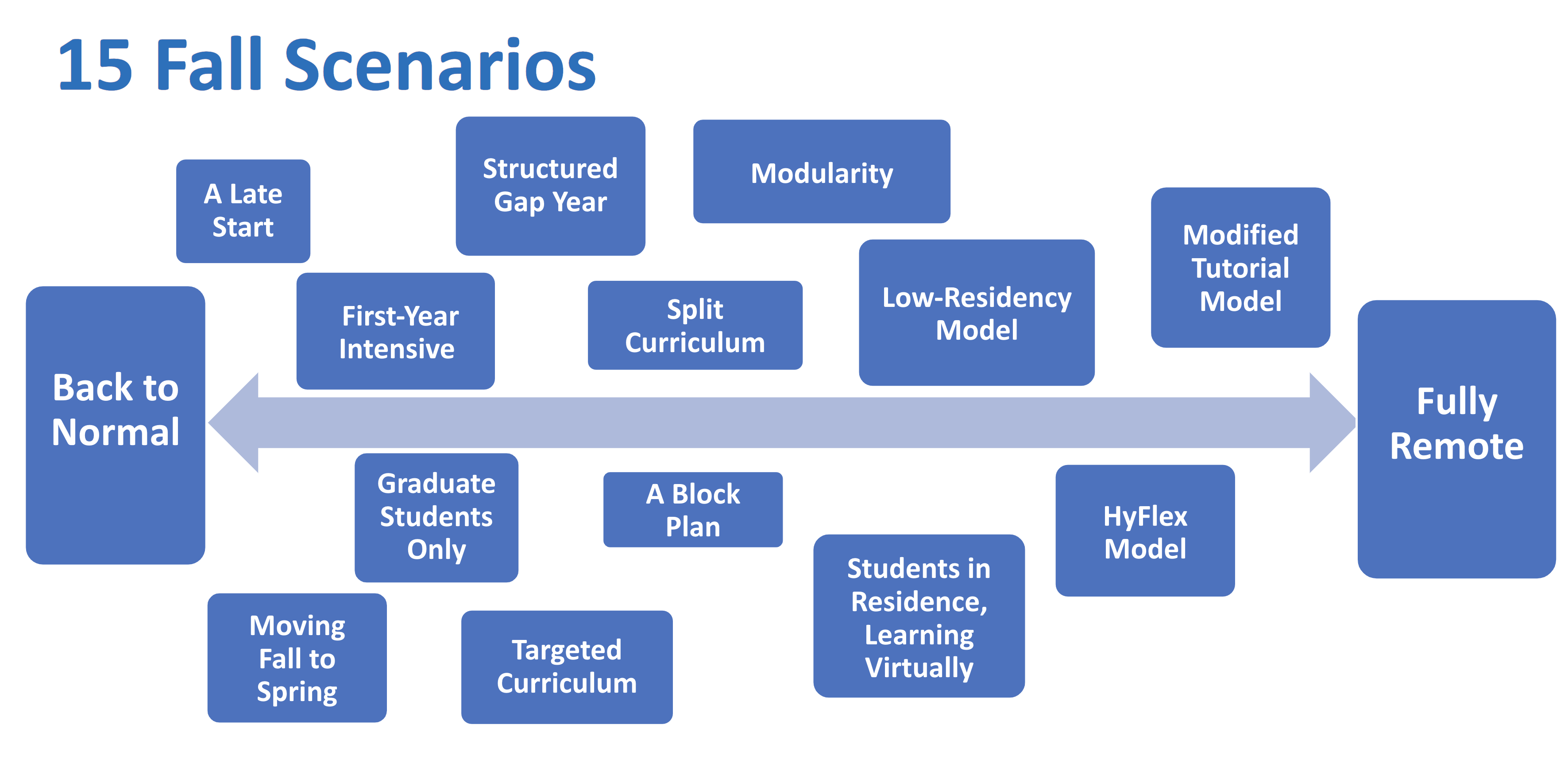

In writing "15 Fall Scenarios," our first goal was to develop a list of scenarios that could prove useful to colleges and universities trying to make sense of the educational and curricular possibilities under a requirement to reduce the density of their campuses. One way to think of each scenario is as an individual hypothesis for how colleges and universities might approach planning for the start of the 2020-21 academic year. The original list of scenarios had brief descriptions of a sentence or two to describe each one. For the next three weeks, we then published a more in-depth description of each scenario on each successive workday.

While each scenario stands on its own, the scenarios themselves can be placed on a continuum, bound on one end by Back to Normal, and the other end by Fully Remote. In between these poles are scenarios related to timing (A Late Start, Moving Fall to Spring, A Structured Gap Year), student population (First-Year Intensive, Graduate Students Only), curriculum (Targeted Curriculum, Split Curriculum, A Block Plan, Modularity), location (Students in Residence, Learning Virtually, A Low-Residency Model) and instructional method (A HyFlex Model, A Modified Tutorial Model).

Over the past three weeks, we’ve heard from schools about a variety of ways they have used these scenarios. On some campuses, the scenarios served as points of conversation and general ideas about how to approach fall planning. At other schools, the scenarios were explored one by one, with unlikely scenarios jettisoned while likely scenarios rose to the surface. And at still at other schools, they narrowed the discussion down quickly to two or three scenarios that seemed most likely for their campus. For many schools, the value of our piece was giving a name to the plans they were already considering. For others, it introduced some complexity to their thinking.

The interesting thing for us is just how different each school’s response was. In some cases, it seemed perfectly obvious that a modular approach was the right thing to do, but the idea of starting late was impossible to imagine. In others, the exact opposite -- starting late seemed the most ethical choice, while modularity seemed far too complicated to imagine pulling off. COVID-19 has shown that while all colleges and universities share many common traits, each has unique challenges and affordances based on a myriad of factors, from the financial to the geographic to the makeup of their community to the institutional structures and governance. Not quite Anna Karenina, but close.

We also have been hearing about how schools have been working to create their own version of a combination of scenarios. As we said in our original piece, these hypothesized scenarios were not intended to be either exhaustive or mutually exclusive. Indeed, it is entirely possible to derive hundreds, if not thousands, of scenarios for what higher education might look like in the fall of 2020. Schools interested in modularity may also be considering how a late start would affect the modules, while HyFlex approaches could be designed with first-year students on campuses. The best result for us is the way in which we’ve heard schools mix, match and modify the scenarios we described.

As we dived deeper into each scenario, we have tried to be careful to articulate both the reasons why a school might consider that option, as well as some issues schools may wish to consider. Of particular concern for us is the impact of each scenario on student access to, and equity within, a quality postsecondary education. The pivot from residential to remote education over the past few months has both revealed and amplified the inequalities embedded in the postsecondary system. The degree to which residential education helps bridge these inequalities was clarified by the pandemic-driven cessation of residential education. Where equality of educational opportunity never fully existed across the postsecondary ecosystem, it is also true that students from all backgrounds learned and lived in more or less similar circumstances when on campus. Everyone attended class in the same lecture halls, had access to the same academic libraries and, at least as freshmen, lived in the same residence halls.

With everyone now learning remotely, the goal that at least students who attend the same college or university should have a mostly similar educational experience has been more difficult to achieve. Students with dedicated access to newer computers, fast and reliable internet connections, and quiet places to study are at a significant advantage to students who have none of these assets. Student life professionals across the postsecondary ecosystem worked furiously to virtualize the web of academic, social and psychological supports that have evolved on campuses over the years. Despite their best efforts, however, the speed and scale of shift from residential to online learning have resulted in uneven success. Many students have been left behind. And while the true extent of the level of student disengagement and suboptimal educational outcomes during the weeks and months after the cessation of residential education can’t be quantified at this point, anecdotal evidence suggests that it is likely to be severe.

We will have more to say about these scenarios and our approach in the coming weeks, but we want to thank everyone who has shared their thinking about the fall, and their interest and their concerns about different choices their schools are considering. But most importantly, we’ve been humbled by the incredible goodwill the higher education community has shown at this moment. We are all trying to make difficult decisions in the face of an unprecedented, impossible situation. In every conversation we’ve had over the past month, we have been amazed at the resilience shown by the members of our community. We have challenges and things we need to work at. We need to find better ways to support our faculty and students during this incredible time. But because of the conversations we’ve had, we’ve felt even more optimistic about the future of higher education than ever before.