You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Last post I argued that human beings are central to education. This seems obvious to me and is additionally well-supported by research showing that the most important thing that can happen for a student is to work with a faculty mentor who takes an interest in their development.

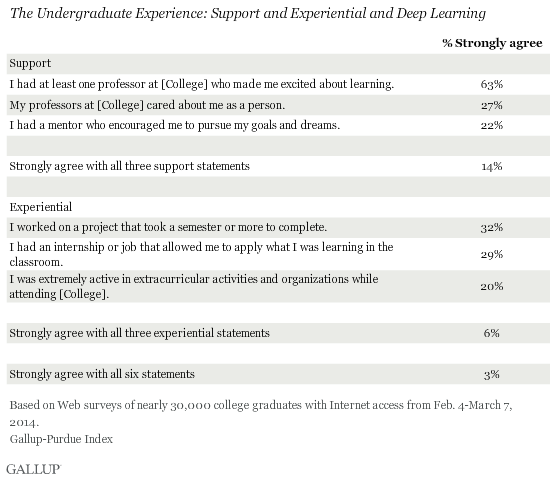

But the research also shows we aren’t necessarily all that good at it. The Gallup-Purdue survey of life after college shows that when asked whether or not students “had a mentor who encouraged me to pursue my goals and dreams,” only 22% “strongly agree.”

Only 14% of students report “strong” agreement with all three of the questions used to measure faculty support.

It’s also possible that when we do engage with students as mentors, our advice is either ill-informed, or even actively damaging. As one of my regular commenters, “Dennis,” says in response to the last post, “How many of the underpaid adjuncts who frequent this web site went to grad school because some teacher cared enough to say ‘Hey, you're really smart, you should get a PhD in . . .’ What great advice that was.”

Touché.

In a recent blog post, Cathy Day wrote about the “professionalization” of MFA programs, whether or not graduate studies should include instruction on preparing oneself for the market.

The problem is, as I’ve noted and Day reinforces, there is no academic market for MFA graduates. Day asks herself a series of questions, including: “If we put more MFAs on the job market with good materials, good applications, good credentials, are we making the adjunct crisis worse, or could we make it better?”

It’s a good question. I don’t think we know the answer.

I’ve never taught in an MFA program, but if I ever do, I believe one of my chief strengths would be the fact that I’ve both used my degree in a professional career outside of academia – as a marketing research consultant - and that I’ve managed to cobble together something that resembles a successful career as a working writer capable of self-support[1].

Today’s graduate students are going to have careers that look much more like mine than their faculty mentors that have successfully navigated the tenure track waters. Though, I’m not really sure how I’d translate these experiences into the classroom. My personal path is a combination of personal, purposeful, and accidental.

Do we need to add a course on taking advantage of lucky breaks or how to rebound from bad ones?

I wonder too about today’s undergraduate English major. No one is a firmer believer in the value of education (as opposed to training), and a literature degree not fully steeped in the traditions of literary studies hardly feels worthy of the designation, but do we have an obligation to arm our students with specific skills that will allow them to compete for jobs, something beyond “critical thinking” or “written communication?”

Should they know grant writing? How to design a WordPress site? Format a book in Adobe InDesign? What are the tangible skills they should exit with?

Those Gallup-Purdue metrics don’t actually have anything to say about content of courses or specific skills. It doesn’t seem to matter so much what we do, but how we do it and who we do it with.

The most meaningful experiences of my own education were largely accidental, serendipities of time and place. The communities I belonged to have had a much longer lasting impact than what I learned in any single course.

Still, I think we need to ask these questions, now more than ever. Are we doing right by our students?

What should they be learning? What do we have to teach them?

--

[1] This has entailed having to learn how to write a lot of different things and explore publishing well beyond the literary fiction I was immersed in during graduate school. My first book is done primarily in colored pencil. My second, has the word “fondling” in the title. You get the idea.