You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

At least with movies, the sequels rarely live up to the original.

A little over two years into the great “disruption” what, if anything, can we say about MOOCs now that the version 2.0s are here?

To find out, let’s go back to the future.

2012-2013 was called the “Year of the MOOC” by the New York Times. MOOC-related hype was everywhere. Expectations were high and outcomes were hard to predict. The courses were “experiments”—and producing them was exhausting.

I was part the team behind CopyrightX, an online course that debuted during the spring of 2013 against that backdrop. The endeavor stemmed from an ambitious collaboration among HarvardX, Harvard Law School, and the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard.

We set out to push the boundaries from the start.

First and foremost, we didn’t design a true MOOC. The course was large but not massive (“M”) and networked (i.e., it integrated online and offline experiences) rather than purely online (“O”). The seminar experience, not technology, lied at the heart of its pedagogy.

When gearing up for version 2.0, the context was different. We had more resources to draw on for the design process, like lots of valuable student feedback and data from last year, which has helped us to refine our teaching methods and materials.

And so the sequel for CopyrightX—AKA “The MOOC the New Yorker actually liked”—is underway, expanding and improving on its unique, hybrid format.

For version 2.0, in addition to the real-world classes attended by 100 Harvard Law students and online sections for 500 students, the course is adding more ‘satellites’ and integrating them more with the other two course communities. The satellites are, for the most part, “meat-space” classes (a blend of text and video chat) in about 10 locales around the world, each taught by an expert in copyright law.

Before I get ahead of myself, let me explain the basics: CopyrightX is a free and open networked course taught by Professor William Fisher of Harvard Law School that explores the current law of copyright and the ongoing debates concerning how that law should be reformed. Through a combination of pre-recorded lectures, weekly seminars, live webcasts, and online discussions, participants examine and assess the ways in which law seeks to stimulate and regulate creative expression.

While planning and running the first version last year, Fisher and the course team considered CopyrightX to be experimental. It was experimental in the narrow sense that we intended to test some hypotheses about learning law online. One hypothesis was that high-quality education in law must involve moderated small-group discussions of difficult issues. Another assumption was that non-lawyers could master the study of copyright law when taught in small groups.

To enable us to test these and other hypotheses, we limited enrollment to 500 students, all of whom were selected through an open application process. Admitted students were then assigned to discussion sections of 25 members, each of which was led by a teaching fellow who was a student at Harvard Law School.

We also divided our 500 students into four subgroups that differed based on the combination of reading materials and asynchronous discussion tools that they used. In order to receive a certificate of completion, participants had to satisfy a participation requirement and pass an exam.

Broadly, we conceived of the overall venture as a learning exercise (for everyone involved). We didn’t know, for example, whether students would be attracted to this rich but rigorous opportunity, and whether, once on board, they would commit to it.

At the end of the run, we felt that the inaugural version of CopyrightX was a success. Our assessment, however, was based on more than a feeling. We had data.

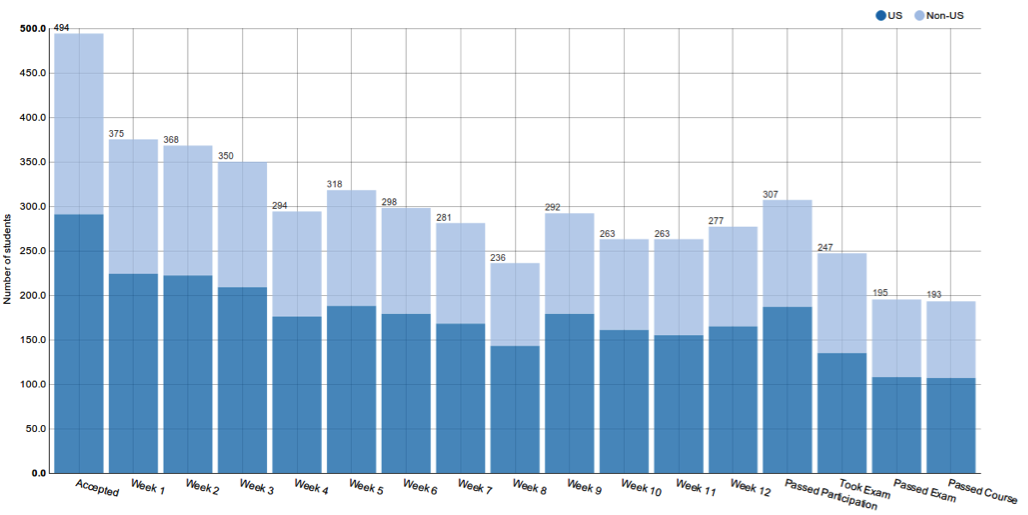

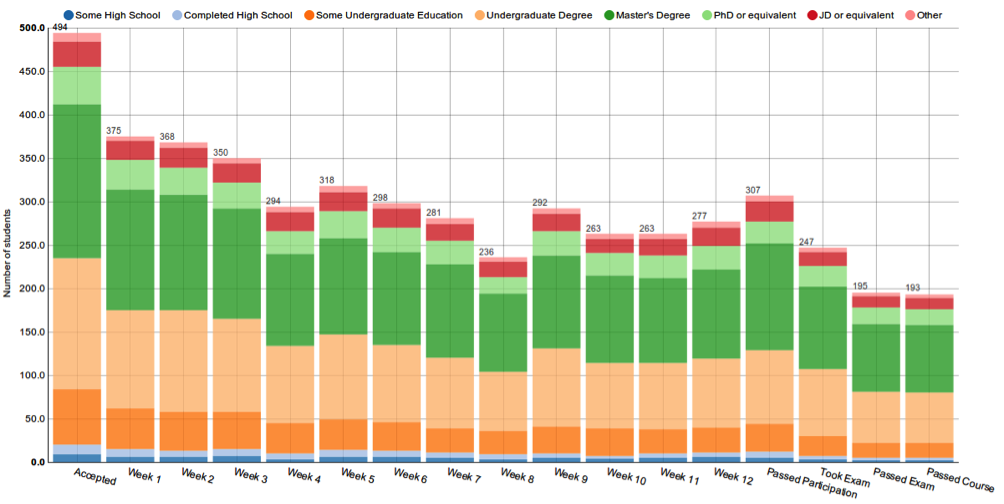

With regards to student retention, of the 500 admitted students:

- 277 (55.4%) attended the final meetings of their discussion groups;

- 307 (61.4%) satisfied the participation requirements set by the teaching fellows;

- 247 (49.4%) took the final examination;

- 195 (39%) passed the examination; and

- 193 (38.6%) both passed the examination and satisfied the participation requirement – and thus received a certificate of completion.

The following graphs illustrate more detailed information concerning participation and graduation rates for subgroups of students. The graphs show the number of students who accepted our offers of admission; attendance in the weekly Socratic discussion sections; the number of students who passed the course-participation requirements; the number of students who took and passed the exam, respectively; and the number who received a certificate of completion.

Graph 1: Participation By Country of Residence

Graph 2: Participation by Highest Educational Attainment

Some interesting comparisons lurk in these graphs. Consider the following juxtaposition of “graduation” rates (i.e., receipt of a certificate) and exam passage rates for various subgroups:

| U.S. | Non-U.S. | In high school | Finished high school | In college | B.A. | M.A. | Ph.D. | J.D. | |

| Graduation Rate | 37% | 42% | 22% | 27% | 27% | 38% | 44% | 42% | 68% |

| Exam Passage Rate | 80% | 78% | 66% | 75% | 74% | 75% | 82% | 75% |

82% |

Among the fruits of this comparison is that U.S. residents and non-U.S. residents do not differ materially on either dimension and graduation rates rise gradually with educational attainment. The exam passage rate, however, is remarkably consistent across groups.

Finally, our initial hypothesis that non-lawyers would be both willing and able to master copyright law finds support in these numbers.

As we prepare our second offering, we no longer consider CopyrightX an experiment. We’ve made several adjustments based on lessons learned from last year, but the overall structure remains the same.

When version 2.0 of the course launches in a few weeks, we will continue to organize students in discussion sections led by teaching fellows, but will aim to enrich the asynchronous discussion that takes place on discussion boards. In addition to real-time seminars, students will participate in moderated small-group discussion boards limited to their sections—“gardens”—that are closed, cultivated, and private. They will also have access to an unmoderated plenary discussion board—the “forest”—that is more unpredictable.

Notably, the second version of CopyrightX will also be more “networked” in the sense that it will integrate and connect three communities of students:

- a residential course on Copyright Law, taught by Prof. Fisher to approximately 100 Harvard Law School students;

- an online course including approximately 500 participants, divided into 20 “sections,” each taught by a Harvard Teaching Fellow; and

- approximately 10 “satellite” courses based in countries other than the United States, each taught by an expert in copyright law. (Satellite leaders’ bios are viewable here.)

Students in these three communities will engage with one another in the forest and during conversation of live-streamed special events with guest speakers.

At this point it looks like the sequel to innovative online courses, if done thoughtfully (and well), may be more work, not less, than first run, even if it is less experimental.

Does that mean that eventually we will “get it right,” in the sense that future versions will incorporate slight improvements every year at lower costs?

Quite frankly, I don’t know. What’s clear is that both on-campus courses and online ones can and should evolve. In the case of our course, we have no choice, as the laws of copyright change. So, pedagogy for copyright law should remain adaptable, even if it continues to value one teaching method that has lasted millennia, namely the seminar.

All of us involved with the course believe that transparency and openness about the lessons learned from our experiences may provide some basic building blocks for reflection and progress in pedagogy across many disciplines. With that in mind, the full report on the 2013 course is viewable: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/people/tfisher/IP/CopyrightX_Assessment.pdf

We plan to produce a similar report in 2014. In the meantime, whether you are enrolled in the course or not, we hope you tune in. We will be sharing updates about the course as it progresses at copyx.org.

Nathaniel Levy is a Project Manager at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University and a Lead Course Developer for HarvardX.