You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nearly 9,000 people, myself included, attended the annual conference of the Association of American Geographers (AAG) in late April 2015. The size of the conference has been growing over the last several decades and it has become a de facto international gathering despite the 'American' moniker; a trading space of sorts to present papers, share ideas, formulate collaborative research proposals, source prospective faculty, share gossip, have good times, etc. Of the 8,950 people who flew/drove/trained it to Chicago this April, 5,716 came from the US, 726 came from Canada, 666 from the UK, 257 came from China, and nearly equivalent numbers (35 vs 37) came from Singapore vs Mexico. All told, attendees came from 84 countries in total and they're mapped out below courtesy of my department's Cartography Lab. Needless to say this map highlights a highly uneven pattern of attendance with curiosities such as why are there so few geographers from nearby Mexico at the event, or why are more Canada-based geographers attending the AAG versus than annual meeting of the Canadian Association of Geographers (nearly 400 will be attending that event in lovely Vancouver shortly).

This year's AAG conference received a lot of very positive feedback (e.g., see posts by Jeremy Crampton and Rachel Squire) in part because of the nature of how well the event was organized, the scale of the event (the largest ever, meaning people are finally accepting it for what it is versus wishing it were a smaller & easy-to-manage gathering), and the iconic setting of downtown Chicago.

This year's AAG conference received a lot of very positive feedback (e.g., see posts by Jeremy Crampton and Rachel Squire) in part because of the nature of how well the event was organized, the scale of the event (the largest ever, meaning people are finally accepting it for what it is versus wishing it were a smaller & easy-to-manage gathering), and the iconic setting of downtown Chicago.

Coincidentally, in the weeks after the AAG conference, some interesting debates emerged about academic conferences more broadly, stirred up by Christy Wampole's 'The conference manifesto' (New York Times, 4 May 2015) - see here for two of these reactions:

- 'Save the Academic Conference. It’s How Our Work Blossoms' (Chronicle of Higher Education, 6 May 2015)

- 'A Conference Manifesto for the Rest of Us' (Inside Higher Ed, 15 May 2015)

Christy Wampole's response, appropriately titled 'Response to Responses to “The Conference Manifesto"' is worth a read too.

While the debate about Wampole's opinion piece is fascinating, if a little humanities-centric, I was more struck by the similarly timed debate about the impact of a mobile app (Twitter's Periscope) on the Floyd Mayweather Jr. vs Manny Pacquiao boxing match. See, for example:

- 'With Boxing Match, Video Piracy Battle Enters Latest Round: Mobile Apps' (New York Times, 4 May 2015)

- 'Twitter Has a Short-Term Periscope Problem. And a Long-Term Media Mess' (re/code, 5 May 2015)

- 'Twitter’s Periscope Disabled Dozens of Mayweather Fight Streams' (Bloomberg Business, 4 May 2015)

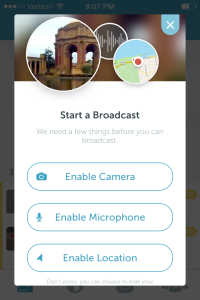

Periscope is a "teleportation device” - a mobile app that allows anyone to broadcast what they're experiencing, and anyone with a link to the stream to watch, for free.

Periscope is a "teleportation device” - a mobile app that allows anyone to broadcast what they're experiencing, and anyone with a link to the stream to watch, for free.

Now mobile phones were abundant at this year's AAG - I've never seen so many people wandering around like zombies, staring at their screens while almost tumbling down Hyatt Regency escalators. And the emergence of new apps like Periscope means that anyone at the next AAG annual conference (or any other conference for that matter, including the forthcoming #CAG2015 & the #RGSIBG2015) can stream keynotes, panel discussions, individual presentations, post session squabbles/debates, etc. Comments and color-coded hearts can be posted on streams, recordings and/or replays are possible, and so on. Are we all ready for this? I'm not so sure...

So, my preliminary read of things is this:

1) Most disciplinary associations are already behind the ball with respect to live streaming conference sessions, even keynote/plenary sessions, on platforms such as YouTube. Some keynotes or prominent panels are recorded and posted, though in highly variable patterns. In short, most academic associations lack the capabilities to strategically think through and adjust to the demand for live and on-demand video and audio (e.g., via SoundCloud).

2) Given (1), most disciplinary associations have limited capability to cope with what happened in the Floyd Mayweather Jr. vs Manny Pacquiao boxing match - individualized live-streaming, via mobile apps, of performances.

3) Faculty, postdocs and graduate students may, for good and/or bad, be increasingly live streamed in their sessions. Who knows, for example, who's just taking a photograph of a session or else live-streaming an entire talk. How will speakers message out their desire not to be recorded? Do associations need to "ask speakers to explicitly label if they don't want content tweeted" (or periscoped) or put symbols on slides "with data not for dissemination"? Will specialty groups, like the Economic Geography Specialty Group (EGSG) that I recently chaired, coordinate streaming of select sessions? Will/can/should these recordings be archived and assembled into a disciplinary-specific content repository, effectively morphing conference sessions into open educational resources (OERs) for use in courses?

4) The broader implications of mobile app-based streaming has yet to be thought through. If this phenomenon takes off will this open up access to conferences and better serve members of associations? Will this enhance or reduce prospective national and global demand to attend conferences once people see talks, dialogues, etc., including some like the sessions/conference practices critiqued by Christy Wampole in 'The conference manifesto'? Will streaming enhance access to sessions for those with limited resources to travel all the way to an expensive city like Chicago, and/or will it enhance anxiety re. missing out (assuming the streamed sessions are indeed high quality)? And will this phenomenon ramp up the use of Twitter in academia?

These are but a few preliminary thoughts on the potential implications of video streaming mobile apps for academic conferences. We're unlikely to see the same types of debates about video piracy as those associated with high profile boxing and other sporting events, but academics and our associations are not immune from the potentially unsettling/exciting dynamics of a sea of free 'teleporting technologies,' downloaded in mobile phones, digitizing our bodies, voices, and ideas, for anyone who has access to the associated feed.