You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Editors' note: today's guest entry, by Morshidi Sirat (Universiti Sains Malaysia), Norzaini Azman (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) & Aishah Abu Bakar (University of Malaya), is designed to provide you with an up-to-date and insightful summary of the state of the Southeast Asian higher education region-building project. Regionalism -- a state-led agenda to build up ‘regional coherence’ via the trading of goods and services, and the facilitation of human and non-human mobility (e.g. technologies, information, capital, the factors of production) – is a centuries old phenomenon. However, it was not until the Bologna Process (formally launched in 1999), which helped construct the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), that we witnessed the first substantial incorporation of higher education into regionalism agendas. For good and for bad it is also the Bologna Process that has helped stir up a series of subsequent ‘echoes’ (to use Pavel Zgaga's term) in other parts of the world regions' higher ed landscape.

For those of you interested in the theme of universities in a world of regions, please refer to this week's content in our MOOC Globalizing Higher Education and Research for the ‘Knowledge Economy.’ We're up to Week 4 of 7 as of Monday 14 April (see the syllabus here), though the course can be engaged with in a pick-and-choose method for the 'too busy' but curious of our readers. Apart from the text and visuals we provided this week, you’re very fortunate (we think!) to be able to listen to and read what a number of key players in higher education regionalisms think about the process. We have a podcast Q&A with one of the architects of the Bologna Process (Pavel Zgaga, former Minister of Education and Sport, Slovenia), as well as with a key player in the African Higher Education and Research Space development initiative (Goolam Mohamedbhai, Former Secretary-General, Association of African Universities). Taken together, all of this content should provide you with an up-to-date and insightful (we hope!) summaries of what is going on with respect to this fascinating, albeit complex, development process.

Our thanks to Morshidi Sirat, Norzaini Azman & Aishah Abu Bakar for their many insights below.

Kris Olds & Susan Robertson

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Towards harmonization of higher education in Southeast Asia: Malaysia’s perspective

by Morshidi Sirat (Universiti Sains Malaysia), Norzaini Azman (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) & Aishah Abu Bakar (University of Malaya)

Introduction

Harmonisation of higher education is essentially a process that recognises the significance of regional education cooperation and the importance of establishing an ‘area of knowledge’ in which activities and interactions in higher education, mobility, and employment opportunities can be easily facilitated and increased. It is the process that acknowledges diversity of higher education systems and cultures within the region, while simultaneously seeking to create a ‘common educational space’ (Wallace, 2000; Enders, 2004). A region in a supra-national context, with different cultures, religions, languages and educational systems, must develop a harmonised system of education so that it can foster a higher level of understanding, a sense of shared purpose and common destiny in a highly globalised world. This system could be developed or constructed on the basis of a common, but not identical, practices and guidelines for cooperation in education.

A common space or higher education area does not intend to create a uniform or standardised system of higher education. The primary goal is to create general guidelines in areas such as degree comparability through similar degree cycle and qualifications framework, quality assurance, lifelong learning, or credit transfer system and so on (Armstrong, 2009; Clark, 2007). These general guidelines will facilitate and smoothen international student mobility, lifelong learning, and hassle-free movement of talented workers within the region, which will strengthen regional economy in the long run. The regional higher education area is the space in which students, faculty members and HEIs are the key players promoting similar standards of higher education activities. In other words, in a region with a harmonised system of higher education there will be continuous interactions and mobility for students, faculty members and talents.

The most important factor that contributes to the success of the process of harmonisation in higher education is the participation and consensus building at the level of national agencies, the public and also other stakeholders. The key element of the harmonisation in higher education will be the establishment of a mutually accepted roadmap that will consist of a vision of future goal (such as the establishment of a higher education space/area), areas to develop common frameworks (identified by key stakeholders such as credit transfer system, quality assurance guidelines, regional qualifications framework or comparable degree cycle and so on), methods and the key players who will be responsible for framework development and information dissemination to the public. According to Hettne (2004), harmonization is cyclical, and a policy process (functional cooperation) and policy tools (lesson-drawing, policy externalization, and policy transfer) anchors it.

Harmonization in Southeast Asia

The idea of harmonizing higher education systems in Southeast Asia was inspired by the development of regionalism in higher education in Europe, specifically the establishment of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). The idea of regionalism in higher education in Asia or Southeast Asia is a very exciting idea, indeed.

Southeast Asia has been integrating rapidly mainly through trade and investment. The region is also witnessing increasing mobility of people in the region and between regions. This new context places higher education in a pivotal role in developing human resources capable of creating and sustaining globalized and knowledge-based societies. Harmonizing the highly diverse systems of higher education in the region is seen as an important step towards the regional integration objective. The most common measure is the step towards a greater degree of integration in higher education policies and practices through concerted regional efforts.

Regionalization of higher education has political, economic, social and cultural dimensions, similar to globalization (Terada, 2003; Hawkins, 2012). As a political lever, regional cooperation provides opportunities for regions and individual nations to contribute to international quality assurance policy discussions. As an economic lever, regional integration provides smaller higher education systems entrance to possibilities of competition and cooperation on an international or regional scale. As a social or cultural lever, regional activities build solidarity among nations with similar cultural and historical roots (Yepes, 2006). Therefore, higher education regionalization looks differently, depending on the dimensions, actors, and values involved in the process.

In recent years Southeast Asian countries have shown commitment towards deepening connections and interactions by looking at the rich regional diversity as important basis for regional cooperation and collaboration rather than as stumbling block. It is envisioned that the ASEAN Community 2015 would be the outcome of cooperation and collaboration in ASEAN in areas relating to regional understanding and economic integration. ASEAN, as a regional block comprising of 10 nations, namely, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, is steadily moving towards achieving “One Vision, One Identity, One Community” aspiration by 2015.

ASEAN leaders set a vision to build an ASEAN Community with three building pillars: the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC), and the ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC). The primary goal of ASCC is create an ASEAN Community that is people-centred and socially responsible based on shared values.Education, particularly higher education has been treated as the core action line in promoting the ASEAN-Socio Cultural Community and in supporting the continued economic integration of ASEAN by 2015. Higher education in the region has been mentioned in many official declarations as one of the important steps to enhance human resource development in the region. An ambitious plan was set up in 2009, aimed at creating a systematic mechanism to support the integration of universities across Southeast Asia. Student mobility, credit transfers, quality assurance and research clusters were identified as the four main priorities to harmonize the ASEAN higher education system, encompassing 6,500 higher education institutions and 12 million students in 10 nations.

The ultimate goal of the plan is to set up a Common Space of Higher Education in Southeast Asia. The strategic plan calls for the creation of the ASEAN area of higher education with a broader strategic objective of ensuring the integration of education priorities into ASEAN’s development. The education objectives aim to:

- advance and prioritize education and focus on: creating a knowledge-based society;

- achieving universal access to primary education;

- promoting early child care and development; and

- enhancing awareness of ASEAN to youths through education and activities to build an ASEAN identity based on friendship and cooperation as a key way to promote citizens’ mobility and employability and the continent’s overall development.

The declaration advocates specific reforms focusing on a harmonization in the higher education system with the objective of increasing the international competitiveness of ASEAN higher education.

Since then, individual ASEAN governments have increased public investment in universities to support the ASEAN Higher Education Area, and the region’s burgeoning knowledge economy. Measures have been set up to strengthen the performance of Southeast Asian universities across a wide range of indicators such as teaching, learning, research, enterprise and innovation. These initiatives also pave the way for further collaboration and integration between universities in the region, enhancing the overall reputation of ASIAN universities compared to their competitors in the West and elsewhere in the world. It is not surprising to see the improved performance of many ASEAN universities in this year’s QS University Rankings: Asia.

As one of the five founding members of ASEAN, Malaysia has played a very active role in the organisation with ideas and initiatives that has contributed to shaping ASEAN into what it is today and what it is going to be in the future. Malaysia also initiated in the of ASEAN Plus Three summit, namely ASEAN and China, Japan and South Korea, which was the other name in replacement of the East Asia Economic Caucus (EAEC) for the East Asia Summit (EAS). Malaysia has also taken a leadership role in the harmonisation of the higher education systems through many initiatives. For example, the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) played a crucial role of promoting harmonisation by encouraging active movement towards the development of quality assurance collaboration and sharing. The MQA spearheaded the establishment of the network of quality assurance agencies among Southeast Asian Countries, known as ASEAN Quality Assurance Network (AQAN). It was introduced to develop and recognize strength and commonalities in academic practices without losing individual country identity apart from ensuring compatibility of qualifications and learning outcomes within the ASEAN countries.

Benefits/Advantages

Admittedly, there are benefits in creating a common higher education space in Southeast Asia. The more obvious ones are greater mobility, widening access and choices, academic and research collaborations, enhanced collaboration on human capital investment, and the promotion of ASEAN and/or Southeast Asian within the fast changing global higher education landscape. The immediate advantage of such harmonization in higher education system is presented as easier exchange and mobility for students and academics between nations within Southeast Asia apart from member countries availability to access systems, tools and best practices for quality improvement in higher education. For some countries, harmonization serves as a jump start for keeping up with globalization

Arguably, the model that is most desired and considered most feasible is that which does not require all higher education systems to conform to a particular model. The general consensus is that a system that become a reference or one that can be fitted into without jeopardizing cultural diversity and national identity is considered most feasible and desired. This consensus is very much in line with the successful approach used by the early Muslim scholars where their methodology involved taking all ideas which were non-contradictory to their religious value and faith. The scholars only borrowed ideas from others but they went on further to expand and introduce innovative ideas (Abbas, 2011). This approach has led to development of unique learning culture, which is the basis of a stronger community. As a result of harmonization, differing national standards come closer together. However, it has been very difficult for nations to agree on common standards mainly because issues of sovereignty usually become points of contention and also because it is not, in itself, an easy process. In the recent discussion with other ASEAN country members at the ASEAN + 3 meeting, Malaysia has recommended the idea of finding commonalities in practices when developing standards and not imposing uniformity and that such initiative should be undertaken in stages taking into consideration the various level of higher education development in ASEAN.

Forms of Harmonization

The likely scenarios of higher education landscape in Southeast Asia as a result of such a harmonization of higher education systems are generally perceived as follows:

- Students from different countries spend at least a year studying in other countries

- Students in different locations are offered the same quality of education regardless of higher education institutions

- Graduates from one country are recruited by the employment sector in other countries

- A multi-national workplace

- Close collaboration between faculty in creating and developing new knowledge

- Close collaboration between students in creating and developing new knowledge

- Close collaboration between employment sectors in creating and developing new knowledge

- Larger volume of adult students in the higher education system

- Close collaboration between International Relations Offices who are the key player behind mobility program.

Plan of Actions

The following actions are deemed necessary in achieving the desired goal in harmonizing higher education among ASEAN community:

1. Regional Accreditation

Accreditation is very important in higher education. It is viewed as both a process and a result. It is a process by which a university/college or technical and vocational training institution evaluates its educational activities, and seeks an independent judgment to confirm that it substantially achieves its objectives, and is generally equal in quality to comparable institutions. As a result, it is a form of certification, or grant of formal status by a recognized and authorized accrediting agency to an educational institution as possessing certain standards of quality which are over and above those prescribed as minimum requirements by the government.

2. Unified Education Framework

Intergovernmental Organizations establish ASEAN standards for HEI’s including curriculum. Consequently, revising curriculum and delivery modes in all programs are still on the process to meet labour market needs. Thus, a unified curriculum in the ASEAN region is highly recommended to achieve the desired goal of one community. The focus should be on learning outcomes.

3. Improve Quality of Education

ASEAN countries need to improve the quality of their education systems as many graduates lack the skills needed in today's rapidly changing workplace. The shortage of skilled workforce in the Asia-Pacific Region, male and even more so female, has been a major bottleneck in economic and social development. There is a need for greater emphasis on technical and vocational education and training (Liang, 2008; Kehm 2010).

4. Scholarship for students/Faculty Exchange

More programs on scholarships grant on students from all the regions are now being practiced in most ASEAN countries. The Scholarships aim to provide opportunities to the young people of ASEAN to develop their potential and equip them with skills that will enable them to confidently step into the enlarged community. Another medium of attaining the quality of education is by educating the teachers, academics and other educational personnel and upgrade their professional competency. Programs can be introduced that focus on talent management, leadership selection and review of teachers’ and lecturers’ workload. Various initiatives, from faster promotion prospects to awards can be introduced, to acknowledge the role teachers and academics play, and raise the image and morale of the teaching and academic profession.

5. Regional Skills Competition

Encourage the participation of higher education institutions and TVET institutions in skills competitions such as the ASEAN Skills Competition to support workforce development and to achieve regional standards competency. It will contribute towards the advancement of quality and skills of workers in all ASEAN Member Countries.

6. Increase Usage of English Language

Language is a key towards the development of a global community. Workers should realize the importance of being able to communicate in English as an important tool for the realization of ASEAN Community 2015 so that they will not face a handicap to benefit from the fruits of the ASEAN community.

Key Actors, Activities, and Progress

Over the past years, regional bodies have emerged as new and key actors in higher education policy making, offering the possibility of higher education regionalization (Wesley, 2003, Hawkins, 2012). Regional bodies introduce a new level to the local, national, and global spectrum of higher education policymaking and practice. Regional bodies can provide a smaller venue for national organizations to collaborate on norm-setting and policy harmonization that relate specifically to regional needs, values, and identity (a national-to-regional trend). Regional bodies can also give voice to smaller developing countries that do not have the economic status or ability to participate in international policy making discussions (a national-to-regional-to-international trend). Likewise, regional bodies have the potential for grassroots initiatives to gain a broader audience (local-to-regional-to-international trends) (Wesley, 2003, Hawkins, 2012). It is against this background that this paper turns to initiatives taken by regional bodies in their roles and activities in harmonizing the higher education sector in Southeast Asia.

In Southeast Asia,the status of integration of higher education in ASEAN are being studied and promoted by three main bodies namely SEAMEO RIHED, ASEAN Plus Three and the ASEAN Universities Network (AUN). Their aim is to promote education networking in various levels of educational institutions and continue university networking and enhance and support student and staff exchanges and professional interactions including creating research clusters among ASEAN institutions of higher learning. Further actions are envisaged to strengthen collaboration with other regional and international educational organizations to enhance the quality of education in the region. Higher education systems in Southeast Asia are very diverse, and even within each nation incompatibility is to be expected. But, it is important to appreciate that in the context of Southeast Asia, with its diverse systems, harmonization is about comparability; not standardization or uniformity of programs, degrees and the nature of higher education institutions.

ASEAN Plus Three

Beginning in 1997, the ASEAN community began creating organizations within its framework with the intention of achieving their goals. ASEAN Plus Three was the first of these organizations and the network was designed to improve existing ties with the People's Republic of China, Japan, and South Korea. ASEAN Plus Three developed a Plan of Action on Education: 2010-2017 which emphasizes the need to develop and implement strategies related to quality assurance and the promotion of mobility. Subsequently, the ASEAN Plus Three Working Group on Mobility of Higher Education and Ensuring Quality Assurance of Higher Education among ASEAN Plus Three Countries was created. The working group main objectives are to analyze credit transfer systems within the ASEAN Plus Three region, and explore ways to improve student mobility programs in the ASEAN Plus Three region.

SEAMEO-RIHED

The Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) is an international organization established in 1965 among governments of Southeast Asian countries to promote regional cooperation in education, science and culture in Southeast Asia. Members of SEAMEO included Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Socialist Republic of Vietnam. SEAMEO-RIHED (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization - Regional Centre for Higher Education and Development) was later developed under the umbrella of SEAMEO working for 10 Member Countries in Southeast Asia. Specifically, its mission is to foster efficiency, effectiveness and harmonization of higher education in Southeast Asia through system research, empowerment, development of mechanisms to facilitate sharing and collaborations in higher education (Yepes, 2006; Nguyen, 2009). Programs under SEAMEO-RIHED mainly serving 5 objectives

- Empowering higher education institutions: includes Study Visit Programmes to the US, the UK, Australia and China, training courses for International Relation Offices (IRP) in Southeast Asian HEIs and workshops on governance and management for HEIs.

- Developing harmonization mechanism: includes internationalisation Award (iAward), workshops on Academic Credit Transfer framework from Asia and Southeast Asian Quality Assurance Framework.

- Cultivating Globalized human resources : includes the ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) Programme.

- Advancing knowledge frontiers in higher education system management: includes Policy Action Research: Building Academic Credit Transfer Framework for Asia.

- Promoting university social responsibility and sustainable development : include seminar on University Social Interprise.

Out of the five objectives, the main focus being cultivating globalized human resources through AIMS students’ mobility program in which the Malaysian Education Ministry under the Department of Higher Education is directly and actively involved. It also includes the iAward program where Malaysia has participated under AIMS previously known as Malaysia-Indonesia-Thailand (M-I-T) Student Mobility Project.

AIMS Program

Student mobility has always been one of the key strategic elements of cooperation leading to the development of a harmonized higher education environment among countries in Southeast Asia. The ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) program commonly known asAIMS was started in 2009 to aid the drive towards European higher education harmonization. This program was designed to encourage student mobility through the multilateral collaborations among four countries: Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Three objectives formed the reasons behind the promotion of student mobility and greater university cooperation:

- enables students to hone their academic skills and intercultural understanding,

- provides the critical knowledge needed to succeed in today’s globalised economy,

- promotes regional cooperation between higher education institutions and helps to produce the international graduates that are attractive and necessary for an intergrated ASEAN Community to contribute to the development of qualified, open-minded and globalized human resources.

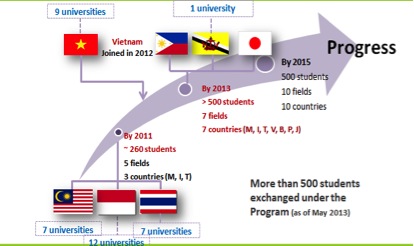

According to a report prepared in 2013, on the first three years of AIMS, the number of students participating in AIMS grew from a total of 260 students in 2011 to more than 500 students in 2013. The five disciplines involved were Hospitality and Tourism, Agriculture, Language and Culture, International Business and Food Science and Technology. Two additional disciplines were included in 2013 which are Engineering and Economics.

The implementing partners are:

- Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia;

- Directorate General of Higher education, Ministry of Education and Culture (DGHE, MOEC), Indonesia;

- Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education (OHEC, MOE), Thailand; and

- Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Education and Training, Vietnam, recently joined in 2012.

The AIMS Program targets an expansion (set in 2009) as below.

| By 2011 | By 2013 | By 2015 |

| 150 students | 300 students | 500 students |

| 5 study fields | 7 study fields | 10 study fields |

| 3 countries | 5 countries | 10 countries |

The program aims to make temporary student mobility as a regular feature of higher education in Southeast Asia, as dedicated academic and administrative measures for internationalization of students’ experiences are generally viewed as essential for dynamic institution of higher education. As of December 2013, the progress of AIMS program is as shown in the diagram below.

(Source : Student Mobility: focusing on the globally competent human resources, Li Zhe (2013) presented at the First Working group on Mobility of Higher education and Ensuring Quality Assurance of Higher education Among ASEAN plus Three Countries, 30 September 2013, Tokyo Japan )

From the above projection, AIMS welcomes new members and the decision to join AIMS must come from the ministry responsible for higher education. The process for joining AIMS involved contacting RIHED, observing AIMS Review Meeting, reviewing AIMS handbook, assigning AIMS contact person, identifying participating HEIs, organizing In-country initiation meeting, allocating budget, organizing and attending policy meeting, attending further AIMS review meeting and consulting on student visa procedure (ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) Program – Operational Handbook page 9-10).

So far, AIMS program has only involved undergraduates at degree level of any year in the program from fields of study (disciplines) that were determined collectively by participating countries. The duration of the mobility program awarded by Ministry is a minimum of one semester, but not more than six months. The undergraduate students that participate in AIMS are funded by each respective government. The HEIs involved in the AIMS program are nominated by the respective education ministries. Only flagship and leading universities are selected to aid credit transfer, matching of course syllabi, accreditation and attracting students to join the programs. The number of students involved in the exchange programs and the administrative arrangements of the AIMS is made through the HEIs bi-lateral agreements. However, while the AIMS Program marks the emergence of student mobility in ASEAN higher education institutions, it is the issue of recognition of periods of study and the recognition of academic qualifications obtained in another country that became highlighted and needed further review.

In ensuring the effectiveness and sustainability of the AIMS program, semi-annual review meetings involving the government agencies and HEIs representatives from member countries are carried out each year. The review meeting updates member countries on the development of the program, shares experiences and good practices, exchanges policy making and verifies student mobility data, foresight, plan and arrangement for future mobility activities.

The Internationalization Award (iAward)

The Internationalization Award was established in the year 2012 to recognize the contribution and significance of the international Relation Office as a focal point for students exchange in mobility programs. It recognizes universities that are making significant, well-planned, well-executed, and well-documented progress toward student mobility activities especially those using innovative and creative approaches. In addition, the iAward was aimed to serve as an assessment tool for the AIMS Program as well as a mechanism for quality assurance of internationalization. The specific objectives are:

- To promote good practices in internationalization by International Relations Offices (IROs); and

- To provide a collaborative atmosphere for experience sharing.

The process of iAward involves each ministry to nominate at least 2 IROs from their country. The nominated IROs are required to submit a self-assessment report before a site visit assessment is carried out by the iAward Assessment Committee. The award is granted to IROs that has demonstrated a commitment to the internationalization of student experience through one or more of the criteria listed below:

- The establishement of a system assessment (planning, controlling & follow-up)

- The establishment of facilities & infrastructure

- Excellence in services and feedback

- Excellence in governance, organization, staff

iAward assessment measured three dimensions of inputs (the resources available to support IRO efforts); outputs (the work and activities undertaken in support of mobility) and outcomes (the impact and end results).

The three recipients of the 2012 were the Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia; BINUS University, Indonesia; and Mae Fah Luang University, Thailand. The recipients were invited to present their good practices and experiences to participants from 7 countries at the 5th Review Meeting of the ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) Program. They highlighted initiatives that remove institutional barriers and broaden the base of participation in international mobility programs.

There are a number of challenges that the AIMs need to look into. The program is rapidly expanding from three countries in 2010 to seven countries in 2013 and this presents logistical challenges to the management of the next phase of iAward assessment. This scenario is expected to get worst in the future if all the 36 universities participate actively in the program. This would mean that the applicability of the concept of one award per country will have to be reviewed.

As the number of students increases, the AIMs needs to move their focus on numbers and percentages of students involved in each country to the content and quality of the regional experience. After all, student mobility and internationalization of higher education as such is not a goal in itself but a means to enhance the quality of the educational experience and the international learning outcome of the students.

The ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework

In order to facilitate student mobility, the region’s diverse higher education systems need more harmonized standards and mechanisms for permeable and transparent quality assurance and credit transfer among institutions. Encouraging and supporting students to study abroad is a major strategy to develop a well-trained regional workforce, which can improve the quality and quantity of human resources in the ASEAN economy as well as the national education sector.

The ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework (QRF), a common reference framework, functions as a device to enable comparisons of qualifications across participating ASEAN countries while at the same time, support and enhance each country’s national qualifications framework or qualifications systems that are currently at varying levels of development, scope and implementation. The ASEAN QRF addresses education and training sectors and the wider objective of promoting lifelong learning. The framework is based on agreed understandings between member countries and invites voluntary engagement from countries. Therefore it is not regulatory and binding on countries.

The ASEAN QRF aims to be a neutral influence on national qualifications frameworks of participating ASEAN countries. The process for endorsing the ASEAN QRF is by mutual agreement by the participating countries. Countries will be able to determine when they will undertake the processes of referencing their qualification framework, system or qualification types and quality assurance systems against the framework. The purpose of the ASEAN QRF is to enable comparisons of qualifications across countries that will:

- Support recognition of qualifications

- Facilitate lifelong learning

- Promote and encourage credit transfer and learner mobility

- Promote worker mobility

- Lead to better understood and higher quality qualifications systems. (AQRF, 2013)

Currently chaired by the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA), the ASEAN QRF will also provide a mechanism to facilitate comparison and transparency of and harmonise regulatory agreements. It will link the participating ASEAN NQFs or qualification systems and become the ASEAN’s mechanism for recognition of its qualifications against other regional and international qualifications systems.

To promote quality assurance of education and training across the region, the ASEAN QRF is underpinned by a set of agreed quality assurance principles and broad standards related to:

- The functions of the registering and accrediting agencies

- Systems for the assessment of learning and the issuing of qualifications

- Regulation of the issuance of certificates.

The ASEAN QRF utilises the East Asia Summit Vocational Education and Training Quality Assurance Framework quality principles, agency quality standards and quality indicators as the basis for the agreed quality assurance standards. The East Asia TVET Quality Assurance Framework is to be used as the benchmark for evaluating the quality assurance processes (for all education and training sectors). The referencing process will include member countries referencing their education and training quality assurance systems against the East Asia Summit Vocational Education and Training Quality Assurance Framework (AQRF, 2013).

A board or managing committee was established by the ASEAN Secretariat for the maintenance, use, evaluation and review of the ASEAN QRF, including a mechanism for assessing whether the Framework is providing the enabling function for member countries. The board or managing committee responsible for the on-going management of the ASEAN QRF is to be made up of national representatives (from a NQF or responsible body) in each country and an independent expert. The board or managing committee shall also be tasked with providing a central repository for member country referencing documents, and with providing access to information and guidance to other countries external to the ASEAN region on the ASEAN QRF.

Based on the current status, the development of a comprehensive ASEAN QRF still has a long way to go. To move forward, there is a need to identify major obstacles including reaching a mutual understanding between the “sending” and the “receiving” countries and identifying key players to be in the taskforce. It requires strong and long-lasting commitment by the participating countries and entails strong collaborations within and across Ministries, and other stakeholders in the participating countries. Nevertheless, there have been significant steps towards an ASEAN QRF that will facilitate student and labour mobility in the region.

Credit Transfer System (CTS)

To date, there are two attempts at developing a credit transfer system in Southeast Asia. The first is by University Mobility in Asia and the Pacific (UMAP), a network of voluntary association of government and non-government representatives of the higher education (university) sector in the region. UMAP’s major contributions to the formation of a harmonized regional approach to HE in the Asia region was the development of the University Credit Transfer System (UCTS), a mechanism to satisfy one of the key concerns of most proponents of a regional approach to higher education (mobility for students seeking transfer of credits within the region). Founded in 1994 with 35 countries and over 359 HEIs members, UMAP hasdeveloped a trial programme to promote student mobility in Asia Pacific. Similar to other endeavours in many parts of the world, the UCTS aims at creating a more sustainable mobility programme that enables students to earn credits during their studies in other universities. According to the UMAP, host and home universities are required to complete a credit transfer agreement in advance of the enrolments, both at graduate and post-graduate levels. Participating universities are now voluntarily taking part in the trial process of implementing the UMAP Credit Transfer Scheme (UCTS). According to Nyugen, 2009, very few institutions have utilized UCTS and know what the system is all about (in Japan, a major proponent of receiving students from Asia, had only 6 percent of their HEIs utilizing UCTS as a tool). She notes that the program has a lack of identity in the region as well as financial support.

Somewhat more successful in terms of usage is the ASEAN University Network’s (AUN) credit transfer system known as ASEAN Credit Transfer System (ACTS). AUN was established by ASEAN in 1995 to embark on a program of strengthening relations and activities among higher education institutions. As of 2011, it had about 26 members. According to ACTS, credit transfer is the award of credit for a subject in a given program for learning that had taken place in another program completed by a learner prior to the program he/she is undertaking or about to undertake. When the institution recognizes that a subject or a group of subjects that have been completed at a different institutions equivalent to the subject or a group of subjects in the program that the student is about to undertake, the credit from the subject or group of subjects is transferred to the program the student is about to undertake. The equivalence between the subjects completed prior to the subject to be taken by the student is assessed based on the credit value, the learning level and the learning outcomes of the two subjects in question (Asia Corporation Dialogue, 2011).

While the ACTS is opened to all HEIs in the region, the fact is it has become primarily an elite program, as “elites prefer to cooperate with elites” (Nguyen, 2009, p. 80). Therefore, it is somewhat self-limiting (Hawkins, 2012). More interesting was the AUN sub-regional networking on QA practices, which seeks to establish some common standards for the region. In particular, the AUN Quality Assurance program has the goals of enhancing education, research and service among its members. AUN-QA complemented with a set of guidelines and manual for implementation reaches out to all institutions in the region that wish to get the AUN-QA label. In the last decade, AUN-QA has been promoting, developing, and implementing quality assurance practices based on an empirical approach where quality assurance practices are shared, tested, evaluated, and improved.The AUN-QA activities have been driven through increasing collaboration among its member universities but also with ASEAN Quality Assurance Network (AQAN), SEAMEO-RIHED, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA). The collaborations efforts are expected to further hasten the harmonization of AUN-QA framework within and outside ASEAN.

Challenges

The implementation of the harmonization idea is not without challenges. Steps should be taken in order to increase student readiness. Barriers to language and communication must be overcome and there should be serious efforts to reduce constraints that are very ‘territorial’ in nature. Admittedly, students involved in mobility program may be faced with adjustment problems particularly with respect to instructional practices, curriculum incomparability, and cultural diversity. Then there is the language problem: differences in languages post a great barrier for inward and outward mobility of students at the macro level. ‘Territorial’ constraint, whereby each country hopes to safeguard the uniqueness of their educational programs, which in turn, may ultimately constrain the implementation of regional harmonization efforts, is a major consideration to be factored in.

Generally, the stakeholders have favorable views regarding the credit transfer system for ASEAN. Nevertheless, there is the issue of quality as the role of AQA (ASEAN Qualifications Agency) as a reliable monitoring body is being questioned. The AQA needs to exist and links need to be built between the different national quality assurance systems. The number of significant issue associated with quality assurance would require resolution facilitated by the AQA so that the local, regional and national autonomy is not compromised by external credit system. However, ASEAN needs a system that guarantee the quality of credits associated with education gained under any national system. Most importantly, mutual trust and confidence between different systems have to be developed. Without more transparency and knowledge about the quality of each other’s system, the development of credit transfer system within ASEAN will be very slow.

In the context of the cooperation in QA, the region still possesses a few structural impediments, the most important one being the problem about disparity of QA development. One could not argue differently that the level of disparity of HEIs and QA development in this region is extremely high. It could be said that the current stage of QA development in Southeast Asia is more or less similar to those in other developing countries in a sense that most of the QA systems have been originated by or operated as national formal mechanism. Half of the countries in the region, including Cambodia (ACC), Indonesia (BAN-PT), Malaysia (MQA), Philippines (AACCUP, PAASCU, etc.), Thailand (ONESQA) and Vietnam (Department of Education Testing and Accreditation) have national QA systems operated either under the umbrella of the MOEs or partly funded by the government. Although the majority of Southeast Asian countries in this region have already established and developed their national QA mechanism such as Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, the rest is still in the stage of developing quality assurance infrastructure such as Myanmar, Cambodia and Lao PDR. Such disparity has fundamentally contributed to the inefficiency in developing a formal or common QA cooperation within the region. However, this does not mean that Southeast Asia could not do anything to promote mutual development of QA systems within the sub-region.In fact, it has developed the ASEAN Quality Reference Framework as a guideline for effective quality assurance mechanism.

ASEAN countries are rich in culture, diverse in language and religion but have one common goal, to be united as one. Mostly, the language barrier has always been a constant problem among the people of the member countries. This is a great challenge to the ASEAN Community to further create programs on how to address this issue. The increase of usage of English language is one of the focal areas to be considered.

Regardless all those differences, Southeast Asia countries share a similar emphasis on human resource development as a key in developing the whole nation to enter the knowledge-based economy and global environment. It is realized that they are moving fast forward the situation in which all nations operate in a global market environment. In so far as Malaysia is concerned, it has to be recognized that harmonization is not about ‘choice’. It is a global movement that now necessitates the involvement of all Malaysian higher education institutions. There are benefits to the private players. Initially, we need a state of readiness at the macro level, whereby the aims and principles of harmonization have to be agreed upon by all stakeholders and players in the local higher education scene.

Conclusion

The drive toward harmonization of ASEAN higher education seems to be on track, and member signatories of the ASEAN community are determined to move forward. The increased cooperation in education evidenced by all of the combined actions detailed provides an important background for the next chapter in the process of ASEAN higher education integration. The ASEAN community recognizes the need to create a common but not an identical or standardized ASEAN Higher Education Area (AHEA) that would facilitate the comparability of degrees and the mobility of students and faculty within Asia. While recognizing the fact that national and institutional variations in curriculum, instruction, programs, and degrees, resulting from historical, political, and socio-cultural influences, are bound to exist, it has managed to create a common ASEAN credit transfer system (ACTS), degree structure, credit, and quality control structures.

In conclusion, familiarization with the idea and concept of harmonization, as opposed to standardization, of higher education system in Southeast Asia is indeed an initial but a critical step towards the implementation of a meaningful and effective harmonization of higher education system in the region. While managers of higher education institutions and academics are not ignorant of the idea of harmonization, they tend to talk of it with reference to the Bologna process in Europe and the creation of the EHEA. Other stakeholders (particularly students) however are not very familiar as to how this concept could be realized in the context of Southeast Asia, which is culturally and politically diverse. Generally, students failed to appreciate the positive aspects of harmonization to their careers, job prospects and, of equal importance, cross-fertilization of cultures.

The task of creating a common higher education space is insurmountable in view of the vast differences in the structure and performance of the various higher education systems and institutions in Southeast Asia. Admittedly, we need to harmonize the internal structure of the higher education systems in the first instance before attempting a region-wide initiative. More importantly, the determination to realize this idea of harmonizing higher education in Southeast Asia should permeate and be readily accepted by the regional community. Typical of Southeast Asia, directives should come from the political masters. Thus, the role of Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) is very critical to a successful implementation of this idea of harmonization of the higher education systems. Although other regional bodies such as AUN and UMAP play important roles, at the end of the day, it is the nations and the individual HEIs who are the deciding actors who will determine the progress of the idea of harmonization in the region. Equally important, national prejudices and suspicions need to be put aside if we are to realize regional aspirations and goals.

Morshidi Sirat, Norzaini Azman & Aishah Abu Bakar

References

Abbas, M (2011).Globalization and its impact on education and culture. World Journal of Islamic History and Civilization, 1 (1): 59-69, 2011

Armstrong, L. (2009). The Bologna Process: A significant step in the modularization of higher education. World Education News & Reviews, 22(3). Retrieved on 7Feb 2014 from http://www.wes.org/ewenr/09apr/feature.htm

ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) Programme: Operational Handbook. SEAMEO RIHED, June 2012.

ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework for Education and Training Governance: Capacity Building for National Qualifications Frameworks (AANZ-0007), Consultation Paper. Retrieved on 7 February 2014 from http://ceap.org.ph/upload/download/20138/27223044914_1.pdf

Clark, N. (2007). The impact of the Bologna Process beyond Europe, part I. World Education News & Reviews, 20(4). Retrieved on 7 Feb 2014 from http://www.wes.org/ewenr/07apr/feature.htm

Enders, J. (2004). Higher education, internationalisation, and the nation-state: Recent developments and challenges to governance theory. Higher Education, 47(3), 361-382.

Hawkins, J. (2012). Regionalization and harmonization of higher education in Asia: Easier said than done. Asian Education and Development Studies Vol. 1/1, 96-108.

Hettne, B. (2005). Beyond the new regionalism. New Political Economy, 10(4), 543- 571.

Kehm, B.M. (2010). Quality in European higher education: The influence of the Bologna Process. Change, 42(3), 40-46.

National Higher Education Policies towards ASEAN Community 2015. Paper presented at the 5th Director General, Secretary General, Commission of Higher Education Meeting of SEAMEO RIHED in Nha Trang, Vietnam. Retrieved February 8, 2014 from http://www.slideshare.net/gatothp2010/7-national-highereducation-policies-towards-asean-community-by-2015-v2

Nguyen, A.T. (2009). “The role of regional organizations in East Asian regional cooperation and integration in the field of higher education”, in Kuroda, K. (Ed.), Asian Regional Integration Review, Vol. I, Waseda University, Tokyo, pp. 69-82.

Terada, T. (2003). “Constructing an ‘East Asian’ concept and growing regional identity: from EAEC to ASEANþ3”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 16/ 2, 251-77.

Wesley,M. (2003). The Regional Organizations of the Asia-Pacific: Exploring Institutional Change, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY.

Wallace, H. (2000). Europeanization and globalisation: Complementary or contradictory trends? New Political Economy. 5(3), 369-382.

Yan Liang. (2008). Asian countries urged to improve education quality. China View, Retrieved Febuary 8, 2014 from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-06/17/content_8388460.htm

Yepes, C.P. (2006), “World regionalization of higher education: policy proposals for international organizations”, Higher Education Policy, Vol. 19/2, 111-28.