You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

To what degree is academic freedom being geographically unsettled – deterritorialized, more accurately – in the context of the globalization of higher education? This was one of the issues I was asked about a few days ago when I spoke to a class of New York-based Columbia University students about the globalization of higher education, with a brief case study about Singapore’s global higher education hub development agenda. Some of the students were intrigued by this debate erupting (again) about Yale’s involvement in Yale-NUS College:

- 'Whose Yale College,' Inside Higher Ed, 28 March 2012

- 'Yale values to be tested in Singapore,' Yale Daily News, 29 March 2012

- ‘Academic freedom in New Haven and S'pore,' The Straits Times, 30 March 2012

Given that we only had a limited time to discuss these issues, I’ve outlined elements of the comments I would have added if I had a little more time during the Q&A session. And clearly, there is even much more to say about these issues than what is outlined below, but I’ve got grading to attend to, so this entry will have to suffice. And if any of you (the students) have more questions, please email me anytime. I’m obviously making this follow-up public on a weblog as well, as it fits into the broad themes covered in GlobalHigherEd.

The first point I wanted to reinforce is it is important to recognize that Singapore’s attempt to become the ‘Boston of the East’ is underlain by structural change in Singapore’s economy, and a related perception that a ‘new breed’ of Singaporean is needed.* Implementation of the global education hub development agenda is therefore dependent upon the exercise of statecraft and the utilization of state largesse. For example, nothing would be happening in Singapore regarding the presence of foreign universities were it not for shifts in how the state engages with foreign actors, including universities like Yale and Chicago. The opening up of territory to commercial presence (to use GATS parlance) as well as ‘deep partnerships,’ and the myriad ideological/regulatory/policy shifts needed to draw in foreign universities, has been evident since 1998. In an overall sense, this development agenda is designed to help reshape society and economy, while discursively branding (it is hoped) Singapore as one of the ‘hotspots’ in the archipelago which fuels, and profits from, the global knowledge economy.

Second, and as I noted on Thursday in my lecture, one of the three key post-1998 realignments is an enhanced acceptance of academic freedom in Singapore (in comparison to the 1980s and early 1990s). This is a point that was made in a 2005 chapter* I co-authored with Nigel Thrift and the same conditions exist today as far as I am concerned (though I do not speak for Nigel Thrift here).

Basically, local universities have acquired considerably more autonomy regarding governance matters; faculty now have historically unprecedented space to shape curricula and research agendas; and students have greater freedom to express themselves, even taking on ruling politicians in campus fora from time to time. I personally believe that the practice of academic freedom is alive and well in Singapore for the most part, and that critics of (for example) the Yale-NUS venture would be fools to assume this is a Southeast Asian Soviet-era Czechoslovakia: Singapore is far more sophisticated, advanced, and complex than this. Universities like the National University of Singapore and Singapore Management University are full of discussion, politically tinged banter, illuminating discussions in classes, and vigorous debates mixed with laughter over lunches at the many campus canteens. There is no difference between the debates I had about politics in Singapore when I worked there for four years (1997-2001) to those I have had at the ‘Berkeley of the Midwest’ (UW-Madison) from 2001 on, or my alma maters in Canada (University of British Columbia) and England (University of Bristol).

This said, Singapore is a highly charged ‘soft authoritarian’ political milieu: if certain conditions come together regarding the focus and activities of a faculty member (or indeed anyone else in Singapore, be they expatriates, permanent residents, or long-term citizens), a strong state guided by political elites has much room to maneuver – legally, administratively, procedurally, symbolically - in comparison to most other developed countries. In this kind of context, a focused form of ‘calibrated coercion’ can be exercised, if so desired, and a scholar’s life can be made very difficult despite the general practice of academic freedom on an average day- to-day basis. There are discussions about ‘OB markers’ (out-of-bounds markers) regarding certain topics, some forms of self-censorship regarding work on select themes, and perhaps a lift of the eye when CVs come in with Amnesty International volunteer experience listed on them. And at a broader scale, the Public Order Act regulates ‘cause-related’ cause-related activities that “will be regulated by permit regardless of the number of persons involved or the format they are conducted in.” Even before the 2009 tightening of revisions to the Public Order Act, I recall stumbling upon a ruckus (desperately searching for a post-lunch coffee, circa 1999-2000) when I witnessed police removing the leader of the opposition from the grounds of the National University of Singapore, after he attempted give a speech to students below the main library.

In short, Singapore is a complicated place, and one needs to work hard to understand the complexities and nuances that exist. Blind naïveté (often facilitated by temptingly high salaries) is as bad as cynical critique: like all places (Singapore and the US included), there are many shades of grey in our actually existing world. On this point it worth quoting the ever insightful Cherian George:

Singapore is not for everyone. Compared with countries at a similar income level, it is backward in the inclusiveness it offers to people with disabilities. It is a relatively safe country for families – but an innocent person who is wrongly suspected of a crime has more reason to fear in Singapore than in countries that treat more seriously the rights of the accused. And those who care enough for their society to stand up and criticise it have to be prepared to be treated as an opponent by an all-powerful government, enduring harassment and threats to their livelihoods. Being a writer immersed in Singapore has not blinded me to the system’s faults. But, one common form of critique in which I find myself unable to indulge is caricature, reducing Singapore to a society ruled by a monolithic elite, served by a uniformly pliant media, and populated by lobotomised automatons. Such essentialised accounts of government, media and people may satisfy the unengaged, but they generate too much cognitive dissonance for me. The Singapore I know – like any human society – is diverse and complex...

In short, the practice of academic freedom in Singapore is alive and well on a number of levels, but there are always significant political sinkholes that might open up; you just never know...

Academic freedoms & the Singapore Eye

But what are the many foreign universities that have stretched their institutional fabrics out across space into this Southeast Asian city-state doing about academic freedom in Singapore? In particular, if there is a lack of clarity about the nature of academic freedom given that guidelines are not codified, rules are unclear, and there appear to be no formalized procedures for dealing with serious contests, do foreign universities just accept the same conditions local academics work with?

The answer is a clear and resolute “no,” at least for highly respected universities like Chicago, Cornell, Duke, and Yale. Rather, what they do about academic freedom depends upon the outcome of negotiations between each of these foreign universities and the Singaporean state (sometimes in conjunction with local partner universities).

One of the more intriguing things about the development process is that most of the foreign universities that have engaged with the Singaporean state have developed what are effectively bilateral understandings of academic freedom. As I noted in 2005:**

Yet despite the influx of a significant number of American and European universities in response to the emergence of these new socio-economic development objectives, the concept of academic freedom, one of the underlying foundations of world class university governance systems, has received remarkably limited discussion and debate. The discussions and negotiations about the nature of academic freedom vis a vis Singapore's global schoolhouse have been engaged with in a circumscribed and opaque manner. Deliberations have primarily taken the form of closed negotiation sessions between senior administrators representing foreign universities, and officials and politicians representing the Singaporean state. The agreements that have been made are verbal for the most part, though they have also been selectively inscribed in the confidential Memorandum of Understandings (MOUs) and Agreements that have been signed between the Government of Singapore or local universities and the foreign universities in question. Strands of the concept have been brought over by the foreign universities, reworked during negotiations, and constituted in verbal and sometimes confidential textual form. The development of a series of case-by-case conceptualizations of academic freedom is hybridizing in effect. Through verbal agreements of unique forms, and through MOUs and Agreements of unique forms, foreign universities and the Singaporean state have splintered academic freedom in unique ways, unsettling previous notions of academic freedom in quite significant and hitherto unexamined ways.

See, for example, pages 6-8 of a Yale-issued summary of the agreement it reached with the Singaporean state.

Leaving aside the content of this message from Yale’s president, it is important to stand back and reflect on what is going on. In my opinion what we’re seeing is the creation of a strategically delineated understanding of academic freedom; one specified by just two parties in this case, and one that applies is a narrowly circumscribed geographic context (the Yale-NUS campus).

But think about the patterns here. Who is at the center of this aspect of the development process? It is the Singaporean state, including senior politicians such as the minister of education, the deputy prime minister, the prime minister, and in the Yale case senior leadership at NUS.

.jpg) Much like the London Eye, a myriad of universities work with the Singaporean state on this issue at a bilateral (case by case) level. Given this, no one knows more about how academic freedom can be negotiated and framed than the people at the center of the negotiation dynamic. A Singapore Eye of sorts (if this admittedly awkward analogy makes sense!) regarding academic freedom exists. A less obtuse analogy might be a hub (the state) and spoke (multiple foreign universities) one. And the outcome is a plethora of differentially shaped academic freedoms in Singapore, scattered across the city-state in association with the foreign universities, shorn as far as I can tell from much of the context local universities (and their academics) are embedded in. What a jumble of contexts, rules, and ways of operating!

Much like the London Eye, a myriad of universities work with the Singaporean state on this issue at a bilateral (case by case) level. Given this, no one knows more about how academic freedom can be negotiated and framed than the people at the center of the negotiation dynamic. A Singapore Eye of sorts (if this admittedly awkward analogy makes sense!) regarding academic freedom exists. A less obtuse analogy might be a hub (the state) and spoke (multiple foreign universities) one. And the outcome is a plethora of differentially shaped academic freedoms in Singapore, scattered across the city-state in association with the foreign universities, shorn as far as I can tell from much of the context local universities (and their academics) are embedded in. What a jumble of contexts, rules, and ways of operating!

In the global higher ed context, this pattern is not unique to Singapore. The same case could be made regarding Qatar, Abu-Dhabi, Dubai, and China (albeit to a lesser degree). What is noteworthy is that the current experts regarding the globalization of academic freedom are monarchs and political elites associated with ruling regimes, not the people associated with the higher education sector, for they are too focused on their own institutional agendas.

Another interesting aspect of this development process is the absence of any form of collective representation regarding academic freedom in these hubs. Universities (e.g., Yale, Cornell, MIT, NYU, Texas A&M) active in global higher education hubs informally share information, to be sure, but their capacity to share information, and model practices, depends on proactive and savvy administrators who know what to think about, what to ask about, and where the ‘non-negotiable’ line should be drawn.

Once they forge their agreement with the state in these hubs, they move on to the implementation phase. And then 1-3-5 years later in comes a new university, and this pattern starts afresh (and a new spoke is added). But the lines connecting the foreign universities are thin. For example, it is worth considering how many of the recent negotiations about academic freedom in Singapore have been informed by a critical analysis of the pros and cons of the University of Warwick’s deliberations about opening up a branch campus in Singapore circa 2005, including Dr. Thio Li-ann's substantial report about academic freedom in Singapore.

In conclusion: on absence vs presence

Well, I’ve gone on now longer than I expected. But I want to close off by asking you (the Columbia U students I am ultimately writing this for) to think about absence as much as presence. I’ve often encouraged my own students to think about this aspect of development, for while we can recognize focus on presence, absence matters just as much. Absence is itself a phenomenon associated with the development process: absence is often desired, or absence can exist as an outcome of the lack of capability, planning, and resources.

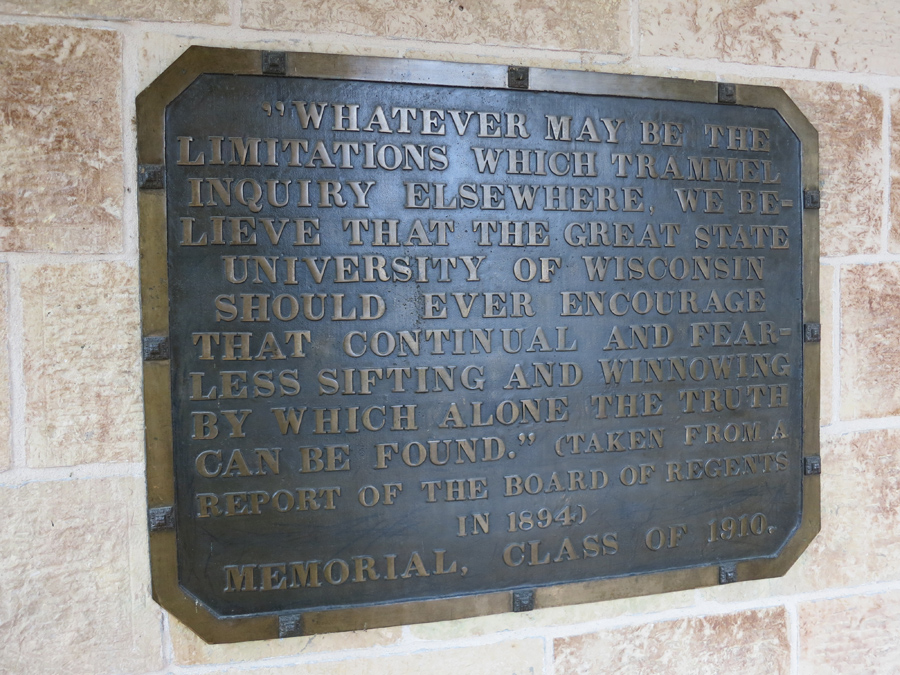

One thing that appears to be absent in Singapore as a whole are codified rules and guidelines about academic freedom: what it is defined as, what its limitations are, the balance of rights and responsibilities, and what its value is to higher education institutions. Interestingly you find all sorts of statements about the presence of academic freedom in Singapore, much like the ones I made above in all sincerity, or the ones put forward yesterday by Simon Chesterman (see ‘Academic freedom in New Haven and S'pore,' The Straits Times, 30 March 2012). [Professor Chesterman is Dean of the NUS Law School. Given that he is a law professor, and also son-in-law of the architect of Singapore’s global schoolhouse development strategy (Dr. Tony Tan Keng Yam, Singapore’s current President), his views are worth taking note of.] But statements and op-eds are just that; they are not the only things that create formally demarcated and secure spaces for researchers and students. What arguably helps realize and ground academic freedom are legible guidelines, codified procedures in cases of contest, laws, and symbolic affirmations of value such as this plaque I past by this morning after dropping my son off, cello on his back.

Mere media statements, even by important officials and member of the elite do not beget confidence about the real world importance of academic freedom, hence the desire of universities like Yale and Cornell to act – to codify - on a bilateral basis.

Mere media statements, even by important officials and member of the elite do not beget confidence about the real world importance of academic freedom, hence the desire of universities like Yale and Cornell to act – to codify - on a bilateral basis.

One of the more curious aspects of this ongoing debate about academic freedom is that Singapore has a reputation as a place that respects the rule of law, and it has a formidable reputation for the quality and clarity of regulation regarding key industries (e.g., finance). Yet the guidelines and regulations associated with the space to produce and circulate information and knowledge via universities situated in Singaporean territory remains limited, in my opinion. Why, especially when academic freedom keeps emerging as a concern of global actors like Yale (circa 2011-2012), Warwick (circa 2005), etc.? And why when a knowledge economy and society is just that -- one dependent upon the sometimes unruly production of valuable forms of knowledge?

Is bilateralism regarding academic freedom really the most effective approach? I’m not so sure for what it appears to do is provide fuel for debates, such as the one unfolding in Yale right now. Absence on this core issue (academic freedom) in Singapore as a whole, is arguably providing fuel for fire. Thus while some Yalies (is that what they are called?) seem to be disseminating remarkable unsophisticated understandings of how academia and politics works in Singapore, I would argue that the Singaporean authorities have created an opaque regulatory and discursive context regarding academic freedom vis a vis the production and circulation of knowledge. And as anyone who works on economic development knows, uncertainty is a problematic factor that can inhibit or skew the development process, partly because of misinterpretations.

A second absence is a global scale mechanism to ensure that the core principles associated with academic freedom are protected and realized as best it can be for the global community of scholars of which we are all (in Singapore, in New Haven, in Qatar, in Madison) a part. The long history of academic freedom is intertwined with the emergence of enlightenment(s), modernity(ies), and the associated development of societies and economies. Academic freedom helps create the space for the search for truth, the unfettered production and circulation of knowledge, and socio-economic innovation. But academic freedom has to be practiced, protected, codified, and realized, including while it is being globalized. The bilateralism evident in places like Singapore is inadequate in that the ‘foreign’ universities engaged in it are only thinking of themselves and not the global ecumene and community of universities. It is surely time for them to exercise some global leadership on such a core/foundational principle; one that has helped these universities become what they are.

Great to meet you all last Thursday. Be sure to think hard about this issue, gather diverse perspectives as any good student should, and feel 100% free to disagree with me. And hope next week’s discussions go well!

Kris Olds

* Olds, K., and Thrift, N. (2005) ‘Cultures on the brink: reengineering the soul of capitalism – on a global scale’, in A. Ong and S. Collier (eds.) Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics and Ethics as Anthropological Problems, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 270-290.

** Olds, K. (2005) ‘Articulating agendas and traveling principles in the layering of new strands of academic freedom in contemporary Singapore’, in B. Czarniawska and G. Sevón (eds.) Where Translation is a Vehicle, Imitation its Motor, and Fashion Sits at the Wheel: How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in the Global Economy, Malmö : Liber AB , pp. 167-189.