You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

If there’s one good reason to have a giant national conference for writers, it’s the chance to see once-a-year-in-person friends like Tom Williams, author of The Mimic's Own Voice and Chair of English at Morehead State University. We always make plans, then we get bookfair blindness like everybody else and the plans don’t happen. But without fail, year after year, we run into each other on the sidewalk or in a hotel lobby and take up the conversation as if uninterrupted. Tom has had a couple of big happy events this year, including the release of his blues novel, Don’t Start Me Talkin’, which arrived at my house only the day I left for the conference in Seattle. I know him well enough as a warm and generous person that I thought I'd best get an objective, third-party review. I asked Sean Singer, who I welcome to the blog for the first time, to take a look. --Churm

***

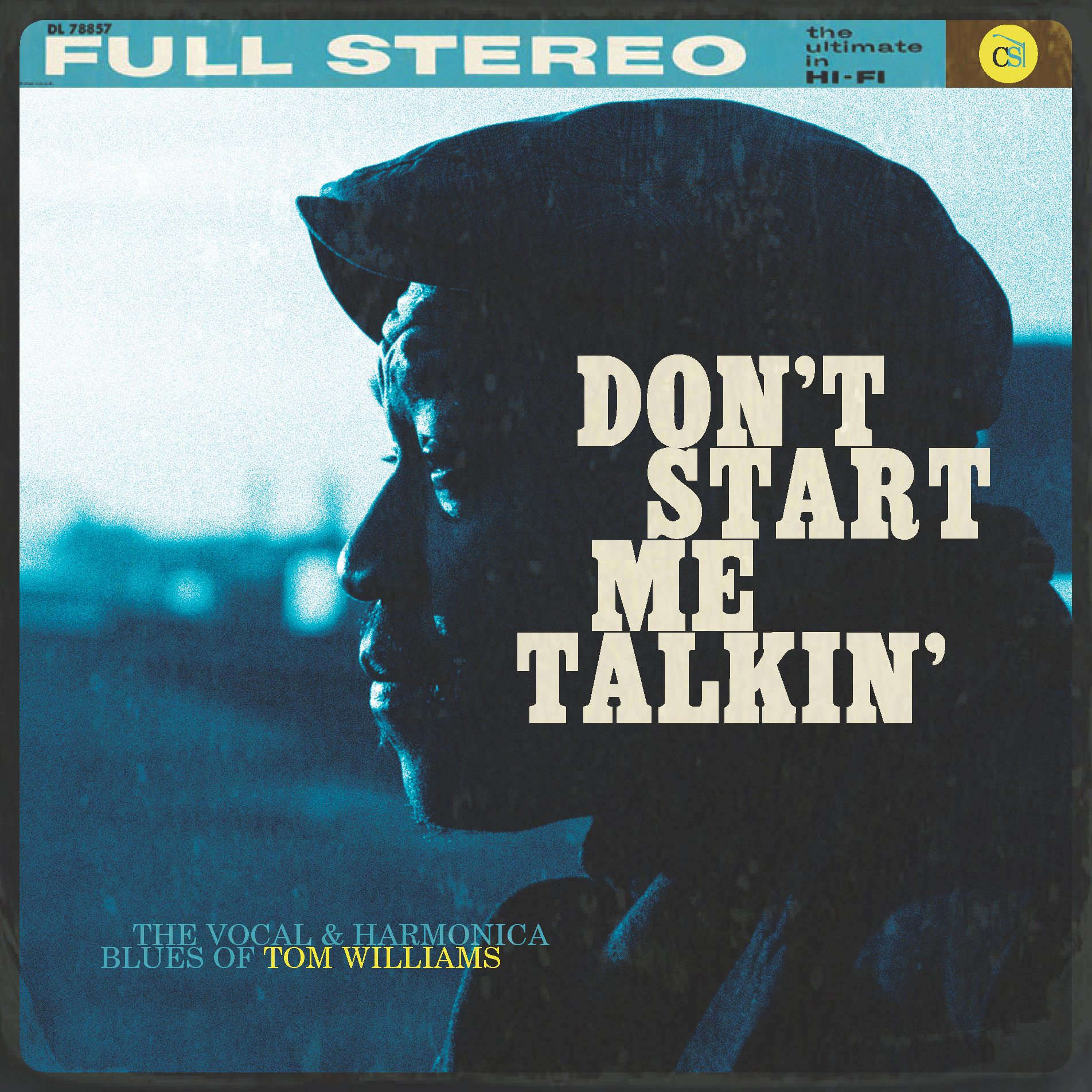

Don’t Start Me Talkin’. Tom Williams. Curbside Splendor Publishing, 2014. $15.95.

Review by Sean Singer

Tom Williams’s Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is a wonderful, subtle, and fascinating comic road novel set in and around the blues—as an aesthetic, a form, a lifestyle, a culture, and a myth.

Tom Williams’s Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is a wonderful, subtle, and fascinating comic road novel set in and around the blues—as an aesthetic, a form, a lifestyle, a culture, and a myth.

The term blues itself can be traced to Elizabethan English, and is a feeling, but also a musical form. The first published blues was by W.C. Handy, the “St. Louis Blues,” a three-line verse with A-A-B rhyme and a three-phrase pattern: I-IV-I-I7 / IV-IV-I-I / V7-V7-I-. With its background in the horrors of slavery and Reconstruction, the blues began with roots in gospel, field hollers, prison work songs, minstrelsy, folk songs, and African griots. The blues is so integral a part of American music and culture, often in an invisible way; though it began as a source of strength and limitless creativity in the face of brutal repression, it filtered through rock, country, and rap into everything we hear.

Don’t Start Me Talkin’ follows Brother Ben (“the other B.B.”), the last remaining Delta Blues musician, and his accompanist and man-at-hand, Sam Stamps, who is the narrator of the novel. Partly playing father and son, mentor and student, and Vladimir and Estragon, Ben and Sam travel the blues circuit to perform. That’s the surface. Beyond the plot, Ben and Sam deliver the blues not only through their songs—frequently renditions of Sonny Boy Williamson II (aka Rice Miller)—but through performances of characters, themselves blues musicians. Not unlike Rafi Zabor’s The Bear Comes Home, which follows an alto saxophonist who is a brown bear, and his musical accompanist, Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is both an exploration and a parody of some things culture holds dear about blues music.

Ben changes his way of speaking, his clothes, his drink, his car, his fanciful tales, to create subterfuge. He channels “blues-iness” through these affectations, never letting the real source or person from behind the façade: “Wardrobe next. And though the kind of swap meet rags we want are available in every neighborhood with an African American population above ten percent, Ben always depends on the stores along Crenshaw to provide the tackiest and ugliest. Today’s expedition to the two-for-a-dollar bin yields an armful of shirts quite popular circa 1975. Ben singles me out for a long-sleeved, iridescent number: ‘Looks like the color of motor oil,’ he says, laughing his everyday laugh, not the stylized one he employs on stage.”

In this example, of many in the novel, Williams cleverly shows Ben finding what Robin D.G. Kelly calls, in Race Rebels, a “hidden transcript.” The transcript means an infrapolitical or covert agenda of resistance and self-expression in the lives of ordinary African American men (Sam refers to this throughout the book), something at odds with prescriptions of the African American middle class. Ben is like a moving theater, a public stage on which Ben as an African American struggles to achieve a measure of autonomy and dignity. As Ben overturns part of the master-narrative of the Blues, he also creates a comic tableaux.

A scene where this is occurs is when Ben and Sam are stopped by a cop for a moving violation; Ben convinces the cop that he and Sam are father and son looking around for a condominium:

So far, Officer Reese hasn’t written anything, and his posture softens as Ben catalogues the expensive condo fees from Pensacola to Tallahassee and other points along I-10 that he, a simple Mississippi shipyard worker, encountered. He keeps swaddling himself in this stereotype until the infraction’s nearly forgotten. And now he completes it: "And after I spent so much my pension on this here Cadillac, I can’t be payin’ no 800 hundred dollar a month." He then leans on the cough. His wheezing delivery gets Officer Reese’s attention even further. Finally, he clears his throat and chuckles. "I wants to leave somethin’ behind for my boy here, but oncet I saw this here car I said, ‘Give me one nice car to ride in before some hearse take me to the boneyard.’”

Ben subverts himself via the blues constantly, as a matter of course. The serious question one must ask is: Is the blues itself a performance? What makes it authentic? Can we identify Robert Johnson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Lead Belly, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Memphis Minnie, or any blues figure as real?

Thinking about an encounter with a hip hop posse, Sam considers rap’s performances of itself vis-à-vis the blues:

I don't say anything, but I have concerns. Whether you call it rap or hip hop, I know it's huge and has even crossed over the way blues did way back when. Yet I'm no willing listener. Some rap has real power and energy, and, yes, authenticity. No MC alive is as creative as Sonny Boy, but with that opinion I'm—as usual—in the minority. Still, for all its potency, rap's like a bulldozer. It only works in one direction: plowing right over you. Rare is the number that lightens your spirit. If it does, then people keepin' it real, as if "real" can only be can only be defined by money, bitches, and guns. I'll never join the ranks of those like my mother who want rap's voices monitored or silenced. Lord knows they'd want to shut Ben and me down next, what with our celebrations of drinking and womanizing and picking up firearms with ill intent. But rap isn't for me. Blues got there first. Reached inside and never let go.

In the sense that Ben performs himself as he performs the blues, Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is a postmodern and meta- book. It comments on itself as you read along. Constantly funny, engaging, and risk-taking, the book gives pleasure on every page. Physically, and also structurally, the book is arranged like a blues record, by Brother Ben, also called Don’t Start Me Talkin'. The chapters are blues song titles: “Fattening Frogs For Snakes,” “Keep It To Yourself,” “One Way Out,” etc.

Angela Davis has discussed the consciousness-raising groups of the 1960s which rendered explicit the underlying politics shaping women’s lives: “…it is possible to detect ways in which the sharing of personal relationships in blues culture prefigured consciousness-raising and its insights about the social construction of individual experience.” There are almost no women in Don’t Start Me Talkin’, and this is my only minor quibble with a serious and seriously funny novel. A woman’s perspective would have added a crucial frisson and insight that Ben and Sam are unable to offer.

Don’t Start Me Talkin’ is an important and beautifully crafted novel that describes and evokes the complicated relationships between race and art, identity and culture, and the changed landscape of America and how our culture has made truth and beauty commodities. Ben says, “I don’t care ‘bout no goddam past. This is today and today Brother Ben says no tapes.”

***

Sean Singer’s first book, Discography, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, selected by W.S. Merwin, and the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. His second book, Honey & Smoke, is forthcoming from Eyewear Publishing in 2015. His work has recently appeared in Pleiades, Iowa Review, New England Review, and Salmagundi. He has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Rutgers-Newark and is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. He lives in New York City.