You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

I welcome back poet Sean Singer, whose previous review at the blog was here. --Churm

***

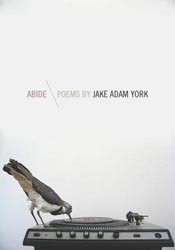

Abide. Jake Adam York. Southern Illinois University Press, 2014. $15.95.

Review by Sean Singer

Jake Adam York’s fourth book, the posthumously published Abide, will continue to raise his profile as one of our finest elegists, and strongest lyric poets of his generation. In his four books York fused his own biography as a son of a small town in Alabama with his own elegies, portraits, and re-imaginings of martyrs of the long Civil Rights Movement.

Jake Adam York’s fourth book, the posthumously published Abide, will continue to raise his profile as one of our finest elegists, and strongest lyric poets of his generation. In his four books York fused his own biography as a son of a small town in Alabama with his own elegies, portraits, and re-imaginings of martyrs of the long Civil Rights Movement.

York was a friend of mine, and his death was terrible for poetry, and for me personally. Reading his work in the past tense rather than in the subjunctive has its eerie, yet hopeful lights. Eerie because his sudden death from a stroke at age 40 shocked all who knew him; hopeful because he showed how to maintain affection for the universe, and for the ugly, tormented history of the American experiment, even as he set a critical gaze upon America’s attachment to white supremacy.

In Abide, York favored tiered tercets, and when he used other stanza forms, the middle or second lines are frequently indented, suggesting a kind of pause of thoughtfulness; more than a caesura, the indented spaces mean that there has always been a “wait” in the Civil Rights Movement, and that this “wait,” though it often meant “never” now may mean “work in progress.”

Abide’s title is taken from “Abide With Me,” as played by the Thelonious Monk Septet on Monk’s Music in 1957; their version was taken from the 19th century hymn “Eventide” by one William H. Monk. The opening line in “Abide with Me” alludes to Luke 24:29, “Abide with us: for it is toward evening, and the day is far spent.” York’s elegiac tone has this sentiment; the poems look back, and move forward with feeling. They especially use epistolary form, and the seemingly endless variations of letters York was able to imagine are a powerful way to convey his peaceful message.

Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” from 1963 defends the strategy of nonviolence, sometimes called passive resistance to racism. King advises four steps to this resistance: Collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”

York’s book uses the idea of using a letter for resistance to engage in many conversations: with Cy Twombly, Yusef Komunyakaa, Woody Guthrie, the breath, a hundred dollar bill, a record sleeve, another person, and himself, among others.

Monk himself makes more than one appearance; in “Epistrophy,” York uses the phonograph’s stylus as a way to have Monk’s music bridge the gap between York as a child and his Dad:

Monk has to stay

in his child-red wagon,

while the stars spin through the pines.

Now, I turn the music back,

turn it over, as light eases

back into the sky. Dad

wakes the blanket, the amp,

the smell of solder, smell

of oil instead of iron, twilight

instead of twilight. Then

the room is young again,

the smoke, the silence, the stars

years away, until dusk

raises its hands from the keys.

Then the needle gasps,

and I stand. I reach,

his hand on mine,

and breathe again.

The poem is a master lesson on how to effectively use enjambment to convey tension and meaning. The poem uses repetition, not unlike the song “Epistrophy”, to use doubleness: son-father, listener-musician, live performance-recording, white-black, young-old; the distances of time between the child and parent are those between them and the music. For example, “back”; “twilight”; and “smell.” Monk becomes “dusk” who raises its hands and the needle is given agency and “gasps.” Subtle and always moving across space like an element of time, York’s poem is as fine as any he’d written.

York’s enjambments do a lot of work to slow pacing, and to wind whatever images he’s using into the speaker and away from him. For example:

It reaches back, like the future,

which is just another kind

of history, a shape

for whatever’s missing

that fills its own outline. (“Letter Written on a Record Sleeve”)

or

Maybe we keep saying

their silences between our words,

the shape of their voices

in ours, in ours

the warmth that haunts

their absent lungs. (“Feedback Loop”)

or

You are not here,

you are not here

in Birmingham,

where they keep your name,

not in Elmwood’s famous plots

or the monuments

of bronze or steel or the strew

of change in the fountain

where the fire hoses sprayed. (“Letter Already Broadcast into Space”)

History, especially civil rights history, for York, was almost like a residue on a sieve, on which the moisture is the history that the poems document. York used his artistic process to give mythology to his own life, and the life of that history, the roots of which were his same town, Gadsden, and state, Alabama. His poems have both a “vertical” shift in modes (his personal life and tastes); and a “horizontal” shift in chronology (he moves from before his birth, to his childhood, to his own mind looking back).

By not taking race for granted, and by engaging the processes by which memories hold sway on history, York treated his subjects with bravery and honesty. In “Inscription for Air,” for example, York uses a narrow, river-like form that uses commas to control the flow of information, even as his ideas are enlarged by their quick pacing; the poem is one long sentence, but many lines stretched along a path.

Traditionally the functions of elegy were three: to lament, to praise, and to console. It did these by expressing grief, by idealizing the dead, and by finding solace in meditation. York’s poems do all these, but the elegy form was essentially for York a political one. The political processes of the Civil Rights Era are often memorialized within the confines of myth (for example, that of Rosa Parks) in an attempt to scrub narratives free of conflict, Marxist sentiment, or complexity; since this is the case, repetition tends to encode such myths for easy consumption. Repetition and observing codes are what York’s poems tend to needle and massage: like Milton he uses elegy for denunciation of political corruption.

York did not favor pyrotechnics or experimentation: his work grows out of the lyric tradition, not unlike Charles Wright’s. In my favorite poem, “Letter Written in the Dark”, he takes the scribbled abstractions on ancient Rome, those of the painter Cy Twombly, to find his own methodology for creating:

Shinbone, Dirtseller, Sleeping Giants—

dream phrases, names

memory’s mad illegible,

the notes I find are written over one another,

tangled as the hair a pillow offers afternoon.

Shenandoah, Three Sisters, Tobacco Row—

this is what the blind hand writes in the dark.

Moving through Twombly’s fiery use of language in his paintings, to small town slurs, to his own argument with lyric. Here, York was open to the experience of being “there to write it down.” “Letter Written in the Dark” is a beautiful masterpiece.

For York, a tall, bald, white man, to elegize martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement, perhaps those terrorized by people who looked exactly like him, took not just courage, but reflection.

In this way, his poems pose an ethical question, through ethical thinking: How to disturb those histories with elegies? York believed that memory was a living monster, one with which each line we utter and each action is made in the breath. His poems reframe our understanding of our relationship to our haunted pasts. May Abide make readers understand the powerful ethical force of York’s poems.

***

Sean Singer’s first book, Discography, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, selected by W.S. Merwin, and the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. His second book, Honey & Smoke, is forthcoming from Eyewear Publishing in 2015. His work has recently appeared in Pleiades, Iowa Review, New England Review, and Salmagundi. He has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Rutgers-Newark and is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. He lives in New York City.