You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Over the past decade Bring Data! has emerged as a new cri de coeur across American colleges and universities.

Campus planning initiatives, policy discussions about student success (retention, advising, institutional outcomes, and value added), instructional interventions and innovations, operational effectiveness, and efforts to enhance the return on investment (ROI) are all data dependent. And because “Big Data” has emerged as a powerful engine of analysis and insight in the consumer and corporate sectors, it is no surprise that institutional leaders (along with patrons on campus boards and in state legislatures) have great expectations for the role of Big Data and Analytics across all sectors of American higher education.

We can trace the origins of this movement, in part, to Margaret Spellings, currently president of the University of North Carolina System. As Secretary of Education under George W. Bush from 2005-2009, Secretary Spellings frequently cited the “Deming Dictum” – In God we trust; all others bring data – as a charming if disarming way to articulate the both the K-12 and higher education policy priorities of the Bush Administration. And in her current position as the leader of the University of North Carolina System of Higher Education, President Spellings has also served notice about her “bring data” priorities for planning, policy, and decision-making across for the 17-campus UNC system.

Yet great expectations (and great needs) notwithstanding, bringing Big Data and Analytics into the operational DNA of American higher education, might be appropriately characterized as a Sisyphean task. Why?

First, presidential and provost proclamations supporting data-informed campus decision-making notwithstanding, much of the decision-making in higher education is too often “informed” by opinion and epiphany, not data and evidence. Recent national surveys of presidents, provosts, CFOs, and CIOs reveal that the many (and in some surveys the majority) do not believe that their institutions do a good job of using data to inform campus planning and decision-making.

Second, to paraphrase a long ago New Yorker cartoon, higher education has lots of information technology, but too many colleges and universities seem to have little timely and useful data and information to aid and inform campus planning and decision-making.

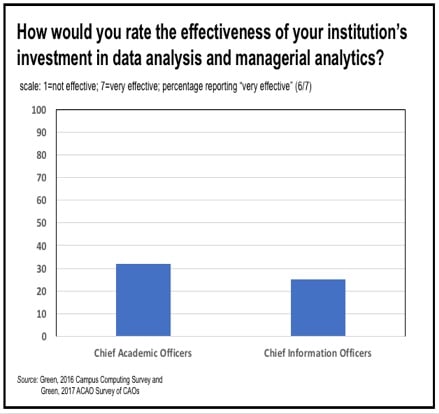

Third, both CIOs and CAOs seem to agree that, in general, their institutional investments in data and analytics have not been “very effective.” The data about the effectiveness of institutional investments come from the fall 2017 ACAO Survey of CAOs and the 2016 Campus Computing Survey.

Fourth, the “data culture” at too many institutions continues to use as a data weapon (what you did wrong; how your unit failed) and not as a resource (how do we use data to do better).

Finally, the core task of data integration and transparency remain a major challenge. Big data analytics depend on a rich “gumbo” of data from a wide array of campus sources, often generated by several different technology platforms and data bases. As a technology rather than a campus culture issue, data integration and transparency – creating the “data gumbo” – should, in theory, be the easiest of these factors to resolve in a timely matter. In fact, it may be among the most difficult.

The different, and often disparately structured and defined data from Student Information Systems (SIS), campus financial systems, student financial aid systems, HR/personnel files, ePortfolios, Learning Management Systems (LMS), alumni/development programs, and other databases large and small that are scattered across campuses (and servers and now also the Cloud) are the core resources that inform and fuel program assessments, institutional interventions, and outcomes analysis. The business intelligence and data mining tools that, a more decade ago, allowed Wal-Mart to discover a surprising run on beer in its Florida stores ahead of Hurricane Frances in 2004 are the same tools that colleges and universities now want deploy to gain information and insight about how to improve student success efforts, and how to assess the impact of campus programs and the efficiency of campus operations.

These same data resources and tools are essential for campus efforts to respond to the mandates – some new and some ignored for years but now enforced – from accrediting associations, government regulators, and various higher ed sponsors that increasing demand hard data and real evidence to document claims for program effectiveness and institutional outcomes.

Framing the Data Babel Problem

Over the past four decades higher education’s technology providers have repeatedly promised data integration and transparency.

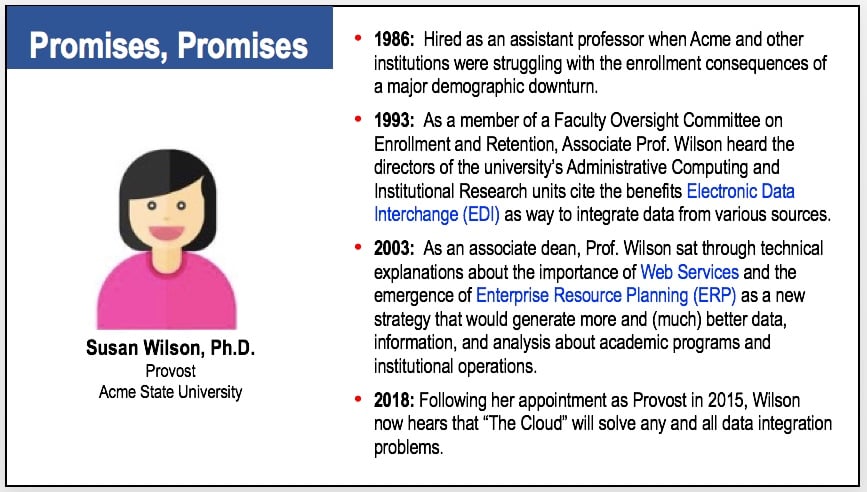

Consider the hypothetical case of Susan Wilson, the provost at Acme State University, a mid-sized public comprehensive institution of some 14,000 students. Susan Wilson began her academic career as a newly-hired assistant professor at Acme State in 1985, as campuses across the US were grappling with strategies to address enrollment problems created by the demographic downturn caused by the declining size of the high school graduating cohort in her state and across the US.

- In 1993, as a member of a Faculty Oversight Committee on Enrollment and Retention, Assistant Professor Wilson heard the directors of university’s Administrative Computing and Institutional Research units cite the benefits Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) as way to integrate data from various campus sources which would facilitate analytic efforts to enhance lagging recruitment and retention activities.

- A decade later, as an Associate Professor and Associate Dean, Prof. Wilson sat through technical explanations about the importance of Web Services and the emergence of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) as a new strategy that would generate more and (much) better data, information, and analysis about academic programs and institutional operations for her and her Acme State colleagues.

- And following her appointment as Provost in 2015, Susan Wilson now feels she has been captive to way too many presentations about data and analytics from both campus personnel and technology providers. These presentations, including those from “analytic specialists” with barely five years of experience in the higher education market, typically extoll the potential of Big Data and Cloud Services to generate insight and analysis to address a range of critical campus issues, including timely student interventions to reduce DWIF numbers, as well as informing efforts to increase retention and degree completion, and supporting a wide range of student success initiatives. ''

Despite the recurring promises during her rise through the ranks over her decades at Acme State, Provost Wilson does not believe that any of these “new technologies” have truly delivered on oft-offered (and much needed) data transparency, data integration, and now, Big Data Analytics. Admittedly, she knows that the Student Success movement may have added more elements to the data gumbo; however, she also knows that the underlying challenges of integrating the key data elements remain significant. Consequently, Susan Wilson, like many of her CAO colleagues, remains understandably skeptical that future investments in analytics will provide the much-needed data, information, and insight for Acme State.

Data Transparency and Integration

Data transparency and integration issues might be characterized, in part, as a “cross-platform integration challenge.”Critical data come from a variety of sources and technology applications or platforms and then have to be coded or processed in a way that allows links to individual student records ahead of analysis.

This involves more than simply linking student data via a common ID number in several data files.Data structures, common data definitions, and other issues typically pose significant challenges that requiretime and money (and often outside expertise) to resolve linking and data integration problems.

The analytical potential for the data linkage and “data gumbo” is a gestalt where the “sum” (information and insight) from the analytical work should be more than the “parts” were the work is limited to just one or two sets of data from different sources (e.g., background and transcript data from a Student Information System and transactional data from a Learning Management System).

Unfortunately, rather having access to a “data gumbo” rich with integrated data sources, most colleges and universities continue to experience “data babel” – critical operational challenges that involve applications, platforms, and data bases (often six to eight or more on some campuses) that do not “talk” with one another and that are difficult to aggregate, integrate, analyze, and exploit.

Admittedly, cross platform issues (challenges) are common to higher education.And yet some cross-platform strategies and solutions do work. For example, the emergence of the ) standards for learning management systems reflects efforts to provide common standards across various LMS applications. The relatively fast and widespread adaption of the LTI standard among higher ed’s LMS providers provides a model for how tech providers might collaborate on standards that would facilitate data integration and cross-platform data migration.

From Watching to Doing

Some institutions have solved the “data babel” problem. Arizona State and Georgia State, among others, have each earned accolades and have become the envy of many of peers for their work with data and analytics in service to student learning and student success. Georgia State University reports its impressive gains in retention and graduation are fueled, in part by analytic work that monitors some 800 student risk factors, and also by a significant investment in support services. But ASU and Georgia State are analytic outliers in the landscape of American colleges and universities.

So rather than continuing to talk about what Arizona State and Georgia State have done with Big Data, the key question pressing most institutions is how can they do what Arizona State and Georgia State have done – faster, easier, and at lower cost?

One component of the solution involves identifying the operational and structural barriers that impede efforts to integrate data across the key applications and platforms. Addressing the structural barriers will require that the various platform providers – ok, the harsher term is vendors – learn to play nice with one another and their campus clients when it comes to data access and integration.Simply “sending data streams to the Cloud “ – the strategy I’ve heard in several presentations in recent years, will not solves the data compatibility and integration challenge of presented by data streams from multiple platforms.

A second key component involves strategies to optimize the use of student data in digital learning, leveraging the data stream from adaptive courseware and other resources to improve prospects for course completion before course correction is no longer possible. Efforts to leverage digital learning resources and strategies must include operational strategies that exploit data, provide information and insight, and launch interventions faster and better to improve the likelihood that more students succeed.

A third component of the solution must focus on faculty.Data-laden PowerPoint presentations and research papers typically lack the compelling narrative required to engage faculty – to help explain to faculty how analytic insights and the interventions that emerge from Big Data analytics can help their students.Compelling evidence of impact, coupled with a change of the too-common campus culture of using data as a weapon to using data as a resource are essential if campus officials hope to build faculty trust and foster faculty engagement in student success initiatives.

Ultimately, it’s time for institutional leadership, and technology providers to stop talking about the benefits of Big Data and start working on ways to resolve the data babel and related issues that impede institutional efforts to exploit data to enhance our understanding of student learning, to help target interventions intended to increase retention and degree completion, and inform decision-making about campus management and administration.

Acknowledgement: My thanks to Karen Vignare, director of the Personalized Learning Consortium at the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, and James Ptaszynski, Vice President for Digital Learning at the University of North Carolina System Office, for their very thoughtful comments on an early draft of this blog post.