You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

malerapaso/istock/getty images plus

I’ve never been much of a fan of puzzles. To be honest, even when I was a kid, puzzles just frustrated me, and I had no interest. I would plug away because my mother thought it might exercise some part of my brain that I didn’t normally use. But to me, the entire enterprise of solving puzzles seemed pretty pointless.

This year, I happened upon an article about bucket lists that included “Completing a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle.” I’ve generally thought that bucket lists are a bit maudlin, but the article captured my interest enough that I downloaded it and deleted all the things on the list that I knew I’d never want to do or that might be physically dangerous—skydiving, sailing around the world and so forth. I also added some things notably missed (like having a grandchild or retiring), and I landed on a list of around 150 items that represented a pretty good set of things to shoot for.

Completing a 1,000-piece puzzle was on the list. Since it hadn’t qualified as life-threatening and wasn’t truly distasteful, I thought I should probably give it a try. Of course, 1,000 pieces did sound overwhelming, but why not? The worst that could happen, so I thought, was abject failure—perhaps so much frustration that I’d set it aside and regret never finishing it. What I didn’t expect was that I would learn a set of lessons that would significantly inform my leadership as an academic dean. Those lessons are as follows.

Make your brain work differently. Yep, moms are always right: doing the puzzle made me see things differently and clearly worked a part of my brain that had not been engaged for a while. As I watched the image take shape, I recognized that making my brain work differently, seeing things in different ways and expanding my brain muscle really did have positive effects at work as well. As I would discuss an issue with my leadership team, hear a complaint from a student or consider a request from a supervisor, I started to think differently. I also started to listen and to hear differently, and I stepped back and took a different perspective. Like turning a puzzle piece around to see how it might fit, I could see myself searching for new ways to fit solutions to problems.

Make your brain work differently. Yep, moms are always right: doing the puzzle made me see things differently and clearly worked a part of my brain that had not been engaged for a while. As I watched the image take shape, I recognized that making my brain work differently, seeing things in different ways and expanding my brain muscle really did have positive effects at work as well. As I would discuss an issue with my leadership team, hear a complaint from a student or consider a request from a supervisor, I started to think differently. I also started to listen and to hear differently, and I stepped back and took a different perspective. Like turning a puzzle piece around to see how it might fit, I could see myself searching for new ways to fit solutions to problems.

Sort. As I worked on that very large puzzle, I found that I had to categorize the pieces. There were, after all, 1,000 of them. It would have been impossible, at least for me, to have a pile of all those pieces with no organization at all.

So I sorted them by image, color and shape, which enabled me to work on sections of the image rather than trying to tackle it all at once. Similarly, leaders sort constantly. We compartmentalize our work and ask ourselves questions like “Is this a strategy task or a maintenance task? Am I working on my writing and scholarship or is this about my supervision? Is this management or leadership? Is this problem an issue of resources, logistics or vision?”

A good leader is not only constantly sorting but also connecting: “This new program could be a great published case study.” Sorting is an essential task and, as with puzzles, when coupled with connecting the parts, the whole image comes into focus.

Create a process that works for you. You can’t just magically put a puzzle together. Rather, you need an approach or a process, and different people choose different ones. For me, I wanted to start from the bottom of the puzzle and work my way up. Other people build from top down while others think from outside in. Few would approach from inside out—those outside pieces are easier to spot—but I suppose some might prefer that way.

In short, there isn’t one right approach. Just because a certain process seems smarter or more efficient for you doesn’t make it right for others. And while that doesn’t really matter in the world of puzzles, when we start thinking about leadership, it does. Consultants, coaches or book authors may promote a single path to ideal leadership—that there’s only one right way to lead. But, ultimately, you need to select your own distinct process that’s comfortable and works best for you.

Attack the task in waves. I found that I needed to work pieces of the puzzle in phases. I wouldn’t have wanted to just sit down and devote all my attention to it, uninterrupted for hours and hours. Being able to look at the task as something to return to rather than something to complete in one sitting is helpful when thinking about leadership practice—it, too, must be something you return to over and over again. Sometimes you’ll devote a good deal of specific attention to it, such as when you attend a professional development training. But then you can also set it aside and come back to it at different intervals. You will refine it; you’ll add a piece here and there.

Shift your strategy. Working a puzzle requires shifting strategies throughout the process. Sometimes I would look for a color match; other times I would look to see if I could find a shape match. Sometimes I had to look at the overall picture; sometimes I would search for a small detail on a piece. At moments the only way to make progress was to painstakingly try every possible piece that might fit.

What I realized as I worked was that taking one approach all the time was a losing strategy. Working a puzzle, like learning to lead, requires attempting various approaches: trying, failing, trying again, seeing what works and learning from that. At times, it will feel like you are painstakingly checking every piece to see what will fit for the context, the people, the time, the available resources. Shifting perspectives is an absolute necessity when refining leadership capabilities.

Take a step back. At times I got stuck when doing the puzzle. I would try all my strategies—color, fit, pattern—but nothing would work. So then I would step away. I would walk around the room, take a break, get a snack, check my email … and my eye would be drawn back to the puzzle table. I’d look at the picture of what the puzzle would eventually become, I’d look at the pieces all spread out on the table where I was working and I’d realize exactly where a piece I spied belonged. And the work would begin again.

It was from stepping away from the detailed pieces that I was able to re-engage. Similarly, as leaders, we sometimes need to lay all the pieces of a problem out in front of us and then take a break. And when we come back, we’ll suddenly see that piece that we’ve been missing—the one that obviously fit all along. Sometimes that means we need to stop obsessing about the problem, to keep it from keeping us up at night. While it may feel like we’re slacking off—“Hey, I’m taking a break”—it is a part of seeing the bigger picture as a leader. Taking a step back can be really difficult, but it is an essential strategy.

Sometimes pieces fit, but they’re wrong. This was a complete and utter surprise to me. I was at least halfway through the puzzle before realizing that sometimes pieces fit perfectly, but when I looked at the image more closely, I realized they weren’t the right pieces in the right places. And trying to fit the next piece was sometimes my only real confirmation that I had misplaced a puzzle piece.

In leadership, sometimes we think we have the right solution: everything looks good—you put a strategy in place, try it out and it seems like it’s going well. But then it suddenly seems to fall apart, so it is necessary to back up, undo the work you’ve done and start over.

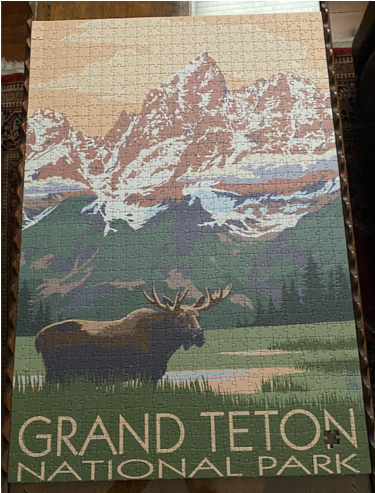

If you’re missing a piece, you may just have to move on. I must confess that my 1,000-piece puzzle had one piece officially missing. After I completed the 999 pieces, I had a gap, like a missing front tooth. I searched for it under sofa cushions, in the trash, in the box, in the instructions—absolutely everywhere. But that piece was simply gone.

If you’re missing a piece, you may just have to move on. I must confess that my 1,000-piece puzzle had one piece officially missing. After I completed the 999 pieces, I had a gap, like a missing front tooth. I searched for it under sofa cushions, in the trash, in the box, in the instructions—absolutely everywhere. But that piece was simply gone.

I looked up online what to do when a puzzle is missing a piece and found suggestions to write to the source of the puzzle asking to have the specific piece cut and sent. I tried, but the company said that was not something they were able to do. They were willing to send me a new puzzle of the same type or another if I preferred. But, in the end, I just decided to deem the 999-piece puzzle complete and rolled it up and stored it away. I moved on.

Sometimes as an academic leader, you’ll also find that something just won’t work or works imperfectly. Certainly, you’ll work with some people who just won’t like you or your leadership style. You’ll grapple with problems that, no matter how hard you try, will not be solvable. Ruminating on those problems—focusing on the one missing piece instead of the 999 perfectly fitted pieces—is self-defeating. Sometimes you may have to move on. The key is to feel good about the larger accomplishment, not that one missing piece.

In the end, my experience with puzzles was short-lived, but the leadership lessons I learned will stick with me. With this 999-piece puzzle completed, I feel I’m done with this item on my bucket list. I learned a lot from the experience and encourage my colleagues to give it a go. It is through engaging these sorts of mind-stretching experiences that we grow to be our best leaders.