You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Ivcandy/digitalvision vectors/getty images

Anything I read on any topic in the past few months starts with the impact of COVID-19 and the changes brought about by the pandemic. Some of those changes turned out to be positive; others remain challenging. The transformations we’re seeing made me reflect more on changes in higher education and which ones we can build on -- particularly in the ways we support graduate students’ and postdocs’ professional development and career preparation. In this commentary I share recommendations for how colleges and universities should respond to the needs of current graduate students and postdocs and provide professional development, focusing particularly on oral and written communication support.

We already knew change was needed and that we could not continue preparing graduate students and postdocs primarily for faculty positions. Sir Ken Robinson has been pointing out the need to reform public education for a very long time, noting that we can’t keep on doing what we did in the past. It took a pandemic to see some major shifting in education; most of us swiftly switched from in-person to online mode. The momentum is there, and we should use it to make the changes we’ve been delaying on the -- now disproven -- grounds that changes in education happen very slowly.

I began my research before the pandemic started, reviewing websites of 20 graduate schools in the Northeast United States and Canada and interviewing 13 graduate school deans as well as 21 graduate students from one large, major public research university. What I learned suggests a new model for providing professional development in general, and oral and written communication support in particular. By communication skills, I mean graduate students’ and postdocs’ ability to articulate their research and its value to different audiences using appropriate genres and styles in writing and oral communication. I recommend a systematic approach that would help diversify students’ career options by offering key resources to help graduate students and postdocs learn to communicate to different stakeholders the value and application of their work/research.

How to do this? First, by offering the support consistently, and second, by providing the support through continuing courses -- not only one-off programs.

Current Communication Support Models

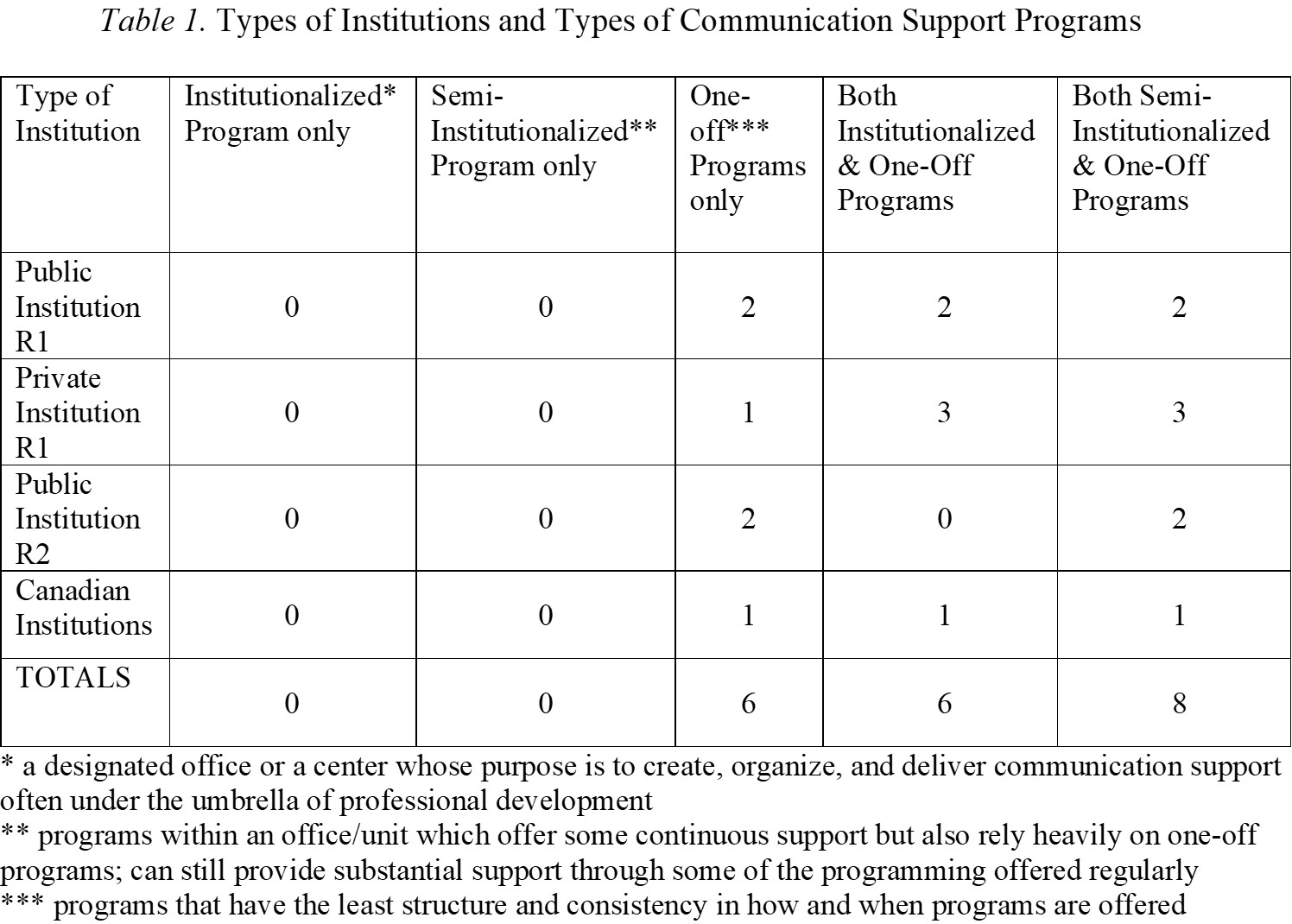

Professional development offices, graduate schools, departments and students themselves all actively invest in efforts to provide programming that meets different student needs. Nevertheless, some changes in approach and perception could yield important progress. Table 1 shows three distinct and two hybrid models of how communication support is organized. The data come from my 2018 pilot study of 20 institutions in the Northeastern United States and Canada.

The change in approach concerns how programs are organized: specifically, coordination and investment at the institutional level characterizes the most effective programs, providing better access, visibility and sustainability. At a more local level, the doctoral students I interviewed want more discipline-specific, curated support within their departments in the form of courses -- contrary to the widespread assumption that the graduate curriculum has no room for more courses. These two observations reveal both macro- and micro-level arguments in favor of institutionalization.

The change in approach concerns how programs are organized: specifically, coordination and investment at the institutional level characterizes the most effective programs, providing better access, visibility and sustainability. At a more local level, the doctoral students I interviewed want more discipline-specific, curated support within their departments in the form of courses -- contrary to the widespread assumption that the graduate curriculum has no room for more courses. These two observations reveal both macro- and micro-level arguments in favor of institutionalization.

Macro-level change. At the macro level, an office focused exclusively on professional development broadly, and communication support more specifically, should offer existing one-off and semi-institutionalized programs continuously and consistently. That approach allows for the development of a clear mission, vision and tangible goals. Having dedicated staff whose role is to consistently provide support and build relationships with other constituencies ensures better accessibility, visibility and sustainability in the form of institutional knowledge. Providing support at the institutional level ensures access for all students, and even more important, it cultivates transferable skill building by creating space for students to develop those skills alongside peers from different disciplines.

Micro-level change. Support on the micro level includes programming developed collaboratively by institutionwide and disciplinary programs (and/or courses). Collaboration with disciplinary faculty could increase faculty investment in promoting such programs. The Council of Graduate Schools’ and the Association of American Universities’ reports on Ph.D. career development emphasize the need to change the culture and perception of Ph.D. career pathways. Both organizations emphasize the need to change the common belief that getting a Ph.D. leads to the professoriate and to make efforts toward career diversification. Collaboration with faculty members about what kind of support is offered to doctoral students and postdocs and in what form is likely to lead to a more supportive attitude from advisers. Furthermore, providing micro-level support within departments ensures that the soft skills needed in diverse careers are developed alongside academic work. Finally, pairing broad-level support with more field-specific support creates space for a holistic approach to doctoral education and training.

A New Model

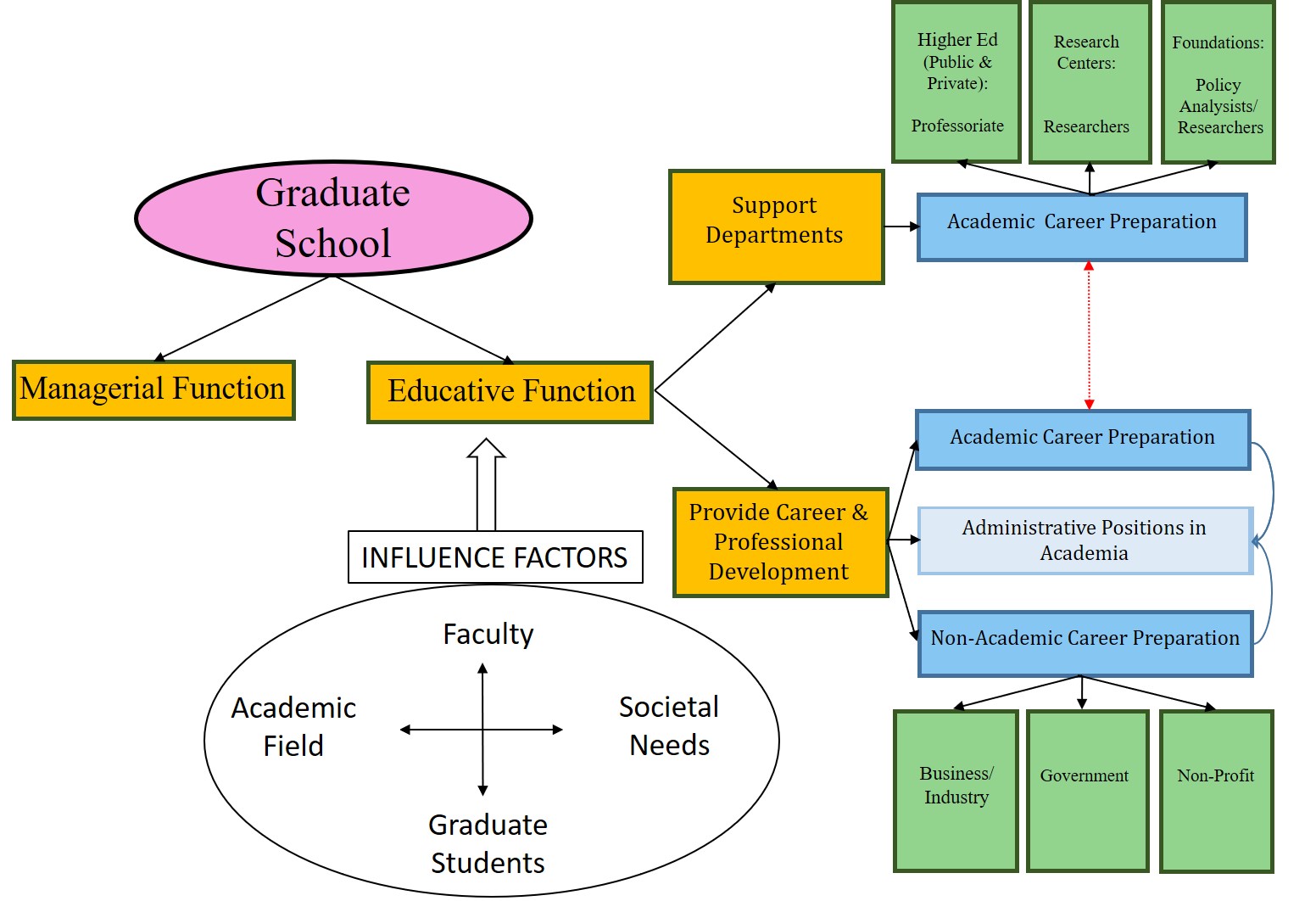

Based on what I've learned from deans, faculty members and students, as well as my own experience as both a consumer and a presenter of support programs, I have developed a new model for integrating professional development into graduate education. This model captures the influence and functions that create a pathway for expanded career pathways through establishment of institutionwide professional development programs for grad students and postdocs.

The diagram on the right illustrates a proposed model for organizing professional and career development programs, as well as integrating them into graduate education. The macro level is the educative function of graduate school, while the micro level is the career preparation and communication support provided through departments and graduate school collaboration. These two levels should complement each other, not compete.

The diagram on the right illustrates a proposed model for organizing professional and career development programs, as well as integrating them into graduate education. The macro level is the educative function of graduate school, while the micro level is the career preparation and communication support provided through departments and graduate school collaboration. These two levels should complement each other, not compete.

The red dotted arrow on the right between academic career preparation through departments and though graduate schools indicates that the two inform each other. The graduate school can provide more general support for academic careers, such as development of transferable skills (the macro level), whereas departments can provide more specific and field-related support (micro level).

Professionals who hold administrative positions in graduate schools, and who understand both the needs of graduate students and the culture of departments, can best implement my proposals. Many such positions are currently filled by people familiar with the departments they come from, who must figure out graduate school (administrative position) along the way.

Administrative positions in academe, represented in the diagram in lighter blue and informed by both academic and nonacademic career preparation, reflect the current trend of employing Ph.D. graduates to work on professional development programs. This is an emerging area of career opportunities for doctoral students who could benefit from learning about administrative work while staying informed about academic career preparation. Humanities students, in particular, could explore how their skills can be applied in positions in university innovation centers, offices for career and professional development, and student advising.

This model conceptualizes the changes that are necessary to build an expanded pathway for graduate students. Graduate students and postdocs should explore this career option early in their graduate studies/postdoctoral work and prepare for such hybrid administrative/academic positions.

Key Questions

Moving to a new model along the lines that I’m recommending will require institutions and graduate programs to consider and answer some important questions, including:

What is the role of faculty in providing professional development and communication support? Making necessary changes will require additional research on how to engage faculty members and ensure that they receive enough support for providing professional development and communication support at the department level. A vital step is to learn more about faculty views of these programs. As already discussed, a lot of support already exists among faculty, but the resources are often underutilized. Students might participate more if faculty members, especially advisers, encouraged them to do so. Better understanding faculty perspectives may lead to more constructive solutions and approaches to meeting graduate students’ need for professional development and communication support.

How does communication support relate to time to degree and completion rates? Could providing the right kind of professional development consistently and systematically help students complete their degrees? One study found that one-off writing boot camps don’t have a long-term effect on student productivity and outcomes. However, it might be different if support was offered continuously through courses -- the format preferred by the doctoral students I interviewed.

Moreover, student participants’ own reports about writing retreats indicate that these programs have more value than just encouraging writing productivity. They offer benefits beyond the obvious and intended ones, including community building and mental health support, to cite just two examples. Given the importance of mental health in graduate education, the possible correlation between communication support programs and Ph.D. completion deserves further consideration.

How does communication support relate to retention? The most common reasons for leaving graduate school are family-related demands (30 percent), military or job conflict (17 percent), and dissatisfaction with the program (16 percent). And the groups that are most likely to leave graduate school are women and minority students. Because change in family status affects women and minorities more than others, investigating whether oral and written communication support could help these groups persevere is crucial.

In my own experience of providing communication support virtually in the last year and a half, I’ve seen the increase in participation of parents of young children, commuters and underrepresented groups (e.g., LGBTQ+) who report that participating in programs such as a weekly writing accountability group has helped them make progress. One participant reflected, “I started going to writing sessions and retreats to give me something to anchor my weeks and provide structure. They did that, but I was totally unprepared for the support and accountability I also found during these sessions; they became an essential part of my weeks, and without them, I would not have finished my dissertation as successfully as I did.”

Nationally, doctoral student attrition rates are at about 50 percent; answering the questions I’ve raised might help us get more students across the finish line. In my current administrative postdoc position, I'm focused on seeking answers to such questions. Administrators should support, and doctoral students and postdocs should pursue, such research in order to inform national standards and best practices for providing professional development and communication support to diversify graduate students’ and postdocs’ career options.

The pandemic forced us to adapt quickly, but it also showed us that we can do it. Now that we know change is possible and can even be rapid, it’s high time we responded to the changing times and career milieus by providing the support students want and need. Creating designated roles and institutionalizing graduate students’ and postdocs’ professional development and communication support is vital for providing this much-needed programming consistently and systematically.