You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A Sample Student Journal

Used with permission of Quinn Lewis

In fall 2018, we -- Zachary Nowak, an instructor, and Reed Knappe, a teaching assistant -- experimented with several new pedagogical techniques we had encountered in educational literature but never tried. They included polling on cell phones, frequent low-stakes quizzing and a lecture-light class structure, all of which yielded positive results. The innovation that worked by far the most magic in our course, however, was having our students keep a course journal.

Dannelle Stevens and Joanne Cooper's Journal Keeping: How to Use Reflective Writing for Learning, Teaching, Professional Insight and Positive Change (Stylus, 2009) convinced us that journals were a powerful way to have students engage with the course materials and accomplish a number of learning outcomes. Stevens and Cooper make the case that a journal is "concrete evidence of one's evolving thought processes, documenting valuable, often fleeting glimpses of understanding." Course journals would be not just a repository of notes but also of in-class exercises; we would ask students to look back and annotate earlier entries to show them how they were progressing in the course.

The course in question was an introduction to American environmental history. Of course, we wanted students to acquire broad historical content about such themes as pollution, environmental justice, ecological imperialism, energy and wilderness concepts. Even more importantly, we wanted them to learn the basics of historical research and argument, and in the process complete a lengthy final project tailored to have enduring significance in their own lives and careers.

We introduced the idea of course journals on the first day of class, giving the students a handout in which we described how the journals were meant to be much more than just a notebook. At the same time that these journals functioned as places for writing class notes in the familiar mode, they were also intended to be a kind of sandbox for sketching out ideas they would read about and discuss in class, as well as for completing assignments and in-class reflections integral to the course design.

We suggested -- but did not require -- that they get a sketchbook with thick, unlined pages rather than the typical spiral-bound notebook. We also asked them to leave the first page blank and then to write out the course's learning outcomes on the second page and their own aspirations for the class on the third page. Thereafter, they were to leave a third of each right-hand page blank (more on this below). For students with accommodations for using computers, or those who had made a special request to use a computer, we allowed for completion of a digital course journal.

We asked the students to bring their course journals to every class meeting and every discussion section. At the early phases of the semester, we had them do things mainly corresponding to the lower levels of Bloom's taxonomy. For instance, in one of the very first classes, we asked them to write up their own definitions of "environmental history." On another day, we had them work in small groups to make lists in their journals of the citations from an article on the Columbian Exchange, differentiating between primary and secondary sources.

At the end of lectures, we often had them summarize or reflect upon what they thought were the most important points, in their journals. In discussion sections, students began work on their final projects early in the semester, and this, too, was channeled into their course journaling. We asked the students to log their progress on the final paper, noting when they had turned in their initial proposal, completed the review of sources, and written their first 500 words.

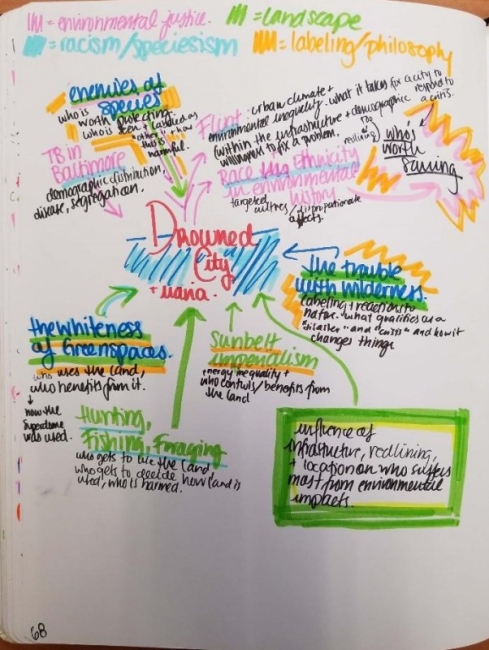

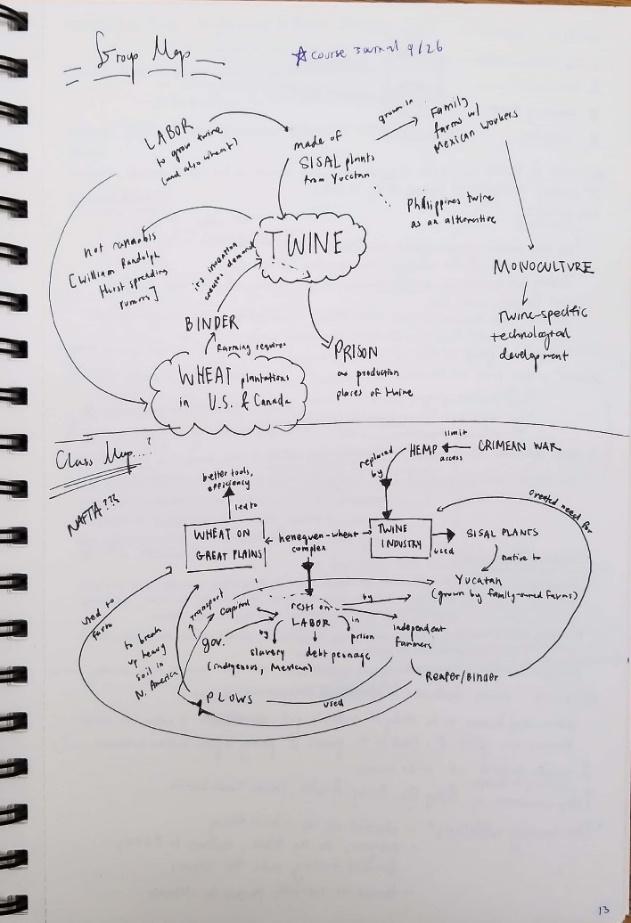

As the students learned the basics, we increasingly asked them to do higher-order tasks in their journals, often drawing on what they had learned in their own personal experiences. That started with going back to earlier entries and annotating in the third of each page we had asked them to leave blank. Our students returned in the sixth week to the definition of "environmental history" that they had written in the first week; they wrote a new definition that incorporated what they had learned in the meantime. After discussing William Cronon's essay "The Trouble With Wilderness," we had them apply the article's arguments to wildernesses or nature areas near their own hometowns. At other times, we asked them to visualize two or three articles by drawing concept maps in their journals, and then connect them conceptually. (Course journals are great places for students -- either individually or in groups -- to draw concept maps. They have to pull apart articles and then re-assemble them on one page. Please see example illustrated here, used with the student's permission.)

As the students learned the basics, we increasingly asked them to do higher-order tasks in their journals, often drawing on what they had learned in their own personal experiences. That started with going back to earlier entries and annotating in the third of each page we had asked them to leave blank. Our students returned in the sixth week to the definition of "environmental history" that they had written in the first week; they wrote a new definition that incorporated what they had learned in the meantime. After discussing William Cronon's essay "The Trouble With Wilderness," we had them apply the article's arguments to wildernesses or nature areas near their own hometowns. At other times, we asked them to visualize two or three articles by drawing concept maps in their journals, and then connect them conceptually. (Course journals are great places for students -- either individually or in groups -- to draw concept maps. They have to pull apart articles and then re-assemble them on one page. Please see example illustrated here, used with the student's permission.)

Each time we asked students to make an entry in their course journals, we recorded the date and the assignment on the course website. Students knew that the entries would be graded on a three-point scale. That prevented them from simply writing one-line responses, but also allowed them to treat the course journal as a sandbox rather than as a place where they had to write immaculate prose. Incidentally, this system also made grading relatively easy for the two of us.

In the end, we felt that the course journals had proven a superb way to build students' abilities, and our students seem overwhelmingly to have reached the same conclusion. More than 85 percent agreed that the journals were moderately to extremely useful. Their comments were more revealing. The journals, one student wrote, "opened up a space for me in my own thinking to reflect on what we were learning and discussing." Another student highlighted that the journals "made me more accountable for my own learning, not skipping the process by taking the time to complete every entry."

We had also wondered whether having a special journal would have any particular effect and were pleased to read that at least one student appreciated it: "I was skeptical about the course journal (I prefer binders), but we ended up liking it. Having a special place for your thoughts, and thick paper on which to write, made me take more care with my assignments."

As was to be expected, a minority of the students didn't appreciate the pedagogical subtleties. Several commented that they hadn't minded the journals but didn't think they had enhanced their learning. Another wrote "I enjoyed all of the experimental learning techniques but was not sold on the value of the journal. It sometimes felt like middle school and like we were mindlessly copying things down just because we had to." We think that comment says much more about the superior pedagogical training that some middle-school teachers have and many professors lack. It was also an expression, we believe, of occasional student resistance to active learning, which is probably inevitable when shaking things up with unfamiliar methods.

In the final analysis, in keeping with the argument put forth in Dannelle Stevens and Joanne Cooper's book, we found that course journals were an effective way to engage students across a wide range of learning processes. The journals proved an excellent way to have students reiterate what they'd learned, go back and process it further a few weeks later, and then make a comparison in the final weeks of the course. They showed us, the instructors, that the students had learned, but also rendered that process visible to them.

Course journals were a simple technology but sublimely adaptable: we saw how they could be equally useful in an introductory survey as in an upper-level seminar or in a physics lab as in a comparative literature course. They were easy to integrate into both lecture meetings and discussion sections, and we look forward to using them again this coming semester.