You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

More than half of white Americans (55 percent) believe there is discrimination against white people in the United States today. That finding -- from a survey by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Harvard University's T. H. Chan School of Public Health -- seemed to surprise many, at least to judge by the news media attention the survey received.

The survey also found that 11 percent of white Americans believe they have personally been discriminated against in applying to or while at college.

While the survey did not focus on affirmative action policies, much of the commentary about the findings has done so. Educators who back affirmative action may scoff at the 11 percent. And there is evidence that white people are not losing admissions slots due to affirmative action. Look at what happens when affirmative action is eliminated: in states that have banned the consideration of race in admissions -- such as California and Michigan -- white enrollment at highly competitive colleges did not go up after the bans were put in place. (Enrollment of Asian-Americans grew substantially, however, and that of African-Americans fell sharply.)

But numerous recent studies have found that many Americans -- in particular those who backed the election of Donald Trump as president -- believe that white people are facing discrimination. A Washington Post-ABC News poll during last year's election campaign asked which was a “bigger problem in this country -- blacks and Hispanics losing out because of preferences for whites, or whites losing out because of preferences for blacks and Hispanics?”

Nationally, more people (40 percent versus 28 percent) said that the answer was preferences for white people. But among Republicans who supported Trump for their party's presidential nomination, the overwhelming answer (54 percent to 12 percent) was that preferences for black and Latino people were hurting white people.

Such poll results (and the reactions to them) show very different perceptions depending on one's race and politics. There also appears to be a difference in press treatment of findings about perceptions of discrimination.

The NPR findings on white people's views received widespread attention. Findings of a survey of black people (by the same trio of groups that did the survey of white people) appeared to receive less attention. In that survey, 92 percent of African-Americans said they believe discrimination against black people exists in the United States today. And more than a third of African-Americans (36 percent) said that they had personally experienced discrimination while applying to or in college. As with white people who said the same thing, it is impossible to know the individual circumstances of each person. But for older African-Americans, who grew up in an era of legal segregation of many colleges and universities, that discrimination existed is a fact.

The Splits on Affirmative Action

Extrapolating poll results such as these to views of colleges' affirmative action programs is difficult -- in large part because affirmative action means different things to different people and some definitions appear to result in lower levels of support. Generally, support in general terms (when people appear to be thinking about recruitment efforts) is strong. But support drops if affirmative action is defined as "a preference" for some groups over others in how candidates for admission are evaluated.

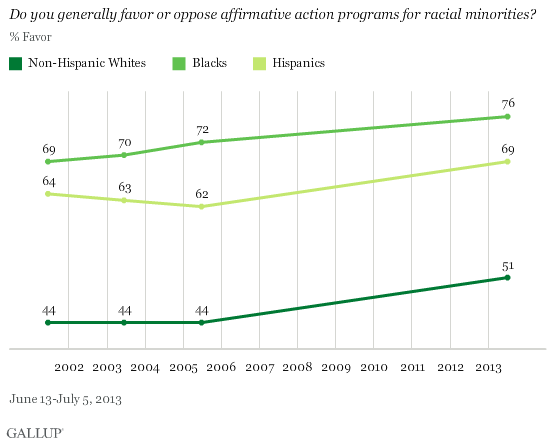

Consider these results from Gallup polls over a number of years, which show increasing (and majority) support for affirmative action (when not defined) but much lower levels of support when asked if colleges should consider someone's race in admissions decisions or focus only on merit.

Gallup Polls on Affirmative Action

![Which comes closer to your view about evaluating students for admission into a college or university -- [Rotated: applicants should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few minority students being admitted (or) an applicant’s racial and ethnic background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who otherwise would not be admitted]? Line graph shows percentage who answered “solely on merit” at 69 percent in 2004, 70 percent in 2007 and 67 percent in 2013, while “racial/ethnic background considered” was at 27 percent in 2004, 23 percent in 2007, and 28 percent in 2013. Source: Gallup, polling conducted from June 13 to July 5, 2013.](http://content.gallup.com/origin/gallupinc/GallupSpaces/Production/Cms/POLL/46_0c04yrueit-6htz0pda.png)

Is ‘Merit’ an Accurate Word for Describing the Rest of College Admissions?

Educators who support the consideration of race and ethnicity as one factor among many in admissions tend to be frustrated by questions that frame the policy choice as between "merit" and considering race and ethnicity.

Numerous parts of the admissions process -- the ability to pay for test-prep or paid application essay "help," not to mention the correlation between family wealth and the quality of high school one attends, or legacy preferences -- favor wealthier applicants, who typically are white or, in some cases, Asian.

A poll conducted by Gallup in 2016 (with questions provided by Inside Higher Ed) asked members of the public about the factors they thought should be considered in college admissions decisions. The top answers were high school grades and test scores -- generally the factors that people who advocate for "merit-based admissions" talk about. But the poll found greater support for such factors as athletic ability and alumni child status than it did for race or ethnicity.

There is also some evidence that support for factors other than grades or test scores may go up if people feel their children -- including their white children -- could benefit.

Consider the research of Frank L. Samson of the University of Miami. He found, in a survey of white California adults, they generally favor admissions policies that place a high priority on high school grade point averages and standardized test scores. But when these white people are focused on the success of Asian-American students, their views change.

The white adults in the survey were also divided into two groups. Half were simply asked to assign the importance they thought various criteria should have in the admissions system of the University of California. The other half received a different prompt, one that noted that Asian-Americans make up more than twice as many undergraduates proportionally in the UC system as they do in the population of the state.

When informed of that fact, the white adults favor a reduced role for grades and test scores in admissions -- apparently based on high achievement levels by Asian-American applicants. When asked about leadership as an admissions criterion, white ranking of the measure went up in importance when respondents were informed of the Asian success in University of California admissions. So in at least some cases, "merit" may be a bit flexible to some who advocate for it.