You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Kenyon College President S. Georgia Nugent knows her campus is picturesque – and it’s hard to argue otherwise. Ohio’s oldest private college sits atop a hill covered in greenery, its landscape framed with gothic architecture and split down the middle by a 10-foot-wide gravel path that spans the college and in the autumn is dotted with red and orange leaves fallen from the trees hanging overhead. (If that’s not serene enough, check out the college’s 380-acre nature preserve.)

“In the fall, it’s like you’re in God’s country,” Nugent, the college’s president, said during a recent visit to Inside Higher Ed.

Naturally, it’s the perfect campus for a film set at a college. Happily, Kenyon has alumni in Hollywood. And not coincidentally, one of them just chose the campus for the setting of his new film "Liberal Arts," which was warmly received last month with a rare standing ovation at its Sundance Film Festival premiere. "Liberal Arts" is directed, written by and starring Josh Radnor, of "How I Met Your Mother" (and, though few remember, "Not Another Teen Movie") fame.

“I think it’s likely to be huge for Kenyon,” Nugent said. She knows Radnor, though their paths didn’t cross at Kenyon – he graduated in 1996 and Nugent didn’t become president until 2003. “We live in such a social media-heavy world that just having a college’s name be better-known is such a huge benefit.”

Radnor plays Jesse Fisher, an unfulfilled, fumbling 35-year-old admissions counselor at a college in New York state, longing for his own college days. Jesse returns to Kenyon per the invitation of a favorite professor who is retiring, and is reawakened by the development of an invigorating – but complicated – relationship with 19-year-old Zibby, played by Elizabeth Olsen (yes, that’s the other Olsen sister). The two bond over their shared love of music and literature – all against the backdrop of Kenyon’s campus.

The college’s alumni also include Paul Newman and Allison Janney -- the latter plays a literature professor in "Liberal Arts." Janney said at Sundance that her performance was inspired by the Kenyon drama professor Harlene Marley, who taught both Janney and Radnor. “It’s the most beautiful love letter to Kenyon College,” she said of the film.

To hear the actors talk about it, Kenyon itself is a co-star. Just as writers often have actors in mind when forming scripts, Radnor thought of specific campus locations – the chapel, the coffeehouse – while writing the screenplay. The crew told Radnor it was the easiest location scout they’d ever done. While there, they stayed in campus housing. “It was kind of like bringing a film crew back to college for a month,” Radnor said. “But you were making a movie instead of going to class.”

It seems to have worked -- IFC Films reportedly paid seven figures to distribute the film later this year.

As it happens, Kenyon just last year approved the curriculum for its new film major, which so far has been a hit among its 1,600 students, particularly among male ones.

Based on Nugent’s knowledge and the buzz about the film so far – not to mention the fact that the film was made by and stars actual Kenyon alumni – it seems like "Liberal Arts" will stay true to the campus’s character, and may have staying power in the college film canon. It’s of course too soon to say what effect the film will have on Kenyon – so instead, we decided to take this opportunity to check in with other campuses where classic college films were set. Not all of them identified their respective institutions, and not all were on location for the entire movie. But all made a lasting impression on academics, students and the general public alike.

And now, a look at how five very different movies portrayed the campuses on which they were filmed and/or set, as observed by film scholars at each institution.

NATIONAL LAMPOON'S ANIMAL HOUSE (1978)

The film that shaped so many perceptions of Greek Life was shot at the University of Oregon, but set at the fictitious Faber College. As the building that stood in as the Delta House fraternity has since been torn down (though the spot is marked with a small plaque), the most recognizable locations in the film are the student union where the food fight takes place, and the administration build ing, whose president’s office doubled as Dean Wormer’s office.

ing, whose president’s office doubled as Dean Wormer’s office.

As the story goes, then-Oregon President William Beaty Boyd sorely regretted passing on an opportunity that would have set "The Graduate" at the Eugene campus (that film ended up at the University of California at Berkeley -- more on that below). Thankfully for the filmmakers, whose raunchy script made the movie a tough sell, Boyd jumped at his next opportunity to play host to a major motion picture.

“[The producers] said ‘Oh, don’t worry, it’s all very proper and it will shine a lovely light on Oregon.’ There would be no nudity and no drinking and drugs and that sort of thing. And then of course there was,” said Michael Aronson, associate director of cinema studies at Oregon. “Ultimately there was a fair amount of tension while it was made…. The university probably officially doesn’t love what it presents about college life, but unofficially, it’s been embraced by the university. It’s kind of a seminal college film.”

"Animal House" can be a selling point for the university, sometimes: tour guides talk about it with prospective students, and Aronson himself remembers the department chair pointing it out during his on-campus interview several years ago. Today, the film screens on campus at some point each year.

“I don’t think it’s anything the university tries to hide – while obviously condemning the behavior of the students,” Aronson said. (The fraternity in the movie, in fact, is said to be based on one at Dartmouth College, where the screenwriter Chris Miller pledged.) “Part of the pleasure of it is that it’s a kind of excessive fantasy of the crazy parts of college life. But…. it’s not Citizen Kane."

RUDY (1993)

The inspiring story of Rudy, a dyslexic student who overcomes economic, academic and personal obstacles to realize his dreams of playing for the Fighting Irish, memorialized Notre Dame football in film. But it tends to divide people on campus, said Jim Collins, chair of Notre Dame’s Department of Film, Television and Theatre.

While "Rudy" captures the immense pride Notre Dame takes in sports – which goes beyond your typical school spirit, Collins said, to the point where “sport becomes somehow transcendent” – it omits other things the university has to be proud of. People refer to the dilemma as the “Rudy factor,” he said.

“For some people, anyway, 'Rudy' as a film really represents everything that they take great pride in about Notre Dame. But there’s another enormous percentage of the Notre Dame community that thinks that’s all well and good, but that can also have a downside,” Collins said. He noted the university’s advertisements that run during football games, showing students and faculty doing humanitarian work around the globe. “It’s not just 'Rudy' and rah-rah. It’s also a deep commitment to social justice, a deep commitment to working in impoverished areas of the world.”

Collins views the ads to some degree as evidence that Notre Dame is concerned about a stereotype casting it as just another big football program. "Rudy" helped revive the perception of Notre Dame as a football powerhouse that was apparent throughout and after the 1920s and ‘40s, when coaches Knute Rockne and Frank Leahy were at the helm.

“There are a lot of Notre Dame alumni, and a lot of my current students, who will be quick to tell you they came to Notre Dame, but not because of the Rudy factor,” Collins said. “In many ways, 'Rudy' has always appealed more to the alumni than it has the current students.”

GOOD WILL HUNTING (1997)

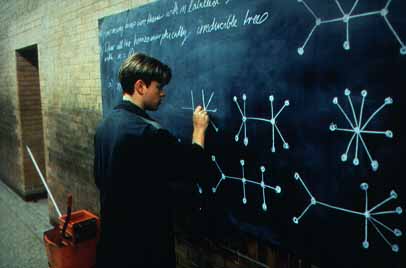

"Good Will Hunting" may have won the Best Original Screenplay Oscar, but to William Uricchio, director of the Comparative Media Studies program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it largely failed in its portrayal of MIT. (And not just because much of it was filmed at the University of Toronto.)

“What the thing got completely wrong – and what really irked me – was the portrayal of the intellectual atmosphere here,” Uricchio said. “All those notions of status and hierarchy -- that’s not important. It’s really more  an engagement with questions themselves on a really fundamental level.”

an engagement with questions themselves on a really fundamental level.”

The idea that anyone at MIT wouldn’t take a genius seriously because he was a janitor from Boston’s lower economic class is unrealistic and “almost offensive,” Uricchio said. “He fits right in with some of the kids here.”

In the film, one mathematics professor tries to reach out and tutor the young Will, but he lashes out and the professor has to turn to an old roommate, a therapist who teaches at Bunker Hill Community College. The two bond as Will falls in love with a young woman preparing to graduate from Harvard University and move on to Stanford University.

MIT students didn’t take too much of an issue, apparently – after the film won two Academy Awards, they “hacked” a campus building, blacking out windows on 16 floors to create the shape of an Oscar when the lights go on at night.

THE GRADUATE (1967)

Kenyon’s Nugent said she’s heard people refer to "Liberal Arts" as the next "Graduate," and while that’s clearly high praise, it’s not hard to draw similarities. The meandering Benjamin, recently back in California after graduating from an East Coast college, is focused on and motivated by nothing until he flees to Berkeley to reunite with Elaine, the daughter of Ben’s former lover Mrs. Robinson. Elaine is a student there, but the film was shot both at Berkeley and the University of Southern California.

"The Graduate" is probably more likely to trigger thoughts of its defining Simon and Garfunkel song than of Berkeley. But the concept of the university and the city that are embodied in "The Graduate" – ideas of freedom and possibility – were formative for many film scholars during their own college years, said Anne Nesbet, chair of Berkeley’s Film and Media Department.

Despite growing up nearby, Nesbet actually didn’t spend much time in Berkeley until after she graduated from Harvard (where screenings of the film took place all the time), long after the 1960s- and ‘70s- era depicted in the film.

“[Cambridge was] where I got my idea of what ‘Berkeley’ was all about. Of course, then I ended up at Berkeley for graduate school and discovered Berkeley wasn’t like that at all, not actually,” Nesbet said via e-mail. “The idea of Berkeley was a place where people were somehow particularly free and radical and interesting. Maybe that’s still true about Berkeley, but it’s in a much subtler way than in the ‘idea.' ”

Despite the film’s now-iconic status, Nesbet hasn’t in 20 years heard one Berkeley student mention it. “Like college students everywhere, the films they mention spontaneously are the ones they saw last week or hope to see next month,” she said. “ 'The Graduate' sort of falls through the cracks. Those cult films of a certain era don’t seem to show up in classes all that much.”