You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions delivered a speech in Las Vegas last week pushing a policy point that has been a staple of President Donald Trump’s recent rhetoric: sanctuary cities -- municipalities or localities that prohibit local law enforcement from enforcing or cooperating with federal immigration law -- are a haven for undocumented immigrants and thus hotbeds for criminals and illegal activity that would otherwise be punished. Sessions even cited an academic study to prove his point.

“According to a recent study from the University of California, Riverside, cities with these policies have more violent crime on average than those that don’t,” he said, according to a Department of Justice transcript of the speech.

The problem? That study didn’t say that.

“There wasn’t actually any relationship between the passage of a sanctuary policy and that city’s crime rate,” Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien, one of the study’s authors, told Inside Higher Ed. “All of the data to date suggests that either there’s no relationship, which is what our study found, or there’s an inverse relationship.”

Gonzalez O’Brien, a political science professor at Highline College whose research focuses on immigration, as well the study’s other co-authors, wrote about their findings on The Washington Post’s “Monkey Cage” blog in October. The post was titled, bluntly, “Sanctuary Cities Do Not Experience an Increase in Crime.”

“I like doing this kind of research because I want to bring as much scientific evidence to bear on how we make public policy,” said Loren Collingwood, co-author of the study and an assistant professor of political science at UC Riverside. “Some cities did see higher crime rates [after becoming a sanctuary city], like St. Louis, for example. But some had no change, and many had lower crime rates. When you put all that together, it’s a wash.”

The study was also picked up by Fox News, which referenced the study when examining a drop in crime in Phoenix, which law enforcement credited to the city rescinding its sanctuary laws.

“A six-year study published last year by the University of California, Riverside, found ‘violent crime is slightly higher in sanctuary cities,’” the Fox article read. “It concluded there was ‘no statistically discernible difference in violent crime rates, rape or property crime across’ 55 cities studied.”

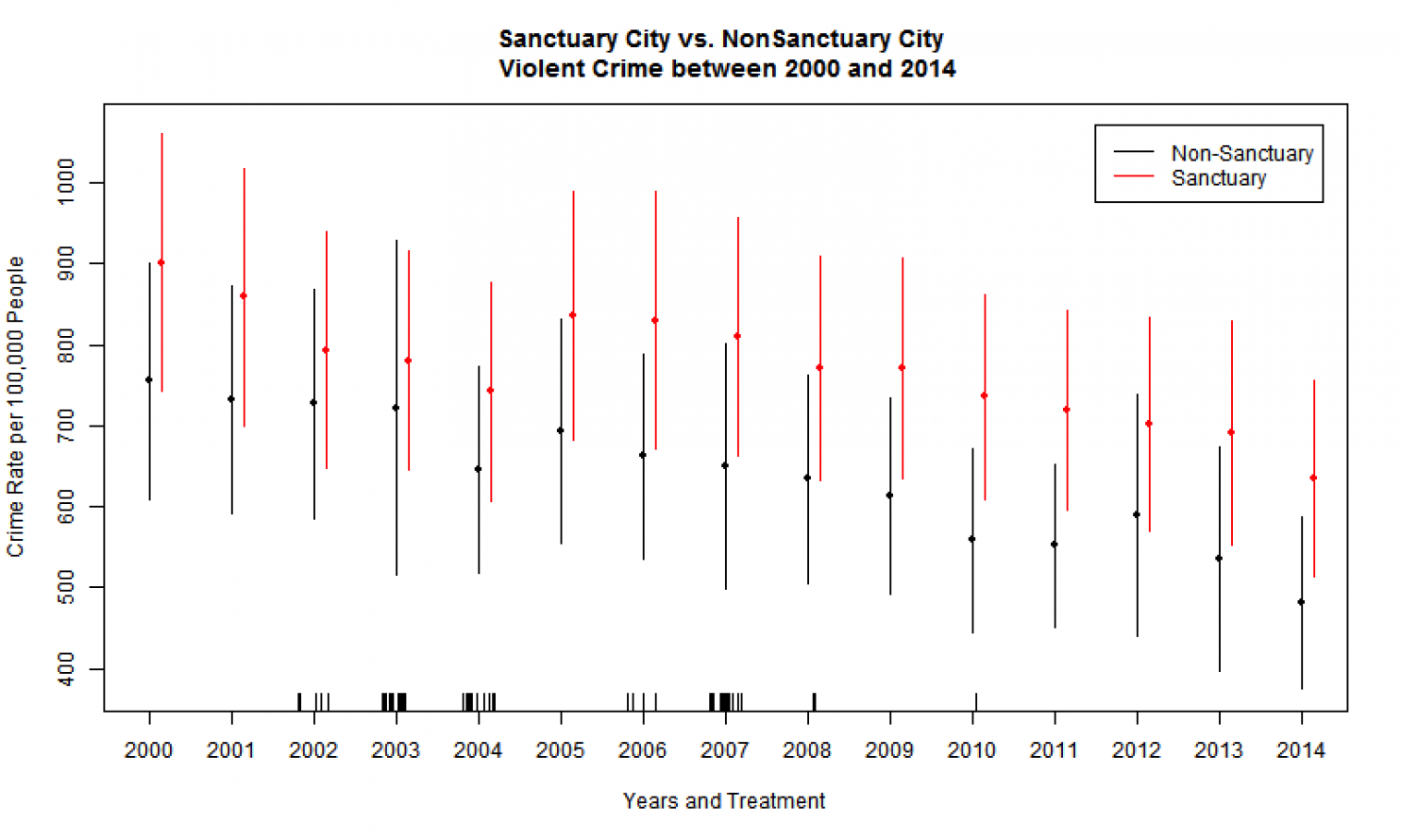

Both of those sentences are true, but that second sentence, Gonzalez O’Brien said, invalidates the first, which is why the study’s authors titled their Post piece so bluntly. But by starting its paragraph the way they did and not discussing the study’s error bands, which negate that first sentence, Fox’s article was misleading, he said.

“It’s pretty clear from the title of [our] piece what the findings were,” Gonzalez O’Brien said. Sessions, he added, went a step farther by not including any disclaimer about the lack of statistical significance in the crime rates at all. ( (In chart at right, all lines that could show an increased crime rate are within margin of error.)

“It’s pretty clear from the title of [our] piece what the findings were,” Gonzalez O’Brien said. Sessions, he added, went a step farther by not including any disclaimer about the lack of statistical significance in the crime rates at all. ( (In chart at right, all lines that could show an increased crime rate are within margin of error.)

A DOJ spokesman doubled down on Sessions’s use of the study, however, in a statement to The Las Vegas Review-Journal.

“The attorney general accurately cited data from a study that clearly showed that the violent crime rate was higher in sanctuary cities versus nonsanctuary cities. That is a fact and assertions to the contrary ignore that data,” Sessions spokesman Ian Prior said.

Gonzalez O’Brien wasn’t convinced.

“Those were not our findings,” he said.

“I believe that was deliberately done, that the attorney general is trying to push -- and that the Trump administration is trying to push -- that sanctuary cities are shielding criminals and have a higher crime rate.”

The Justice Department did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

Gonzalez O’Brien and Collingwood penned another piece for “Monkey Cage” about their study, this time pushing back against its misrepresentation.

“In short, we find no evidence that crime is higher in cities that become sanctuaries,” they wrote. “We hope that the attorney general will accurately state that finding in the future.”

Collingwood said that the political narratives around sanctuary cities can make research difficult and can skew public perception.

“One of the main problems with studying sanctuary cities is that people will say, ‘Oh, sanctuary cities have more crime,’ like a person out there would say something like that,” he said. “But a sanctuary city might become a sanctuary city because there was already high crime there, and they may have said, ‘Hey, let’s do something to get these people more trusting [of the police].’”

The concerns about Sessions’s misrepresentation go beyond an academic headache, though.

“We certainly do need to have a conversation about immigration, we certainly do need to have a conversation about doing something about the 11 million or so estimated undocumented immigrants in this country,” Gonzalez O’Brien said. “But having a conversation when you essentially have an administration that’s stirring up dirt toward this population is essentially impossible, and is going to make this task significantly more difficult.”