You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Missouri's state capitol

Missouri state government

Financial pain from the coronavirus pandemic is hitting the nation’s colleges and universities hard, and Northwest Missouri State University is no exception.

John Jasinski, president of the four-year institution, which enrolls more than 7,000 students and is located 100 miles north of Kansas City, Mo., has been dealing with serious challenges the crisis brought to the university’s budget.

Jasinski said he’s put off spending money where he can, on professional development, upgrading educational software and other areas, as the crisis brings unexpected costs such as the more than $4 million the public university is spending to refund students' room and board fees after classes were moved online.

But two weeks ago -- in what could be a harbinger of the pain coming soon to other universities around the country -- things got even worse.

Mike Parsons, the state's Republican governor, who is dealing with his own revenue problems as businesses shutter and unemployment skyrockets, announced $180 million in cuts in the budget for the current fiscal year, which ends June 30. Nearly half of that amount ($76.3 million) is being cut from the state contribution to community and four-year colleges.

Northwest Missouri State is losing $2.5 million, or nearly 9 percent of its annual revenue, with the cut heaped on top of struggles it already faces.

The university got some help late last week when it learned that its share of the $2.2 trillion federal stimulus will be $4.8 million. But only half of that amount will help the university’s budget, because the stimulus required that at least half be spent on emergency grants for students.

The $2.4 million left over won't even cover the cost of refunding room and board, much less other hits the university is taking.

And the state is almost certain to cut more next year.

“News of a withhold is never good, but certainly the timing … came at a very difficult time,” Jasinski said. He added that the university may have to spend less on help for first-generation students. “But we’re resilient and gritty.”

State Cuts Have Begun

Northwest Missouri State likely won't be an outlier in its financial pain, said Thomas Harnisch, vice president for government relations at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

“It could be a sign of things to come,” he said.

With uncertain prospects in Congress for even half the $500 billion the nation's governors say they need to stabilize budgets, many states face budget cuts. And they will look at slashing funds for public colleges.

"Higher education is often considered the balancing wheel of state budgets," said Harnisch. "And if history is any indication, higher education is going to be at the front lines of the economic fallout from coronavirus."

As Josh Goodman and Mark Robyn, senior officers with the Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal health initiative, noted in a recent blog post, the pandemic comes at an awkward time, as some states have already written the next fiscal year’s budget or were in the middle of determining it. States generally base their budgets on revenue projections conducted in January or February. But the crisis has sent budget writers in state capitols scrambling to get a handle on just how much tax revenue they’ll lose, and how much they’ll have to cut.

And higher education is already taking hits from state cuts. Expecting deep losses in revenue, New Jersey governor Phil Murphy last month froze $920 million in state spending for the remainder of the state's budget year, which ends Sept. 30, including $122 million for public colleges and universities. The cuts represent half the funding the colleges were supposed to get from the state in the next three months.

Rutgers University lost $73 million. The cut hurts, considering Rutgers will receive only $54 million from the federal stimulus package -- a figure a Rutgers spokeswoman called “woefully short.” Including the state cut, the university is slated to lose $200 million in just the next three months, including $50 million in room and board refunds, she said.

The university expects more state cuts in the next fiscal year.

Andrew Cuomo, New York's Democratic governor, had proposed increasing higher education spending by 3 percent earlier this year, including an expansion for the state’s free community college program. Now, the state is forecasting a drop in revenue this budget year, which started this month, according to Robert Mujica, New York's budget director. The state is working on announcing an initial $10 billion in budget cuts in the next few weeks, and could make more later in the year if the economy doesn’t improve.

“Everybody is going to be cut. How deeply is still to be determined,” said Freeman Klopott, a spokesman for the state budget office.

Without more federal aid for the state, the State University of New York system faces “potentially deep cuts to our academic programs and services,” Kristina Johnson, the system's chancellor, said in a statement.

On the other coast, a spokesman for the University of California system said it is hoping the state will be able to provide enough funding "to keep UC campuses operating at current service levels, especially due to the challenging economic conditions brought on by COVID-19." The system also is hoping the state will still make good on the $217.7 million increase the state's Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, proposed in January, before the epidemic worsened.

But Newsom said at a press conference two weeks ago, "The January budget is no longer operable … The world has radically changed since the January budget was proposed."

Widespread Financial Trouble

Other states are likely to be short on money as well.

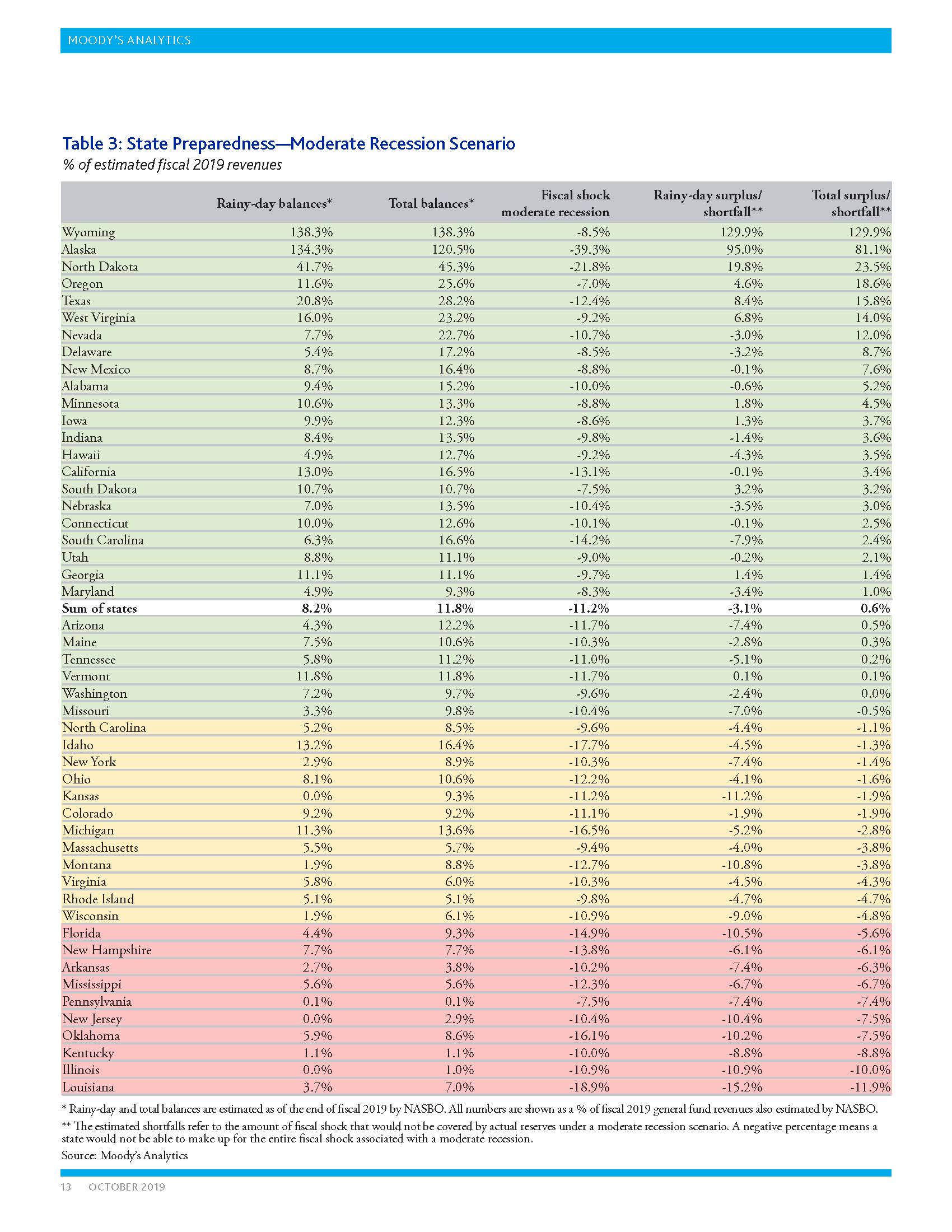

Just last October, states seemed to be in pretty good fiscal shape, according to an annual assessment by Moody’s Analytics on whether states have enough cash on hand to weather a recession without having to raise taxes or cut spending.

Only 10 states had so little money banked that they were “significantly unprepared” for even a modest recession, Moody's said.

But on top of the closure of businesses as states and cities have adopted social distancing regulations, gas and oil prices have dropped, and tourism has plummeted, while other states have been hurt by a reduction in trade particularly with Asian countries, Sarah Crane, an economist for Moody's, said in an interview.

Crane was still crunching the numbers on an updated report the credit ratings firm is expected to issue this week.

But she said the new picture isn’t pretty.

The report will say almost twice as many states are now unprepared for even the best-case scenario, in which social distancing requirements will last until the middle of the year.

The 10 least-prepared states last fall will still be in the crosshairs during a recession: Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania.

More than half the states are unprepared under a more severe scenario, said Crane, in which many businesses remain closed through the fall.

Higher Education on the Block

For a number of reasons, involving politics and the nuances of writing budgets, states that are forced to make cuts will look toward higher education.

“States don’t have a lot of control over what they can cut,” said Jeff Chapman, director of the state fiscal health project at the Pew Charitable Trust. “Where they cut ends up being a function of where they have less restrictions.”

K-12 funding in many states is protected by state constitutions. Programs like Medicaid receive matching funds from the federal government, so cutting there would mean losing federal dollars.

“The next biggest pot is higher education funding, and that’s the place states tend to go,” Chapman said.

Another factor that contributes to state slashing of support for higher education, said Liz McNichol, senior fellow at the progressive Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, is that lawmakers figure colleges can make up for the cuts by raising tuition.

But tuition increases stemming from state cuts during the last recession led to students being hobbled by more debt, as they took on a greater share of paying for higher education.

It was no surprise that Missouri looked to its community colleges and four-year institutions for so much of its budget cuts, said Paul Wagner, executive director of the state’s Council on Public Higher Education, an association made up of the presidents and chancellors of Missouri’s 13 public four-year institutions and the president of the University of Missouri system.

“Missouri has an unfortunate habit of turning to higher education when there are budget shortfalls,” said Wagner, former deputy commissioner at the Missouri Department of Higher Education and a former education budget and policy analyst for the State Senate.

In part, he said, that's because budget writers have assumed institutions can make up budget cuts by raising tuition.

“Cutting K-12 is very politically unpopular, of course,” and funding for those schools is being hit because the pandemic has forced the closure of the casinos that provide some state revenue.

Louisiana's economy was seen to be growing as recently as February, when John Bel Edwards, the state's Democratic governor, proposed increasing spending by $285 million this year. That included a $34 million boost for higher education institutions to help make up for cuts they suffered during the last recession, and another $6 million to expand the state’s scholarship program. Edwards also socked away hundreds of millions of dollars in a rainy-day fund.

While the state's reserves will help, they are the equivalent of just 3.7 percent of its revenues last year -- one of lowest ratios in the nation, according to Moody’s. In comparison, Wyoming’s reserve fund was the equivalent of 138 percent of its revenues, making it the best-prepared state in the nation for a recession.

As the state faces dropping oil prices, tourism and other hits, it’s unclear how much of a shortfall the state’s budget will have, said Steve Procopio, policy director of the Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana.

“We don’t know what’s really happening with the virus,” he said. “We’re waiting to see which way it goes. We don’t know if we’re looking at a $200 million gap or a $2 billion gap.”

But he predicted the state’s colleges and universities will probably face at least some cuts.

At the least, “we will no doubt abandon all proposed budgetary increases in higher education, as well as in every other area of the budget that does not relate to the COVID response,” Jay Dardenne, commissioner of the Division of Administration, which manages the state’s financial operations, said in a statement.

The funding formula for K-12 education, unlike higher education, is set in the state’s constitution. “The lack of constitutional protection is the major reason for higher ed’s exposure to budget cuts,” Dardenne said.

In addition, some parts of the state government, including the Department of Natural Resources, are funded by fees that can’t be used for other things, Procopio said.

“Health care is very tough to cut because there’s a health-care crisis. There’s a belief you just can't touch health care right now in the middle of a pandemic,” he said. “Higher education, by math, becomes a better target. Not because you don’t like higher education, but if revenue is falling, what do you do?”

If this sounds familiar, it’s because states cut higher education deeply during the last recession.

According to a 2017 analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, state funding for higher education hadn’t recovered from those reductions even a decade later.

When adjusted for inflation, funding by states for public two- and four-year colleges in 2017 was still $9 billion less than in 2008. Though states' revenues had returned to pre-recession levels, state spending per student was 16 percent lower than before.

The result was tuition at public four-year colleges across the nation rose by an average of $2,484, or 35 percent, between 2008 and 2017. It doubled in Louisiana and rose by more than 60 percent in Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia and Hawaii.

Meanwhile, attention is turning to whether Congress will include additional aid for states and higher education in another stimulus bill.

Education advocates were disappointed by the $14 billion for higher education institutions in the last stimulus. A coalition of groups, including associations representing two- and four-year institutions, wrote Congress last week to say they needed an additional $46.6 billion to make up for costs like returning room and board and lost revenue from what the groups estimated would be a 15 percent decline in enrollment this fall.

Meanwhile, governors also have said the $150 billion in aid to states and local governments in the last stimulus package wasn’t enough to prevent large cuts. On Saturday, the National Governors Association wrote congressional leaders, saying, "in the absence of unrestricted fiscal support of at least $500 billion from the federal government, states will have to confront the prospect of significant reductions to critically important services all across this country, hampering public health, the economic recovery, and -- in turn -- our collective effort to get people back to work."

The group's chairman, Maryland governor Larry Hogan, said at a press conference last week that without more congressional aid, "There's going to be massive budget problems for every state in America." Last Friday Hogan froze his state's spending, except for coronavirus-related expenses and payroll, saying Maryland is facing a $2.8 billion budget shortfall.

However, Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. Senate are deadlocked over the next package. Republicans want it to focus on providing $250 billion of aid to small businesses. But Democrats want to add $250 billion of aid for hospitals and state and local governments. Last Thursday, Senate Democrats blocked the Republican proposal. Then Republicans blocked the Democrats' proposal.

The Hill reported that Senate Republicans do not want to take up negotiations on the next package until next month. On Saturday, Politico reported that Republican leaders are vowing to keep opposing the Democrats' plan. “Republicans reject Democrats’ reckless threat to continue blocking job-saving funding unless we renegotiate unrelated programs which are not in similar peril,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said in a joint statement.