You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Biden administration’s plans to forgive student loans and lower payments for borrowers have hit a roadblock in the federal courts. Lawyers for the administration want the Supreme Court to clear the way.

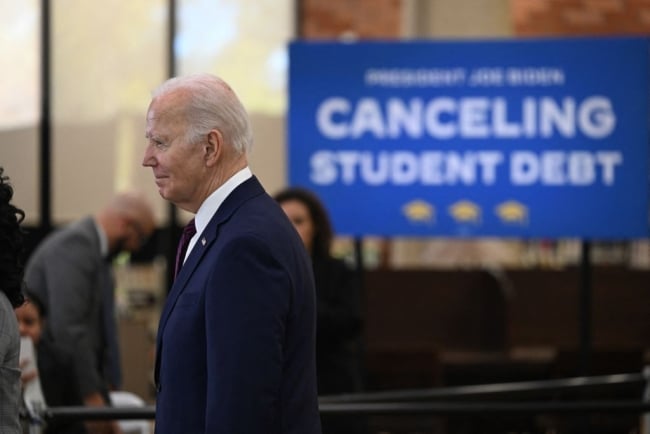

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

A federal appeals court on Monday declined to clarify its order, issued earlier this month, that put the Biden administration’s new student loan repayment plan on hold, leaving borrowers in limbo and raising concerns about the Education Department’s authority to forgive student loans.

Monday’s one-sentence order from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit is the latest twist in a legal battle over the Education Department’s ability to forgive student loans and change the repayment terms for borrowers—a fight that will likely end up at the Supreme Court and could potentially shut off a decades-old pathway to debt relief.

In an order issued earlier this month, the Eighth Circuit blocked the Biden administration from forgiving any loans or interest for borrowers enrolled in the repayment plan known as Saving on a Valuable Education, or SAVE, which was designed to make payments more affordable and offer some borrowers a quicker pathway to forgiveness. That included changing the payment calculation so that low-income borrowers have payments of $0 a month. Prior to the court order, about four million borrowers were benefiting from this change.

Missouri and six other Republican-led states challenged SAVE, arguing that it exceeds the department’s authority and amounts to just another version of the broad-based debt-relief plan that the Supreme Court struck down last summer. These seven states are one of two groups suing the Biden administration over the plan. In the other lawsuit, led by Alaska, an appeals court allowed the SAVE plan to move forward—an order nullified by the Eighth Circuit decision.

Lawyers for the Biden administration want the Supreme Court to overturn the injunction, arguing that the states lack standing to challenge the plan and that the order was “vastly overbroad” and “upends” the status quo for borrowers who have already been making payments based on the terms of the SAVE plan. (Temporary injunctions are supposed to preserve the status quo while the courts consider the merits of a case.)

The injunction, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar wrote in a filing, is “causing significant and irreparable harm to borrowers” as well as “intense confusion.” The nearly eight million borrowers enrolled in SAVE have been placed in forbearance, which essentially pauses their payments while litigation continues. Borrowers who want to enroll in SAVE can fill out a PDF application, but the department has turned off the online form. Loan servicers have temporarily paused their processing of SAVE applications, the department has said.

The Eighth Circuit also prevented the department from carrying out provisions to lower payments—which means that borrowers on the plan would have seen higher payments if their accounts weren’t put on hold.

But beyond the direct implications to SAVE, which was finalized last year, the ruling also appears to affect borrowers who are on income-contingent or income-driven repayment plans dating back 30 years. Congress passed a law allowing the education secretary to craft a repayment plan that bases a borrower’s payments on their income in 1993, and the first plan launched in 1994.

The Biden administration has said that the injunction also bars loan forgiveness for borrowers enrolled in any income-driven repayment plan, not just SAVE. That’s because the final regulations that created the plan also included some changes to the other income-contingent repayment plans. About 10.5 million borrowers with loans totaling $582.8 billion were enrolled in SAVE, the Obama-era repayment plan known as PAYE or the income-contingent plan, according to the latest federal data.

Lawyers for the Biden administration quickly sought to clarify and narrow the scope of the injunction. “For example, borrowers enrolled in an [income-contingent repayment] plan may become eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness,” they wrote. “But the injunction could be understood to prohibit forgiveness because those borrowers’ loans are governed at least in part by the final rule. The department does not believe, however, that the court intended to sweep so broadly.”

The Eighth Circuit didn’t say whether it did in fact intend to “sweep so broadly” when it denied the Biden administration’s motion to clarify. The administration is now making its case to the Supreme Court. If the high court declines to overturn the injunction, Prelogar wants the justices to take up the case and hear oral arguments in November.

“The Eighth Circuit fundamentally erred by issuing a sweeping universal injunction based on a demonstrably erroneous theory of standing and without meaningful analysis of the statutory text,” Prelogar wrote in a filing Tuesday. “Yesterday, the Eighth Circuit made clear that the injunction extends even more broadly to forgiveness under regulations adopted in 1994, disrupting the settled expectations of borrowers who have made payments for years or even decades.”

The court battle and disruptions to SAVE have left borrowers reeling. They’re anxious about what’s going to happen and are trying to figure out how to proceed, said Betsy Mayotte, founder of the Institute of Student Loan Advisors, a nonprofit that provides free student loan advice. That includes recent college graduates who are just preparing to start paying back their loans and deciding the best plan for them; they could likely qualify for lower payments under SAVE, but the department isn’t processing applications for the plan.

“Nothing like this has ever happened before,” she said. “This is an incredibly challenging time. We just don’t even know what to tell people to do, because this is uncharted territory.”

Mayotte said this is one of the worst moments in her 20-year career in the student loan industry.

“We’re hearing from people who were on SAVE, and they made financial decisions in their lives based on the payment amount and bought houses,” she said. “They might not be able to afford their mortgage if SAVE goes away and their payment goes up.”

Broader Questions About Forgiveness

Prelogar, the solicitor general, wrote in a court filing last week that “for good reason,” no court has ever questioned the department’s ability to forgive loans through income-contingent repayment plans. Congress first authorized them in 1993 but left the specifics of the program’s design up to the education secretary. The statute requires that a borrower’s annual payments be based on their income and that payments should be made over a period of time not exceeding 25 years.

Congress didn’t say what should happen to a borrower’s remaining student loans after 25 years of making payments, but education secretaries have interpreted the statute to allow them to discharge an outstanding balance. That interpretation has gone unchallenged in the courts until now.

States challenging SAVE argued that previous income-contingent plans “unlawfully authorized forgiveness, but hardly anybody qualified.” The difference with SAVE, they said, is that more borrowers are expected to benefit and the cost will be high—$475 billion over 10 years, according to one estimate. (The Biden administration puts the price tag closer to $156 billion over 10 years.)

The states are not alone in their arguments. The New Civil Liberties Alliance, a nonprofit that has sued the Biden administration over its student loan policies, filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court, arguing that the 1993 law doesn’t give the department “unfettered discretion” in designing a repayment plan based on a borrower’s income.

Michael Brickman, adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, said the SAVE plan is illegal and “a sneaky way to get loan forgiveness without calling it that.”

Brickman said that the income-contingent plans were not intended to become a pathway to forgiveness when Congress created the authority; instead, they were meant to “create more flexible options.”

Brickman and other opponents of SAVE are not troubled by the injunction or the broader implications of the court order. ”Forgiveness under the previous plans should have been challenged,” he said. “Some people are surprised at the opposition to this. The administration knows what it is doing is illegal and they are doing it anyway, and that deserves a very forceful response from the courts.”