Free Download

Colleges and universities have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on technology they believe will improve student outcomes and simplify administrative tasks. Educational technology companies continue to demolish investment records on a quarterly basis. With all this money raised and spent under the guise of improving postsecondary education, the 2015 Inside Higher Ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology suggests that many instructors believe the gains in student learning justify the costs -- even if the results are perhaps less significant than desired.

Inside Higher Ed partnered with Gallup to ask faculty members and academic technology administrators to share their thoughts on this and other ed-tech issues in the news. A copy of the survey results, based on responses from 2,175 faculty members and 105 administrators, can be downloaded here.

Inside Higher Ed's 2015 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

On Nov. 12, Inside Higher Ed's Scott Jaschik and Carl Straumsheim conducted a webinar analyzing the survey's findings and answering readers' questions. To view the webinar, please click here.

The survey was made possible in part by financial support from Mediasite, the Learning House and Academic Partnerships.

Highlights from the report include:

- The gap between administrators and faculty members widens as instructors -- including those who have taught online -- become more negative about the quality of online education, especially compared to face-to-face instruction.

- Nearly two-thirds of faculty members believe detection software can stop students from plagiarizing, but less than one-quarter believe students have a full understanding of what plagiarism actually is.

- Faculty members are skeptical about new academic programs that combine face-to-face instruction with massive open online courses, fearing the model threatens traditional faculty roles.

- Administrators and faculty members overwhelmingly say textbooks and other course materials are too expensive, and that instructors should seriously consider costs when assigning readings.

- A majority of faculty members are concerned about attacks on scholars for their comments on social media and feel that colleges must do more to encourage civil discourse online. See related story.

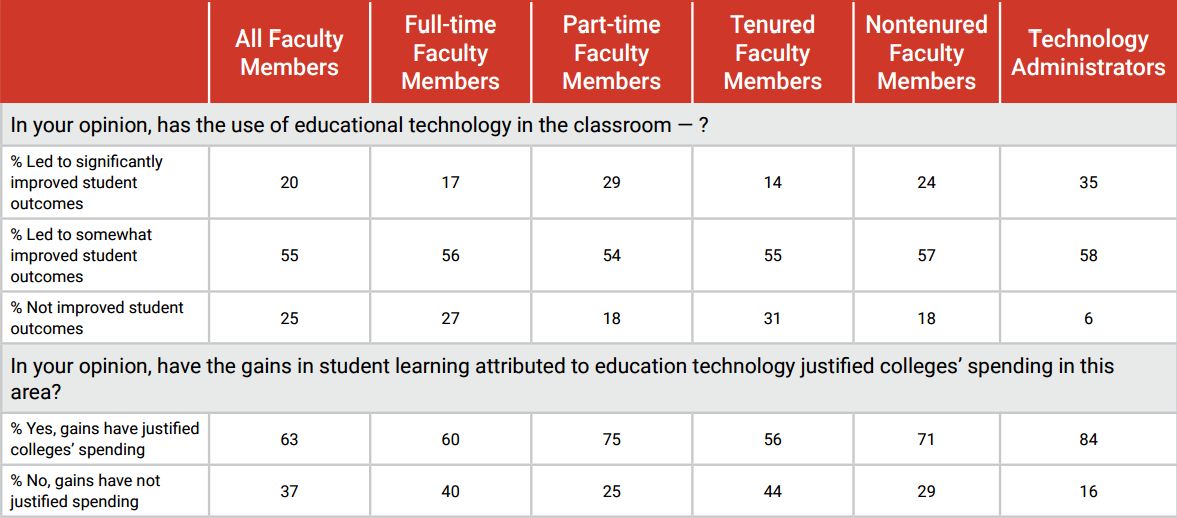

New to this year’s survey is a pair of overarching questions about whether administrators and faculty members have seen improvements in student outcomes and, as a follow-up, if those results justify the spending.

To answer the second question first -- yes, 63 percent of faculty members and 84 percent of administrators surveyed say the portion of their institutions’ budgets that has gone toward ed tech is money well spent. But whatever increases they are seeing in student outcomes don’t appear to be greater than expected. Only 20 percent of faculty members and 17 percent of administrators say the gains have been significant, though a majority (55 percent and 58 percent, respectively) say they have seen a moderate improvement. One-quarter of faculty members say there have been no improvements at all.

One of the largest ed-tech investments for many colleges -- online courses -- continues to be one of the most divisive. Only 17 percent of faculty members say for-credit online courses taught at any institution can achieve outcomes that are at least equivalent to those of in-person courses, while 53 percent disagree or strongly disagree. Faculty members are even more negative about online versions of courses they teach themselves, with 59 percent hypothesizing that an online course couldn’t match the quality of face-to-face instruction.

Since last year’s survey, faculty members in general have actually become more negative toward online courses. A year ago, 26 percent of respondents said online courses can produce outcomes equal to in-person courses, and those in disagreement made up less than a majority. This year’s drop may be the result of a wording change rather than a growing anti-online sentiment, however. Last year, the survey asked respondents to consider the quality of “online courses,” while this year’s edition specified “for-credit online courses.”

Among administrators, the numbers are flipped. Nearly two-thirds of those surveyed (62 percent) say online courses taught at any institution feature the same quality as in-person courses. Asked specifically about online courses offered at their own institution, the number jumps to 88 percent.

Faculty members who have never taught online continue to influence the overall results, with between 11 and 15 percent of respondents reporting a positive view of the quality of online courses no matter who teaches them. The same can’t be said for faculty who have experience teaching online. They are similarly suspicious about online courses taught at any institution -- only 28 percent (down from 41 percent last year) say those courses can rival in-person courses -- but the share grows steadily as they are asked about courses coming from their institutions, their disciplines and themselves. In response to that last question, a majority of faculty members who have taught online (56 percent) say those courses are at least as good as the ones they teach in person.

The institutional and personal demographics of the survey respondents remain largely the same. About one-third of faculty members (32 percent) say they have taught an online course, virtually unchanged from the 33 percent who said the same last year. Just about half of them (49 percent) are tenured, and about three-quarters (76 percent this year, 78 percent last year) work full time for their institution.

Also unchanged are the indicators that -- to faculty members -- mark a high-quality online course and the areas where faculty members say the mode of delivery falls short. No more than one in 10 faculty members say online courses are better than in-person courses when it comes to delivering course content, reaching at-risk and exceptional students, and interacting with students in and outside of class, among other factors.

The divide between faculty members and administrators is again on display. Faculty members are more likely to say online courses provide the same or lower quality in these areas; administrators, the same or higher.

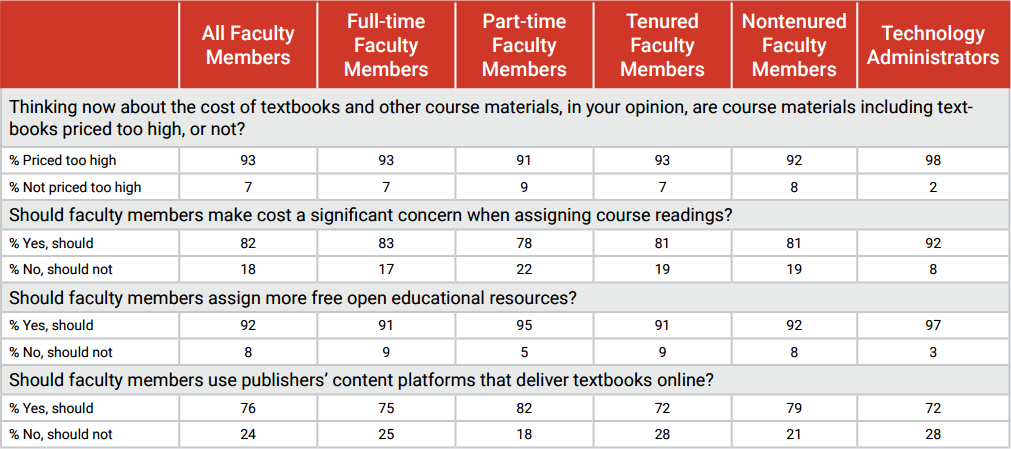

Textbook Prices

Just in time for back-to-school shopping, an NBC News analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data this August found textbook prices have increased 1,041 percent since 1977. Some individual examples serve to highlight that increase. Earlier this year at the University of Michigan at Flint, for example, the library discovered a $400 textbook assigned in an upper-level chemistry course.

Faced with this additional expense, students often opt for used or rental books to avoid paying the full price. In the worst-case scenario, they may not obtain the course materials at all, potentially setting themselves up to do worse in the course than those who can afford them. Colleges, meanwhile, are experimenting with several alternatives to reverse the trend, including free open educational resources and degree programs with no additional textbook costs.

Faculty members and administrators strongly support these and other efforts to reduce the price of course materials, according to the survey responses. Virtually all respondents (93 percent of faculty members and 98 percent of administrators) say course materials are too expensive, and an overwhelming majority (82 percent, 92 percent) say cost should be a significant concern when instructors assign course readings.

Open educational resources rate as one popular strategy, with 92 percent of faculty members and 97 percent of administrators saying instructors should assign more of them. Still, past research has suggested many faculty members haven’t heard of OER or don’t know where to discover open content.

David Wiley, chief academic officer of Lumen Learning, said the report builds on previous findings about OER.

“These new data from Gallup make it clear that faculty understand the problems with textbooks and other commercial course materials and are very positive on OER,” Wiley said in an email, adding that he expects more colleges to create zero-textbook-cost degrees or offer OER in introductory courses. “Both moves significantly decrease students’ cost to graduate while increasing faculty’s pedagogical flexibility.”

Even traditional publishers get good news: 76 percent of faculty members and 72 percent of administrators say instructors should use publishers’ online content platforms as opposed to traditional print textbooks.

Plagiarism-Detection Software

Plagiarism-detection software came under renewed scrutiny this summer as two tests conducted eight years apart suggested Turnitin, a popular choice for many colleges, missed more than one-third of plagiarized sources.

Organizations for writing instructors have long criticized plagiarism detection software for turning up false positives -- in other words, that the software is too sensitive, falsely accusing students of not citing sources. The tests, conducted by Susan E. Schorn, a writing coordinator at the University of Texas at Austin, highlighted a new problem: false negatives.

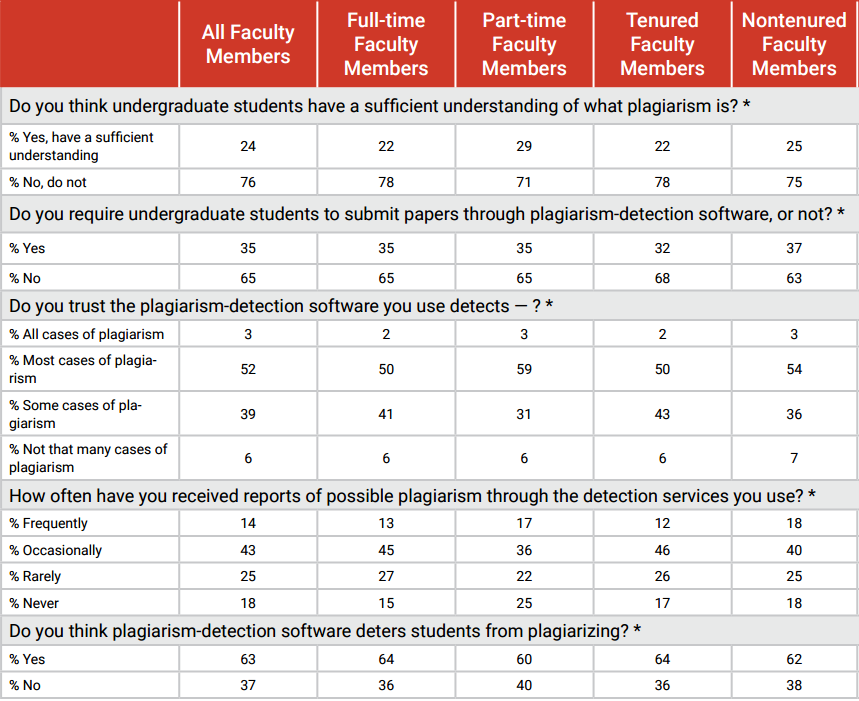

Faculty members continue to trust the software to identify cases of plagiarism, however, even if the software isn’t perfect. Nine out of 10 faculty members (or 91 percent) say they trust the software to catch most or some cases of plagiarism, and an additional 3 percent say the software catches it all. Only 6 percent say they believe the software doesn’t catch much of the unoriginal writing submitted by students.

Faculty members also believe in plagiarism-detection software as a way to deter students from claiming other people’s writing as their own. While only 35 percent of faculty members require students to submit papers through plagiarism-detection software, 63 percent say the software works as a deterrent.

In an email, Schorn said she found the survey results “fascinating,” but also “amusing.” She questioned how faculty members justify their support for plagiarism-detection software when more than three-quarters of those surveyed (76 percent) said they don’t believe students have a sufficient understanding of plagiarism.

“A fair number of faculty evidently think [the software] can deter students from plagiarizing, even though students don’t actually understand what plagiarism is,” Schorn wrote. “I wonder how they see that working. Perhaps it’s something like abstinence-only sex ed?”

‘MOOC-like’ Programs

Since the Georgia Institute of Technology in spring 2013 introduced its low-cost online master’s degree in computer science -- a partnership with MOOC provider Udacity -- more universities have explored using MOOCs as a gateway to a degree. This year alone, Arizona State University and edX launched Global Freshman Academy, which will soon offer a year’s worth of credit through MOOCs; the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign announced an M.B.A. program where much of the course content is available on Coursera; and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology unveiled an alternative path to enrollment in its supply chain management program that begins with a semester taking MOOCs.

These initiatives are, in other words, “MOOC-like.” The universities may offer one version of the courses that could be described as massive and open, but in order to earn a degree, students eventually have to apply, be accepted and pay tuition.

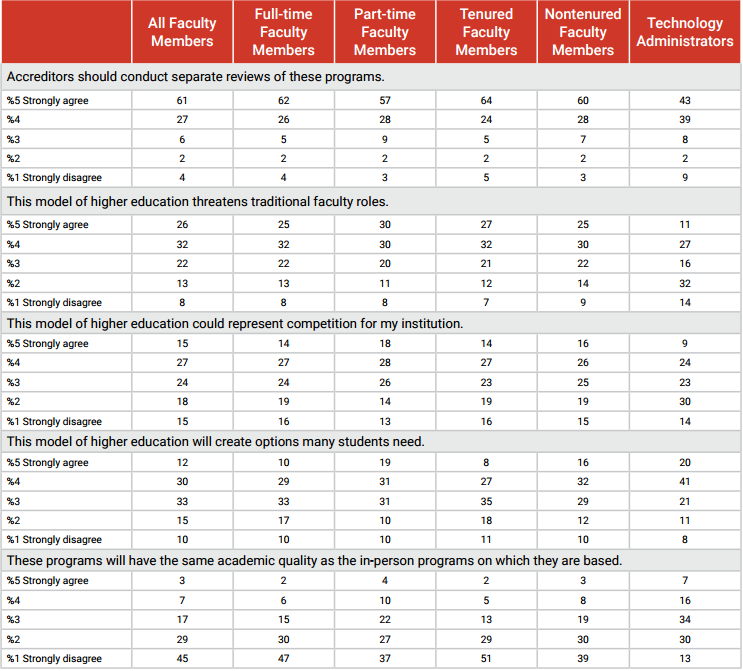

Some of those programs have yet to launch, and the universities are treating them as pilots and experiments. Faculty members and administrators, meanwhile, are approaching them with uncertainty.

About half of surveyed faculty members (58 percent) say MOOC-like programs threaten traditional faculty roles, but 42 percent also say the programs will create options many students need. Administrators, in comparison, are less concerned about the impact on faculty roles (38 percent) and more optimistic about using the programs to give students more options (61 percent).

What faculty members and administrators agree on, however, is that the programs won’t have the same quality as the in-person programs they are based on. Only 10 percent of faculty members say the programs will, as do 23 percent of administrators. Both groups of respondents (88 percent and 82 percent, respectively) say accreditors should review the programs separately.