Free Download

The proportion of college instructors who are teaching online and blended courses is growing. So is their support for using technology to deliver instruction.

But their belief in the quality and effectiveness of online courses and digital technology isn’t keeping pace.

Those are among the findings -- conflicting and confounding, as is often the case -- of Inside Higher Ed’s 2018 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology, published today in partnership with Gallup.

The survey solicits the views of 2,129 instructors and 206 digital learning leaders on a wide range of topics related to how technology influences their teaching and work with students. The survey offers results that will probably satisfy (and agitate) the most optimistic booster, and the biggest skeptic, of using technology to expand the reach of college-level teaching and learning while also improving its impact.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2018 Survey of

Faculty Attitudes on Technology was

conducted in conjunction with

researchers from Gallup. You may

download a free copy here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys

key higher ed professionals on a range

of topics.

On Tuesday, Nov. 27, at 2 p.m.

Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present

a free webcast to discuss the

results of the survey. Register

for the webcast here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of

Faculty Attitudes on Technology

was made possible in part with

support from Mediasite, Pearson,

Portfolium and VitalSource.

But like most attempts to suss out impressions on complex topics, the survey is most helpfully read as showing both modestly increasing adoption of many forms of classroom technology, as well as consistent challenging of whether those innovations are making a difference and how they might be improved. Academics are, after all, trained to think that way.

Among other highlights of the 2018 survey:

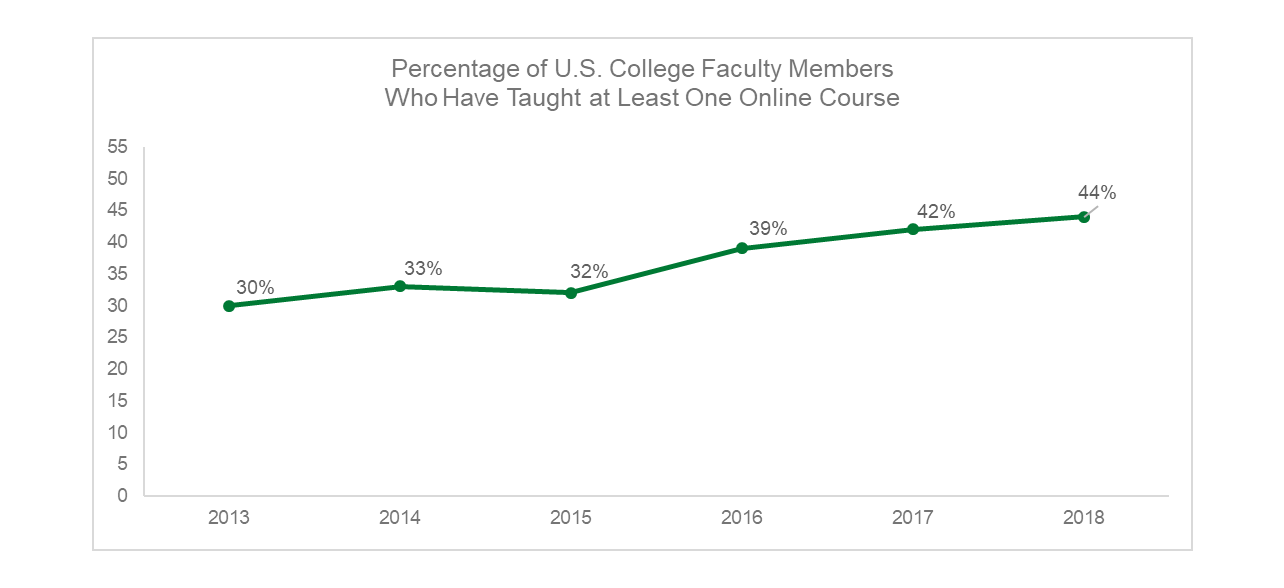

- Forty-four percent of instructors said they had taught an online course, up from 42 percent last year and 30 percent in 2013. (Thirty-eight percent said they had taught a blended course.)

- Professors who have taught online overwhelmingly say the experience improved their teaching and made them more likely to experiment with new approaches.

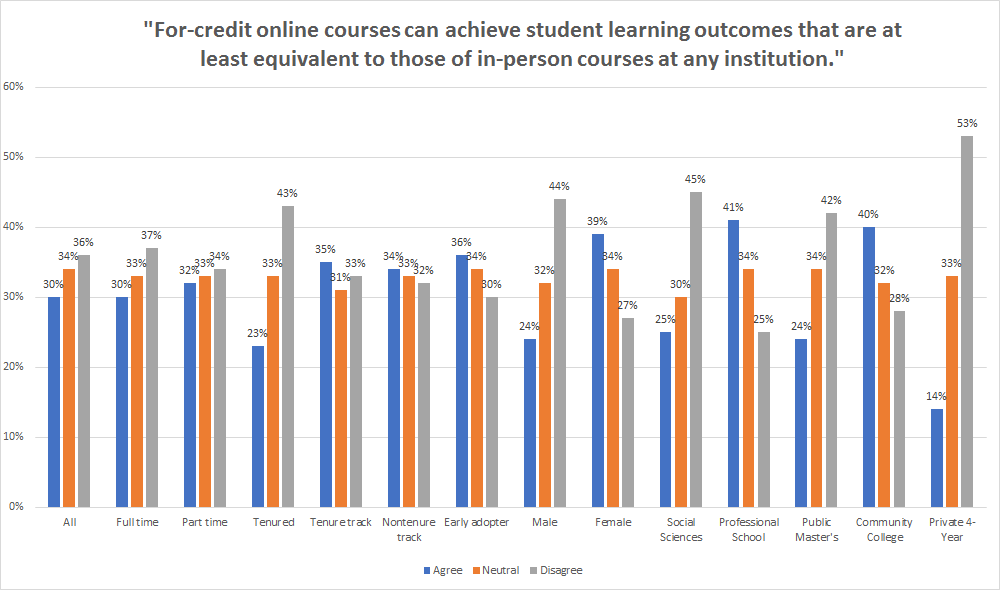

- Three in 10 instructors (30 percent) said they believe online courses can achieve student outcomes comparable to those of face-to-face courses, down slightly from 33 percent last year. And professors are more likely to disagree than to agree that using digital tools can lower the per-student cost of instruction without diminishing quality.

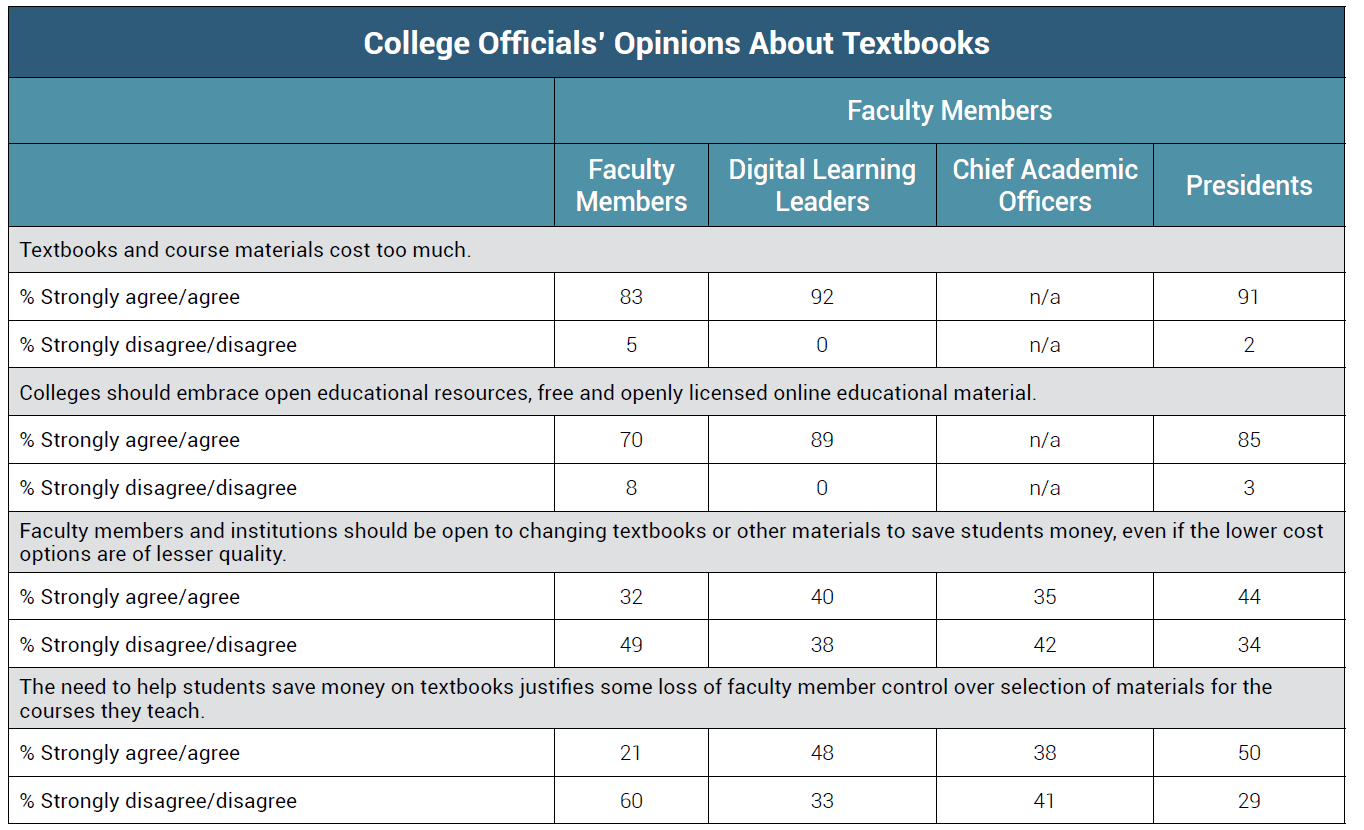

- Instructors and digital learning leaders alike overwhelmingly believe textbooks are too expensive and support the use of open educational resources and other low-cost alternatives. But their support only goes so far: professors generally reject the idea that saving students money justifies the loss of faculty control over course material selection or shifting to lower-quality options.

What Are Professors Actually Doing With Technology?

Much of the survey explores faculty views about technology and its role in learning. But the study also provides some useful data about their interaction with and use of technology.

First and foremost, while many colleges and universities are expanding their online footprints to try to provide more options for students and enroll more of them at a time when traditional enrollments are stagnating or shrinking, more faculty members are teaching online.

As seen in the table below, the proportion of instructors who say they have taught at least one online course rose to 44 percent, up from 42 percent last year and from 30 percent five years ago.

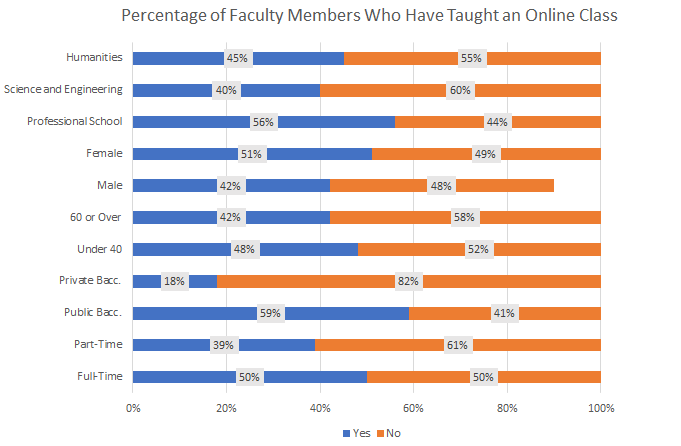

Full-time instructors (50 percent) are likelier than their part-time peers (39 percent), public college faculty members (47 percent) likelier than those at private institutions (29 percent) and female professors (51 percent) likelier than men (42 percent) to have taught online. Selected breakdowns are seen in the table below.

The number of instructors who have taught a blended or hybrid course -- one that mixes in-person and online components -- is growing slowly but steadily, too, edging up from 36 percent last year to 38 percent this year. About three-quarters of those who have taught a blended course said they were involved in designing the course.

(Inside Higher Ed and Gallup asked a greatly expanded set of questions this year about instructors' experiences designing those courses and working with instructional designers to do so. Those who had worked with instructional designers had a very favorable view of their work -- but a surprisingly small proportion of instructors said they had done so. A separate article on those results can be found here.)

"The increase in the share of faculty teaching in online or hybrid format is striking, if not surprising given the parallel increase in the number of students participating in online and hybrid courses (based on Babson and other sources)," Martin Kurzweil, director of educational transformation at Ithaka S+R, said via email. "Both factors speak to the growing 'normalization' of online and hybrid modalities -- although it’s still the experience of a minority, online and hybrid learning is no longer highly concentrated in a few institutions."

Last year's survey saw a marked upturn, to 33 percent from 19 percent the year before, in the proportion of instructors who agreed that "for-credit online courses can achieve student learning outcomes at least equivalent to those of in-person courses at any institution."

Gallup researchers said at the time that a change made in the order of the 2017 survey's questions may have contributed to that sharp increase. As Gallup's Jeff Jones explains, "the last two years we asked the [questions about outcomes] after we asked about their experiences [with online teaching]. So conceivably asking them about their experiences could make them answer questions about online education more positively."

In this year's survey, using the same order as last year's, the proportion of professors agreeing with that statement dipped slightly, to 30 percent (36 percent disagreed with the statement, and 34 percent were neutral). The fact that this year's result is roughly comparable to last year's, Jones said, suggests that this level of support is probably stable. (Three-quarters of digital learning leaders agreed with that statement.)

Professors were slightly more likely to believe in the effectiveness of online learning in their own institutions and classrooms as opposed to others’. Thirty-eight percent of instructors said for-credit online courses could achieve comparable learning outcomes "at my institution," and 35 percent said that was the case "in my department or discipline" and "in the classes I teach."

Differences were significant among different types of faculty members.

Those who have taught online were likelier than those who haven't (39 percent versus 24 percent) to agree with that statement about courses "at any institution," and the gap between those groups widened as the circle narrowed. Fifty-four percent of instructors who have taught online agreed that online courses "in my department or discipline" produced equivalent outcomes to face-to-face classes, while just 20 percent of professors who hadn't taught online thought so, for instance. And the proportions were 58 percent and 15 percent, respectively, "in the classes I teach."

Larger proportions of instructors at community colleges (40 percent) and public four-year colleges (39 percent) expressed confidence in the relative effectiveness of online courses "at any institution," compared to just 21 percent of professors at private comprehensive universities and 14 percent at private four-year colleges. Female faculty members are significantly likelier than men (33 percent versus 24 percent) to believe online courses can be at least as effective, and professional school instructors are the most likely (41 percent) and social science instructors the least likely (25 percent) to think so.

Asked to rate the effectiveness of for-credit online courses on 11 classroom objectives, faculty members were more likely to rate them as less effective than face-to-face courses on every one -- though majorities credited them as being as effective as in-person courses in a few areas, including grading and communicating about grading (66 percent said "as effective") and communicating with their college about logistical and other issues.

In more fundamental areas, though, online courses did not fare well. Eighty percent of instructors said digital courses were less effective than face-to-face classes in their ability to reach "at-risk" students, and 65 percent said the same about "rigorously engag[ing] students in course material" and ability to maintain academic integrity (60 percent).

Instructors who've taught online had more favorable opinions about the effectiveness of online learning than did their peers, but they still rated face-to-face courses higher in most cases. The question on rigorously engaging students in course materials is a good example: while 77 percent of those who had never taught online said online courses were less effective than in-person courses and 21 percent said they were as effective, 51 percent of online instructors said the courses were less effective on engaging students in the material, while 44 percent said they were as effective.

Professors may question whether online learning is improving their students' educational experience, but those who have taught online express confidence that doing so has made them better instructors.

Three-quarters (74 percent) of faculty respondents who have taught online said teaching such courses helped them "develop pedagogical skills and practices that have improved" their teaching.

Asked how, more than six in 10 said online experiences had made them think more critically about ways to engage students with content (68 percent), make better use of multimedia content such as video and audio (65 percent), use their learning management system better (61 percent) and experiment more and make changes to try to improve their students' learning experiences (60 percent).

About two-thirds of instructors who had converted a face-to-face course to a blended or hybrid format said they lectured less in the converted course, and a majority (54 percent) said they had incorporated more active learning techniques in the new iteration of the class.

Kurzweil of Ithaka S+R said the findings about improved teaching "seem to me like an effective argument that faculty ambassadors could use to encourage their colleagues to participate in online and hybrid learning."

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, described it as "troubling" that "even after a 10-fold increase in the number of online students [and] strong beliefs that teaching online makes you a better teacher … faculty remain skeptical about online education. Faculty are showing increased support for the use of instructional technology -- but not if it is to provide a course at a distance."

The Role of Technology, Real and Promised

Unpacking explanations for continued doubts about the effectiveness of online learning even as instructors' experience with it increases isn't easy, but the survey offers some clues.

Despite the stereotype, faculty members are not technology antagonists, at least in their own telling. Fifty-five percent of respondents to this survey describe themselves as "someone who typically adopts new technologies after seeing peers use them effectively," a full third (33 percent) say they are an "early adopter of new educational technologies" and only 12 percent say they are "disinclined to use educational technologies."

Three-quarters say they fully (32 percent) or somewhat (43 percent) support the increased use of educational technologies, while only 11 percent answer to the contrary.

When those who describe themselves as technology supporters are asked why that's the case, the three top answers were that they like experimenting with new instructional methods and tools (60 percent), they believe their students learn better when engaged with effective tech tools (58 percent) and they have had success with ed tech in the past (57 percent).

When the much smaller number of professors who said they don't support increased use of technology were asked why that's so, their top answer (67 percent) suggests a strong philosophical opposition: "I am confident that instruction delivered without using technology most effectively serves my students." Smaller numbers cited too much corporate influence (44 percent) and loss of faculty control (40 percent).

Answers to another set of questions show that advocates for technology in the classroom have probably overpromised or otherwise overplayed their hand in trying to win faculty approval.

Some campus administrators (egged on by tech company partners) have suggested that using technology can lower the per-student costs of instruction without lowering quality -- and most professors aren't buying it.

More than half of respondents (51 percent) disagree that digital tools can bring down instructional costs without impairing quality, while just 24 percent agree. (Half of digital learning leaders agree with that statement.)

And strong majorities of professors support statements that "administrators and vendors who promote the use of technology in delivering instruction":

- "exaggerate the potential financial benefits" (65 percent agree or strongly agree)

- "play down the risks to quality" (70 percent); and

- "do not fully appreciate the upfront costs required to develop high-quality online or blended offerings" (70 percent)

Faculty members who have taught online largely share those opinions, and even a majority of digital learning leaders who responded to the survey agree with the statements about exaggerating financial benefits (51 percent) and failing to appreciate the costs (61 percent). More disagree than agree with the statement about the risks to quality.

The other way in which college and university leaders may be undercutting their own attempts to build faculty buy-in for instructional innovation is in their failure to nurture and reward it.

Asked how well (or not) their institutions support professors' online teaching and course development, the answer generally was: not much. Small majorities of instructors agreed that their colleges provide "adequate technical support" for creating (50 percent) and teaching (53 percent) online courses -- important fundamental backing, of course.

But professors panned their institutions on a range of other ways they might provide support. To list a few:

Compensate fairly for online instruction? Thirty-four percent yes, 37 percent no.

Reward contributions to digital pedagogy? Thirty percent yes, 38 percent no.

Reward teaching with technology in tenure or promotion decisions? Twenty-four percent yes, 45 percent no.

Troubles With Textbooks

Do college textbooks cost too much? Is that even a question anymore?

Professors have no doubt: 83 percent of respondents agree (58 percent strongly) that "textbooks and course materials cost too much." They join 91 percent of digital learning leaders asked in this survey and 91 percent of college presidents queried in Inside Higher Ed's survey of campus leaders in March.

A solid majority of faculty members (70 percent) also join campus administrators in endorsing one increasingly popular solution to the textbook price problem: open educational resources (OER), the freely accessible and openly licensed digital curricular materials that many institutions, states and foundations are embracing. Some institutions, especially community colleges, are trying to build entire degree programs on OER materials, with the goal of driving down nontuition costs and spurring degree completion by reducing the number of students who forgo buying their course materials.

But the most recent data on faculty usage of OER, published last winter by the Babson Survey Research Group, showed both significant growth but modest overall usage of OER textbooks, with the proportion of instructors adopting open textbooks rising to 9 percent in 2016-17 from 5 percent in 2015-16. (A new version of the group's study is due in the coming weeks.)

The survey offers some insights into why professors' philosophical embrace of lower textbook costs and of OER as a solution has yet to translate into widespread adoption. Two words: quality and control.

Less than a third of professors (32 percent) agree that "faculty members and institutions should be open to changing textbooks or other materials to save students money, even if the lower cost options are of lesser quality." Roughly half (49 percent) disagree.

And just one in five (21 percent) endorse the statement that "the need to help students save money on textbooks justifies some loss of faculty member control over selection of materials for the courses they teach." A full 60 percent disagree.

As seen in the table below, campus administrators are more willing to put students' needs ahead of professors' wishes. About half of digital learning leaders and college presidents say saving money on textbooks justifies some loss of faculty control. (Provosts are divided.)

Advocates for students and for open educational resources said they appreciate the faculty support for OER but challenge the assertion that free or inexpensive textbook alternatives are of lesser quality.

David Wiley, chief learning officer of Lumen Learning and a leader in the OER movement, said he was struck that nearly three-quarters of faculty members expressed support for OER, since last year's Babson survey, he said, found that "only 30 percent of faculty were either very aware or aware of OER."

But he said he was "disappointed" that the survey question equated "lower-cost materials with lower-quality materials," which he said reinforced "a common myth about OER … Multiple peer-reviewed studies demonstrate that students whose faculty adopt OER perform the same or better across a range of outcomes."

Wiley also said that the question about faculty control "missed an opportunity … I think a more interesting question would have asked the degree to which faculty find it either moral or ethical to adopt higher-cost learning materials when dramatically lower-cost materials of equal quality are available."

The downward pressure on the prices of course materials is hurting many publishers' bottom lines, and some of them are responding by embracing open resources (creating some suspicion among advocates).

Others are adopting their own approaches to lower-priced textbooks, often under the broad term of "inclusive access," platforms that make digital course content available to students on the first day of class at a discounted rate that is often included as part of tuition.

The survey asked respondents whether they believed publishers' inclusive-access programs were achieving their twin goals of lowering students' spending on course materials and improving educational outcomes by making sure students have access to materials at the start of the term.

A plurality (40 percent) said they believed the programs achieve both goals, while 31 percent said the programs were only reducing costs and 6 percent said they were only improving accessibility.

A quarter, 23 percent, said they were doing neither.

"The results on textbook costs show the inherent tension in a system where those who select the textbook (faculty) do not pay for it," said Seaman, of the Babson research group. "Faculty acknowledge that the costs are too high, that something (probably OER) should be done about it, just as long as I still get to pick whatever book I want for my course."

Nicole Allen, director of open education at SPARC, an advocacy group, said that "the textbook affordability conversation cannot just be about cost. It would be a mistake to replace the current, broken system with inclusive access or another lower-priced version of the same old thing -- we've already seen how that story ends. Institutions should be prioritizing support for models like OER that enhance rather than limit academic freedom, and allow quality and affordability to go hand in hand."

Other Findings

The survey explored numerous other topics. Among them:

Assessment. As public and political pressure builds on colleges to provide evidence about their performance and value, one of the major ways of doing so -- various approaches to measuring student learning -- continues to be viewed with suspicion and disdain by many professors.

Survey respondents were more likely to disagree than agree that assessment efforts on their campuses have "improved the quality of teaching and learning" (38 percent disagree versus 25 percent agree) or "helped increase degree completion rates" (36 percent disagree versus 27 percent agree).

Part of their skepticism may lie in the fact that many professors don't feel that anything useful results from the efforts. Just a quarter of instructors (26 percent) say they regularly receive data gathered from their college's assessment efforts (52 percent say they don't), and 28 percent agree that "there is meaningful discussion at my college about how to use the assessment information." About a third, 34 percent, say they have used data from these assessments to improve their teaching.

The other problem for many faculty members stems from their qualms about the motivations for assessment. Nearly six in 10 respondents (59 percent) agree that assessment efforts "seem primarily focused on satisfying outside groups such as accreditors or politicians," rather than serving students.

Online program management companies. Scores of colleges have turned to outside providers, known as OPMs, to create, expand or manage their online academic programs. Nearly four in 10 faculty members (39 percent) believe colleges should not work with outside companies in this way, but a majority, 58 percent, say that institutions should hire such providers to help them "with particular areas in which they do not have the in-house expertise."

The faculty members' views are largely in line with the digital learning leaders, 61 percent of whom say colleges should use OPMs selectively.

Accessibility. Many more colleges are paying attention to the extent to which their digital offerings are accessible to people with disabilities. More than two-thirds of instructors (69 percent) said their institution offers training on how to make course materials compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act. And between 60 and 70 percent of instructors say the courses they teach offer screen-reader capability (66 percent), provide alternative text to visual elements (64 percent) and make links descriptive for people with visual disabilities and caption video and transcribe audio (61 percent each).

Digital courseware. One-third of instructors said their courses use digital courseware -- software that delivers instructional content that can typically be customized to courses and adapted to work across different types of institutions and learning environments. Of those who answered that way, 71 percent said the courseware has adaptive or personalized learning tools or functionality.

Nearly two-thirds of those instructors (63 percent) said they are involved in selecting the digital courseware for their courses, and about a quarter (26 percent) said their college or university has a formalized process for evaluating digital courseware.