Free Download

Last year Inside Higher Ed's Survey of College and University Business Officers found four-year private college officials to be increasingly concerned about the viability of their institutions -- and more worried than their peers at other institutions.

A year later, CBOs at private four-years, perhaps surprisingly, appear somewhat more optimistic. But their peers at four-year public colleges -- especially those that aren't flagship or major research universities -- feel the screws tightening.

Inside Higher Ed's 2019 version of the survey, released today in advance of the annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers, suggests that CBOs at regional public colleges -- which a recently published Inside Higher Ed special report calls the "vast middle" of public higher education, positioned between research universities and community colleges -- are more pessimistic than their peers on multiple fronts.

They are less confident in the financial stability of their institutions over a decade than their counterparts in any other sector (28 percent express confidence, none strongly, compared to an average for all institutions of 50 percent); more likely than those at other types of colleges to expect their institution to share academic programs or administrative functions with another college in the next five years, and to say their institution should share administrative functions or merge in that time; and less likely to believe their colleges are well prepared to withstand the economic downturn that many economists predict is on the way.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2019 Survey of College and University Business Officers was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Tuesday, Inside Higher Ed’s Doug Lederman and business officers from the College of Lake County and the Universities of Memphis and New England will discuss the survey at the annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers. More information on that session can be found here.

On Tuesday, Aug. 6, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed editors will analyze the survey’s findings and answer readers’ questions in a free webcast. To register, please click here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of business officers was made possible in part by support from EY-Parthenon, Jenzabar, Laserfiche, Oracle and TouchNet.

The other institutions that acknowledge more vulnerability are not distinguished by their sector, but by their location.

Chief business officers from colleges in the Northeast are significantly less likely than their peers elsewhere to express confidence in their institutions' financial stability over 10 years (38 percent versus the overall average of 50 percent), and they are more likely to have had internal discussions about a merger (19 percent versus a national average of 13 percent) and to believe their institution should merge (28 percent versus 16 percent or lower for other regions) or share administrative functions with another college (77 percent versus 65 percent or lower).

Colleges and universities in the Midwest see themselves as somewhat less vulnerable than their Northeast counterparts but are generally less bullish than CBOs in the South and West.

Those are among the overarching findings of this year's survey, conducted in conjunction with Gallup. Business leaders from 418 public and private nonprofit colleges responded to the survey, which also produced other compelling results:

- Thirty percent of private nonprofit institutions (and nearly half of private baccalaureate colleges) took funds from their endowment over and above their normal distribution policies -- often a sign of financial distress.

- Chief business officers are not overly confident in their institutions' ability to change course quickly, as some experts on higher education suggest may be increasingly necessary in this time of fast-paced technological change and shifting economic conditions. Only slightly more CBOs agree than disagree (38 percent versus 30 percent) that their college has "the right mind-set to respond quickly to needed changes," and that they have "the right tools and processes" to adapt quickly (35 percent versus 29 percent).

- Business officers are likelier to agree than to disagree that the American economy will suffer a significant downturn in the next 18 months, to worry about the impact of a downturn on their institutions and to believe their college or university is better prepared to handle a downturn than it was during the Great Recession a decade ago.

The Financial Picture

Inside Higher Ed's 2019 survey went into the field this spring at a time of mixed economic news. The overall U.S. economy continues to strengthen, and that has led to some fairly positive trends in state appropriations for public higher education institutions. Federal spending on financial aid rose again last year, and House Democrats are pushing more big increases.

But the overarching demographic and financial trends that are roiling the country -- especially in the Northeast and Midwest -- continue to take their toll on small, less wealthy and rural colleges, with several private institutions closing in the first half of 2019.

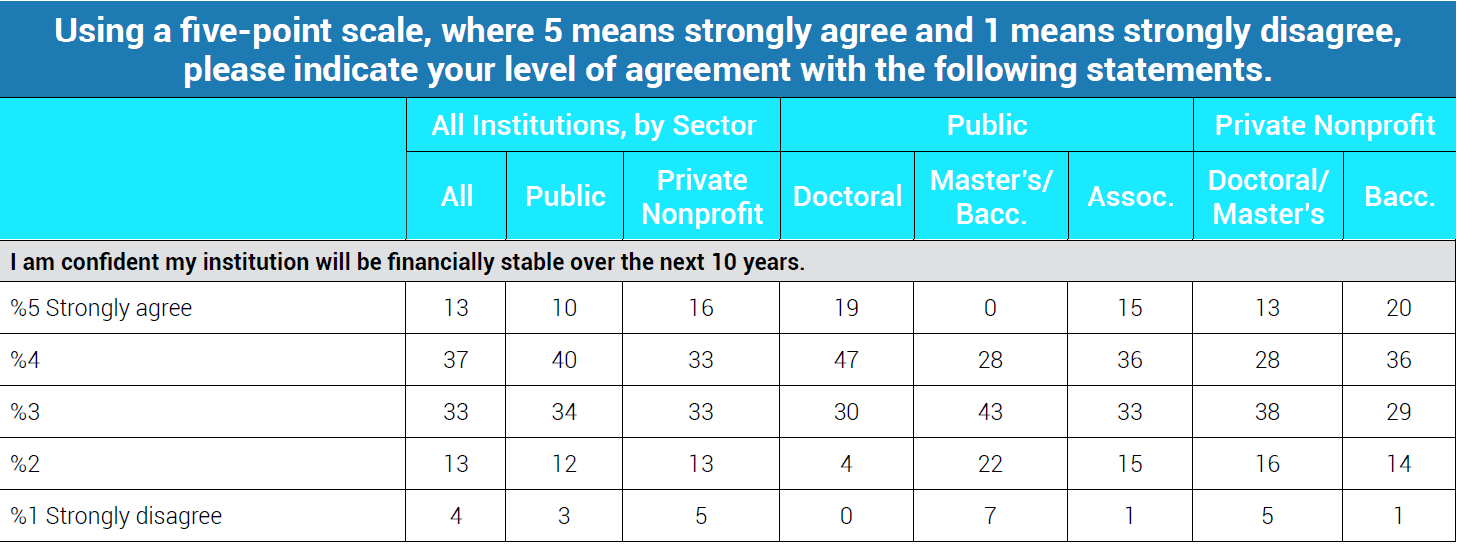

Viewed collectively, college chief financial officers are slightly more optimistic this year than they have been. Their overall answers to Inside Higher Ed's equivalent of a consumer confidence survey -- an annual question about how confident business officers are in the five- and 10-year financial stability of their institutions -- are basically flat from last year, with 50 percent of public and 49 percent of private nonprofit business officers strongly agreeing or agreeing that their institution "will be financially stable over the next 10 years."

But those averages mask major differences by sector. Two-thirds of public doctoral university CBOs agreed they were confident, as did 56 percent of private baccalaureate business officers (up sharply from 44 percent in 2018) and 51 percent of community college financial officers. But only 28 percent of chief financial officers at public master's and baccalaureate institutions agreed, as did 41 percent of those at private doctoral and master's universities.

That was one of several realms in which financial officials at nondoctoral four-year public universities offered a more pessimistic take on their financial situations.

The survey asked business officers a series of questions about mergers and other forms of consolidation or collaboration.

Fewer CBOs this year (12 percent) than last year (17 percent) said senior administrators at their college or university had "serious internal discussions" in the last year about merging with another college; roughly the same (28 percent this year versus 27 percent last year) said such discussions had occurred about consolidating programs or operations with another institution.

They are generally skeptical that their institutions will themselves merge, with only 6 percent of CBOs saying their institution is very or somewhat likely to merge into or be acquired by another college or university within five years. (Somewhat more business officers, 14 percent, say their institution is likely to be on the acquiring side in a merger or consolidation.)

But more CBOs, 43 percent, say their institutions are very or somewhat likely to share administrative functions or to combine academic programs with another college or university in the next five years. Those numbers are both up meaningfully from 2018, when 37 percent of business officers said their institutions were likely to share administrative functions within three years and 30 percent expected their college or university to combine academic programs with another institution during that time frame.

When asked if their institution should merge or consolidate operations, the answers were higher across the board. Eighteen percent of business officers said their college should merge with another, 62 percent said they should share administrative functions and 66 percent said they should combine academic programs. The merger number is flat from last year's survey, but in 2018 only 50 percent of CBOs said their institution should share administrative functions and 53 percent said they should combine academic programs.

Asked broadly about the possibility of closures or mergers, roughly a third of business officers predicted that more than 10 colleges will close in the 2019-20 fiscal year, a third said there would be six to 10, and a third predicted five or fewer.

A plurality of CBOs (45 percent) said they expected at least six private college mergers in the coming year, of whom 15 percent predicted more than 10. Far fewer (19 percent) envisioned at least six public college mergers, probably recognizing the significant political impediments that make such mergers much harder than combinations of private colleges (which are hard enough).

Reflecting the shift mentioned at the start of this article, private nonprofit college business officers were significantly less likely this year than they were in 2018 to say senior administrators at their institution had discussed a merger, at 12 percent versus 23 percent last year. CBOs at private baccalaureate institutions showed an even bigger drop, to 1 percent from 24 percent last year.

Exactly why private baccalaureate colleges seem to have had such a turnaround on this and a handful of other financial indicators -- they are also likelier than they were in 2018 to express confidence in their institutions' financial stability over a decade (56 percent versus 44 percent) and far less inclined to predict that their college would merge with another (5 percent versus 14 percent) -- is hard to say. The national economic outlook doesn't appear to have improved enough to justify such a shift; it is possible, of course, that the scores of private baccalaureate CBOs who responded to this year's survey represent a different and more optimistic group than were surveyed last year.

If the private nonprofit CBOs have a rosier view, business officers from nondoctoral four-year public universities see a worsening picture. Respondents from public master's and baccalaureate institutions were most likely to say they should merge (29 percent) or combine academic programs (77 percent).

Those officials were also more likely to predict there would be significant numbers of public college mergers (33 percent say at least six, compared to the all-institution average of 19 percent). As discussed below, they also are more worried about the effects of a possible recession and less confident in their institutions' ability to adapt quickly to a changing environment.

It's no clearer why the four-year public CBOs are increasingly pessimistic than it is why their peers at four-year private colleges seem more optimistic; conditions don't appear to have changed drastically in a year.

But perhaps more of them are adopting the view expressed by Daniel Greenstein, chancellor of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, in Inside Higher Ed's new report on the state of regional public colleges. Discussing the danger of "inaction" in response to escalating financial and demographic pressures, Greenstein said, "Let's give it a name. It's called terminal financial decline. Let's give it a duration. It's got about seven to 10 years. Every choice we make has a consequence."

Another Recession?

Hanging over the economic picture in higher education and the country is the possibility -- which many economists say is a likelihood -- of a major downturn in the next year or so.

Nearly three in five CBOs (59 percent) strongly agree or agree they are worried about the impact an economic downturn could have on their institution; 17 percent disagree. (Community college business officers express the least concern, 47 percent, probably because they know adults and other working students tend to return to college when the job market worsens. Private baccalaureate institution CBOs are most worried, at 75 percent.)

Business officers may be worried about a recession because they believe "additional and significant spending cuts" would hurt their institution's quality. More CBOs disagree (42 percent) than agree (31 percent) that their college can make meaningful cuts without impairing quality. Once again, business officers at nondoctoral four-year public institutions feel most strongly that budget cuts would be damaging, with 62 percent disagreeing with the statement, up from 52 percent in 2018.

Over all, though, a larger proportion of business officers seem to believe their institution can make cuts without impairing quality, as seen in the chart below. That is unlikely to be a perspective shared by most faculty members.

More business officers agree (55 percent) than disagree (17 percent) that their colleges and universities are "better prepared" to deal with another downturn than they were with the 2008 recession. Once again, business officers at nondoctoral four-year public colleges are least confident: 35 percent agree their institutions are better prepared for the next recession.

Culture and Financial Understanding

How institutions respond to the continuing (and sometimes escalating) financial and demographic pressures on them can be the difference between thriving and surviving. The survey included new questions this year on how well positioned business officers believe their institutions are to adapt to a fast-changing environment. The answers were mixed.

Thirty-eight percent of all CBOs agreed or strongly agreed (9 percent) that "at my college, we have the right mind-set to respond quickly to needed changes," while 30 percent disagreed and 32 percent were neutral. Business officers at comprehensive and baccalaureate public institutions were least confident, with 32 percent agreeing and 39 percent disagreeing. Private doctoral and master's CBOs were most confident, at 44 percent.

Business officers were similarly divided on whether their institutions have the "right tools and processes to respond quickly to needed changes," with 35 percent agreeing and 29 percent disagreeing. On this question, business officers at public doctoral institutions had the bleakest view: just 20 percent agreed (none strongly) and 43 percent disagreed.

“It is refreshing (or encouraging) to see that about 40 percent of both public and private institutions agree or strongly agree that their institutions have the right mind-set (are willing and ready) to respond quickly to needed change," said Kasia Lundy, a partner/principal at EY-Parthenon, which consults with colleges on financial and other matters. "But higher ed has a long history and legacy, and relatively few institutions -- whether you consider absolute numbers or percentages -- ‘go out of business.’

"It is not at all clear today that higher ed stakeholders agree that change is needed or what purpose it aims to accomplish. Higher ed needs leaders with tremendous fortitude, and leaders need a ‘burning platform,’ to implement real change, in view of the impediments identified in the survey. But if today’s pressures are not enough, what will constitute this burning platform?”

Business officers continue to feel that they do not have the best data and other information with which to make decisions -- though the numbers are improving. Asked to respond to the statement "My institution has the data and other information it needs to make informed decisions about" a variety of key judgments, 54 percent agreed they had what they need to decide which academic programs to eliminate or enhance, and 52 percent said the same about assessing the efficacy of specific academic programs and majors.

That was the first time since Inside Higher Ed began asking this question in 2014 that an answer exceeded 50 percent. Responses on other questions lagged -- 46 percent responded positively on the performance of administrative technology, 41 percent on the performance of academic technology and 39 percent on the performance of administrative units -- but all of those numbers were higher than they were last year.

Cole Clark, managing director for higher education at Deloitte Services, said the finding that nearly half of CBOs believe their institution lacks the data to make informed decisions was "the most telling statistic of all from our perspective, given some of the other findings. "How will CBOs gauge the correct price point for tuition?" he said. "Understand which credentials programs are effective? Know what to quickly dial up, dial down, or discontinue?

Warning Sign on Endowments

Inside Higher Ed and Gallup asked an expanded set of questions about institutional endowments this year, and the questions elicited one of the most compelling findings of this year's report.

About seven in 10 business officers said endowment revenue provided at least some of their operating support, with the mean percentage being 4.9 percent -- 1.9 percent for public institutions and 8.8 percent for private colleges. The vast majority, 82 percent, said they expected their institution's endowment payout rate to remain where it has been over the next year.

But one in six CBOs -- and 30 percent of private nonprofit college financial officers and 47 percent of private baccalaureate officials -- acknowledged having taken funds from the endowment in the past 12 months "over and above levels called for under your normal spending policy, either through a loan or a special or supplemental distribution."

About half (51 percent) of those who said they had drawn additional funds last year said the amount was between $1 million and $5 million, while 39 percent said they had taken less than $1 million and 10 percent said they had drawn more than $5 million. Seventy percent of the business officers said they had taken total draws over the previous five years of less than $5 million, while 25 percent said they had drawn between $5 million and $30 million over that time, and 5 percent said they had taken out more than $30 million.

Sixteen percent of all institutions with endowments said they anticipated drawing down extra funds from their endowments in the next 12 months, roughly comparable to the proportion who said they had done so in the previous 12 months.

Those answers troubled some of the financial experts who looked over the survey report.

"This is a remarkable sign of diminishing competitiveness, excess of expenses compared to revenue, or both," Stefano Falconi, a managing director at Berkeley Research Group, said via email. "Either way, it is an early warning that the institution is not financially feasible and is forced to dip into the endowment corpus in order to survive. This is clearly not sustainable, since those reserves will sooner or later be depleted. In other words, this is a clear sign that the institution is departing from financial equilibrium."

Financial Reporting and Transparency

The survey asked numerous questions about how institutional leaders measured their financial health and informed campus constituents about the situation.

The proportion of CBOs saying they ran financial reports that include projections to year end rose slightly this year, to 93 percent from 91 percent, though the percentage who said they ran the reports weekly or monthly dropped, to 65 percent from 72 percent in 2018.

Fewer business officers said the financial reports were distributed to governing board members (to 65 percent from 69 percent in 2018) and faculty governing bodies (to 8 percent from 12 percent last year).

The CBOs expressed decreasing confidence in the importance of financial transparency and the financial understanding of key campus constituents. Last year 62 percent of business officers agreed that "greater transparency in campus decision making will result in better financial decisions"; that figure fell to 55 percent in this year's survey, a drop driven by a decline from 34 percent to 25 percent for public college CBOs (and a 15-percentage-point drop among community college officers).

CBOs responding to Inside Higher Ed surveys have consistently responded that faculty members are least likely among major campus constituencies to be "aware of and understand the financial challenges" facing their institution, and this year just 32 percent agreed that faculty members understand the financial picture, down from 44 percent in 2018.

But business officers also judged trustees more harshly this year: just 35 percent "strongly agreed" that board members understand the financial challenges facing the institution, down from 44 percent last year (the proportion agreeing or strongly agreeing stayed constant, at 78 percent, though).

The proportion strongly agreeing or agreeing that senior administrators "get it," by contrast, rose to 90 percent from 80 percent in 2018, driven by a sharp rise among community college CBOs.

Other Topics

The survey covered a wide range of additional issues, including the following:

Alternative revenue sources. Another new question in this year's survey asked business officers to assess the promise of a range of possible approaches for producing more revenue for their institutions, as their traditional sources (state funding and tuition) tighten. The leading choice for CBOs over all, and in almost every sector, was alternative credentials (certificates, noncredit certifications, etc.), which 70 percent of all financial officers favored.

Creating new programs for new audiences, such as senior citizens, was next at 49 percent, followed by expanded use of facilities (rental to other groups, weekend use) at 43 percent and outsourcing of units that are traditional core operations (such as parking or student housing) at 19 percent.

Deloitte's Clark said he wondered "if institutions will be able to capitalize" on the alternative credentials opportunity many of them see. "Can 'traditional' systems and norms adapt to accommodate students who consume courses (and, employers who demand skills) in a dramatically different manner? From our experience, many institutions simply don’t have flexibility in their enterprise systems or their cultures to adapt to the changes these kinds of programs will demand, especially in order to make them 'mainstream.' "

Discount rates. Business officers divide evenly as to whether their college’s current tuition discount rate is unsustainable -- 38 percent agree it is, and 37 percent disagree. Also, after 48 percent of CBOs strongly agreed or agreed their college’s tuition discount rate was unsustainable in the 2018 survey, the percentage has reverted to 38 percent, similar to where it was in 2016 and 2017.

Tuition resets. Private colleges, particularly, went through a couple of waves of "tuition resets" in the last two years, but the approach may not become a tsunami. Only 7 percent of CBOs said they had lowered their published tuition rate, while another 23 percent said they have "considered doing so."

The vast majority, 71 percent, said they had not considered such a reset. Almost three-quarters of those who had not reset their tuition said they did not believe it would benefit the institution at all; just 3 percent said they believed it would help the institution "a lot."

Debt. Most CBOs (75 percent) continue to believe that their institution has an appropriate amount of debt; the figure was 77 percent in 2018. This is another area where the worry of nondoctoral public four-year institution CBOs reveals itself: almost a quarter of them, 23 percent, say their institution has too much debt, up from 12 percent in 2018.