You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

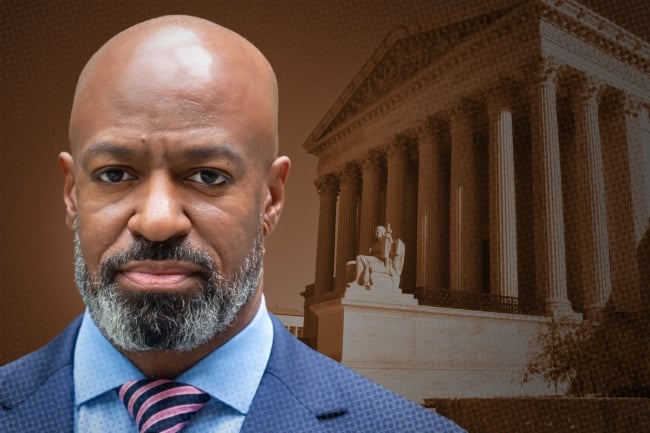

Bryan Cook, higher ed policy director at the Urban Institute, has been tracking the impact of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ruling for the past year.

Photo Illustration by Justin Morrison | Urban Institute | Getty Images

Saturday marked one year since the Supreme Court struck down race-conscious admissions in the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill ruling.

The decision has had an undeniable impact on colleges’ admissions strategies and policies. Many institutions changed their application essay prompts, some to provide space for students to reflect on their identities, others to avoid legal scrutiny. Some colleges are ramping up their financial aid initiatives as a race-neutral alternative to maintain diversity. The ruling even reignited national debates over other equity issues like legacy preferences and standardized test requirements.

Unanswered legal questions from the vague, at times self-contradictory, ruling also remain. Does it apply to bridge programs for Black and Latino students? Are scholarships for ethnic minorities against the law? SCOTUS has yet to take up any cases that would clarify these issues, and the answers from colleges and state lawmakers vary wildly.

But even as SFFA’s tremors shake up admissions and financial aid policies, the impact of the ruling on the demographics of selective colleges has been harder to ascertain.

Bryan Cook, director of higher education policy at the Urban Institute, has been tracking the effects of the court’s decision for a year now—or, at least, he’s been trying to.

“Collecting and analyzing the data for this year and next year is going to be critical to having any sense of what the future of equitable admissions looks like,” he said.

Cook spoke with Inside Higher Ed about his project and how that future is shaping up. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You’ve been tracking the effects of the affirmative action ban on higher ed for a year now. What have you found?

A: It’s a bit of a challenge in terms of tracking the effects, because there are a number of moving parts. We started to see some preliminary findings from the Common App that gave some indication that they’re not seeing much change in terms of the demographic profile of applicants to selective institutions, number of applicants, where they’re applying, et cetera. All of that seems similar to what they’ve seen in prior years.

Then comes the admissions process, and there are a couple issues with that. First of all, there is no publicly available admissions data; that doesn’t exist in IPEDS [the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System], at least in terms of disaggregation by race. They only separate by gender. The admit piece is also being confounded as it pertains to the Supreme Court decision because of all the issues with the FAFSA rollout, which makes teasing out any specific impact of the Supreme Court decision very difficult. There’s no good year for FAFSA issues, but coming on the heels of the Supreme Court decision eliminating or severely restricting the use of race in the admissions process was particularly bad.

Then, ultimately, there is the enrollment piece, which we won’t know until later in the fall. Those are the three pieces that we’re really trying to follow, but the applicant data is the only one that we’ve gotten any real sense of now. We’re in the process at Urban of launching a project to work with a set of schools to collect admit, applicant and enrollee data, and if we’re able to get enough schools to participate, there’s a good chance we’ll have some admit data to at least get a sense of whether there have been any changes this year relative to prior years.

Q: How is the ban changing institutions’ admissions practices?

A: When we were first talking to schools about our project of collecting applicant, admit and enrollment data, one of the things that was interesting is that there was more hesitancy to share information about admissions practices and policies than to share the actual data. Because while it is the data that may trigger potential lawsuits, it’s the actual admissions practices that, as we learned from the Supreme Court ruling, can get schools in trouble. So we haven’t seen any widespread research that really highlights that information.

But if you look at some of [the National Association for College Admission Counseling]’s prior research from their state of admissions survey that they used to do, I think there are a lot of schools that have been making modifications to their admissions policies and practices for the past couple of years, because everyone knew of the lawsuit and could guess the eventual ruling. So I think a lot of schools have been making modifications in the ramp-up to last year’s decision. We just don’t know tangibly what those look like. That might be why we haven’t seen a significant drop-off in the profile of applicants from the Common App data—not so much that applicants are unaware of the decision or don’t really feel it impacts them, but that a lot of schools have ramped up their efforts to encourage a more diverse applicant pool. But without some sort of large, in-depth study, the available national data aren’t going to give us any insight into diversity. We may eventually, at least with applicants and enrollees, get some numbers, but we’re not going to get down to the why without some more in-depth analysis and school participation.

Q: It sounds like researching the effects of this decision has been a real challenge.

A: It has, but this kind of research has always been difficult. Part of that is because for the federal IPEDS data, which is the most robust we have, the only disaggregation they provide is by gender. They do not provide it by race. Prior to the Supreme Court decision, that was an issue just for those doing research around the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in certain schools. One of the challenges was you couldn’t tell if that lack of diversity was a function of a school’s admissions policy or if it was just because they didn’t have a very diverse applicant pool; you had no real sense of that. There have been calls for a while to add racial breakdowns to the data set, but there’s always also pushback because of the additional burden to schools that now have to report another set of disaggregated data.

Fast-forward to the Supreme Court decision. Now everybody is clamoring for access to this data to understand potential impact, and it’s not there. My understanding is that a racial breakdown has now been submitted to [the Office of Management and Budget] to be part of the 2025–26 data collection, so it seems like we will have it going forward. But even once it’s added it won’t be retroactive, so it won’t tell us anything about the actual impact of the Supreme Court decision.

Q: Does that mean it will be hard to track the impact of the FAFSA debacle on diversity, too?

A: The FAFSA issue has all but wiped the Supreme Court decision off the front pages of most of the higher education trade publications, and deservedly so; it has a much broader impact.

The thing that concerns me is, while there was a lack of clarity over how the Supreme Court decision was ultimately going to affect students of color, with the confluence of the ruling and FAFSA, I don’t think there’s any question that we could see an unprecedented decline in applicants and admit among students of color from low-income populations, who disproportionately are the ones filing FAFSA. That really underscores the need to collect some data this year on that applicant, admit and enrollee profile.

I think next year we will start to get some sense of a separation from the FAFSA issue and look more at the Supreme Court ruling’s impact. But without collection of data this year, we’re not going to have a baseline to understand. We literally have no idea about the impact of two significant issues in the higher education landscape on the diversity of our applicant pools. And because we’ll only know the racial and ethnic data beginning in 2025–26 and onward, we will have no baseline for understanding whether or not those numbers are significantly below what we’ve historically had. So collecting and analyzing that data for this year and likely next year are going to be critical to have any sense of what the future of equitable admissions looks like.

Q: What are you seeing in terms of institutional responses to the ruling and changes to admissions policies? Are those easier to track, and are there any overarching trends?

A: Well, the tools available to institutions to try and ensure a diverse and equitable entering class are, to some extent, dependent on the state in which they exist. Given a lot of the attacks that we’ve seen around DEI efforts, as well as some states’ expanded interpretation of the ruling to include financial aid, that really can limit what schools are able to do. For example, there are some schools that have utilized fellowships and scholarships to try and encourage a more diverse applicant pool, but that’s only in states where that’s allowable. For a lot of schools, it’s been more minor and modest tweaks. And they’re not necessarily publicly known.

When you talk to people who have done a lot of research on college admissions, one of the constant concerns has been that the admissions process is largely a black box. This just made it even more of a challenge to get full transparency in the admissions process after affirmative action, because schools are very concerned about their approaches being scrutinized from a legal perspective. There’s just not a lot of disclosure about any of those changes.

Q: So the threat of litigation is making it hard to understand the full scope of the ruling’s impact. Do you think that might be an intentional strategy from the right?

A: I think right now higher education broadly is just being extremely cautious. You think about the Supreme Court decision and the concern about potential lawsuits, you think about the campus protests and a lot of scrutiny that campus leaders are under in terms of how those have been addressed—I think there’s just a general sensitivity around decisions being made on college campuses, so that certainly impacts, from a research perspective, our ability to get schools to be willing to share information that would help us better understand the impact of things like the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision.

Q: There are precedents for SFFA—statewide bans on affirmative action in California, Michigan and Texas, for instance—where the impact on diversity at the most selective public institutions was immediate and devastating. Is there reason to believe the outcome on a national level will be similar?

A: It’s difficult to have a sense of how much those state examples portend for what we can expect nationally. When the Supreme Court decision came down, much of what was published, including things that I wrote at Urban, certainly suggested that what we’ve seen at the state level could serve as a precedent. But the thing that is significantly different, particularly for places like California, was that Proposition 209 [the referendum that banned race-conscious admissions in California in 1996] not only made national news, but pretty much everyone in the state knew about it and its implications. It’s still not clear how much the Supreme Court decision was being followed by high school seniors and their parents. Certainly you would think that they were aware of it, but the extent to which it would ultimately change patterns of behavior is unclear.

The one early marker that we have is the Common App data, which would seem to suggest, based on schools that participated in Common App, that there doesn’t seem to be that level of a shift. The thing to say about the Common App data is it’s essentially a sample. Because while it does have a large share of the selective college and university population as their members, it’s not clear what percentage of those schools’ applicants come through the Common App. We’re not sure whether the data represents 80 percent of applicants to those schools or 20 percent. It’s possible that in the end, it could very much look more like what we saw in California, with these significant drops in African American students or a shift in where they apply.

But we have to wait and see how this story plays out. If you were to think of it as a football game, we’re early in the first quarter. We’ve got a long way to go to figure out what the actual impact is going to be.