You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

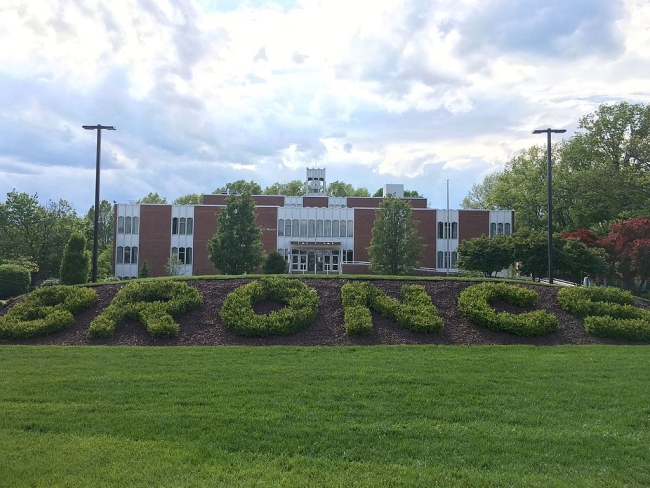

Rider University in Lawrenceville, N.J.

David Keddie/Wikimedia Commons

Analysts at Moody’s Investors Service recently downgraded Rider University’s bond rating, signaling that the credit rating agency is increasingly concerned about the institution's precarious finances.

Rider’s rating fell from Ba1 -- already a non-investment-grade or “junk” bond rating -- to Ba2 earlier this month. Such ratings indicate to potential investors that investing in the university is risky because the university may be unable to pay back its debts.

“The rating downgrade to Ba2 from Ba1 reflects Rider University’s continued very weak operating performance, reliance on a line of credit and recent increase in leverage, largely for working capital needs,” Moody's analysts wrote. “While the university has articulated strategies to improve operations, a turnaround, if achievable, will take multiple years.”

Rider, a private university in Lawrenceville, N.J., has been squeezed by the same financial headaches that plague many private colleges and universities -- namely falling enrollment, declining tuition and auxiliary revenue, and increasing debt.

"It’s widely known that the landscape of higher education is changing rapidly. The global pandemic has only exacerbated the existing challenges institutions like Rider have been facing, while also creating unforeseen new ones," Kristine Brown, a spokesperson for the university, said in an email.

Expenses and revenue loss related to the COVID-19 pandemic have also put stress on the university's finances. Rider lost about $27 million in room and board and auxiliary revenue over the past two fiscal years and spent $2 million in COVID-19 related costs last year, Brown said.

Rider’s enrollment has also declined considerably over the past decade, falling from a peak of 4,588 undergraduates in the 2009-10 academic year to 3,693 during the 2018-19 academic year, National Center for Education Statistics data showed. What's more, net tuition revenue fell by 8 percent between fiscal year 2016 and fiscal year 2020, according to Moody’s.

In an attempt to attract more students and lower its discount rate -- which is the percentage of the full tuition price that is subsidized through institutional financial aid -- Rider officials cut tuition by more than $10,000 starting this fall. Tuition for the 2021-22 academic year will cost $35,000. University officials hope the new sticker price will draw families who would have otherwise ruled out Rider.

“The initiative changes Rider’s high tuition, high discount pricing model, which creates a significant hurdle for students and families who believe the sticker price immediately puts a Rider education financially out of reach,” Brown said in a February statement.

While university leaders work to recruit and retain more students, continued financial challenges could work against them, said Michael Horn, co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, a nonprofit think tank. Students and parents have greater access to consumer information today than they did a decade ago, and Rider’s uncertain future could influence prospective students not to consider or attend Rider.

The university has relied more heavily on credit to fund operations in recent years, the Moody’s report showed. In fiscal year 2020, Rider reported $89 million in debt. That total jumped to $110 million after the university issued additional bonds in fiscal 2021. The university has budgeted debt repayment as part of normal operations, Brown said.

Moody’s recent downgrade will only make access to such credit more difficult, according to Horn.

“It’s going to make it harder for them to borrow at rates that are going to be attractive,” Horn said. “They’re basically covering expenses right now on a line of credit. So that’s going to increase future costs for the foreseeable future, which just puts a bigger and bigger toll on the institution.”

Brown said the university is planning on "trimming the budget" but that it is not planning layoffs at this time.

A few of the university’s attributes prevented Moody’s from lowering Rider’s credit rating even further. The university brought in $130 million in revenue during fiscal year 2020, and the main Lawrenceville campus was recently appraised at $230 million, which is “well in excess of outstanding debt,” analysts wrote.

Moody’s also praised university officials' efforts to turn things around.

“Management’s commitment to improve financial performance in the face of softened revenue growth prospects is a credit strength,” the report states. “The university faces multiple constraints to doing so, including a less flexible labor environment and litigation surrounding the sale of its Westminster property in Princeton, New Jersey. The university has also articulated plans to strengthen its brand and pricing power, although success is uncertain in a highly competitive and evolving market environment.”

University officials have taken several steps to attract more students in recent years.

"We have focused on affordability and a vibrant living learning environment, one that fully engages students inside and outside the classroom. We’ve invested heavily in our campus facilities, new program development and course delivery platforms, while also implementing strategic operational efficiencies and cost reductions," Brown said.

Greater enrollment, increased net tuition and auxiliary revenue and improved operating margins could prompt Moody’s to upgrade the university’s rating, the report said. On the other hand, Rider could face another downgrade if its operating deficits worsen or its material debt increases without a compensating increase in flexible reserves.

Rider has a few options to improve its financial picture, Horn said. The first is a declaration of financial exigency, which would allow the university to abandon its debt obligations and restructure the institution from the ground up. It would also give them room to lay off tenured and nontenured faculty. The university's faculty union is asking the institution to guarantee not to lay off any faculty members as part of its next contract, but financial exigency would bypass this potential agreement.

“That would be a pretty big, bold move,” Horn said. “But it would be one to try to save the institution.”

The university could also follow the path of Southern New Hampshire University, which quickly pivoted to focus on online and continuing education in the early 2000s after the recession increased financial pressure on the private university. Partnering with an online program management company or other third-party could provide Rider access to additional capital, Horn said. Rider could also search for a merger or acquisition partner, as many struggling institutions have done.

The last -- and potentially most difficult -- option would be for university administrators to make incremental improvements to slowly get the institution into better financial shape.

“Try to attract people to the institution. Show that there is an attractive set of value propositions around Rider. Maybe they create partnerships with employers and do something novel around employment guarantees or something new,” Horn said. “Show some confidence for the students that the institution will be there."