You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

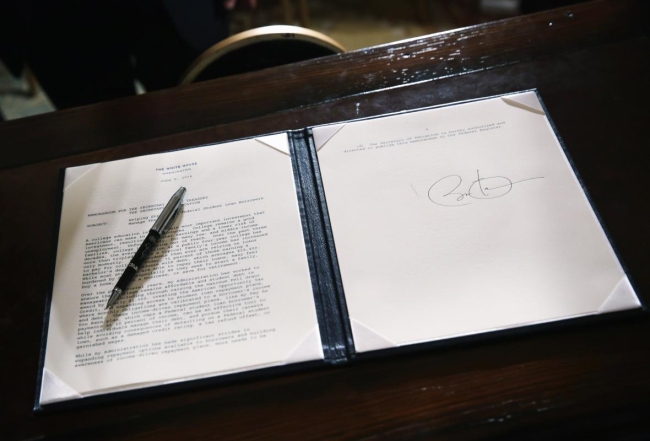

President Barack Obama signed a memorandum on reducing student loan debt in 2014. A new estimate tries to pinpoint how much student lending could cost the government, not borrowers.

Alex Wong/Staff via Getty Images

It is an eye-popping number: $435 billion.

That is the amount of money the federal government can expect to lose on its $1.37 trillion student loan portfolio, according to an analysis consultants performed for the Department of Education. That analysis anticipates borrowers paying back $935 billion in principal and interest on their student loans, leaving $435 billion for taxpayers to absorb.

So what, exactly, does $435 billion represent? The Wall Street Journal, which recently uncovered and reported on the student loan analysis, compared it to the $535 billion private lenders lost on subprime mortgages in the 2008 financial crisis.

Count the $435 billion in other ways, though, and it comes to represent many, many different things about the patchwork way this country pays for students to attend colleges and universities -- and the debate unfolding about whether that patchwork is going to change substantially in the near future.

This dollar amount can be a rallying cry for critics who say the current student loan system channels public money to colleges who provide little spending accountability and take on little risk in return. It can be largely irrelevant for those who want to reform the system but believe it still fulfills its purpose of providing educational opportunity to students from all walks of life who otherwise might not be able to afford a college education. Or it can be a number that means nothing without context in a loan system that shouldn’t necessarily turn a profit for the government.

No matter what, the number certainly grabs attention. And it has some potential to influence the long-simmering debate over student loan debt, a debate that after this fall's election has inched toward President-elect Joe Biden’s plans to cancel $10,000 in student debt per borrower and eliminate tuition for many students at public colleges and historically Black institutions.

It's important to note a few disclaimers about this $435 billion figure before proceeding any further. The estimated loss comes from modeling developed by FI Consulting for the Department of Education and checked by the accounting firm Deloitte. They reportedly looked at the amount of student loans the government held at the beginning of this year, but they didn’t include loans from private lenders.

Inside Higher Ed requested a copy of the consultant’s report from the Department of Education. A spokesperson acknowledged the request but had yet to provide a copy as of Tuesday.

That leaves some of the details murky. The analysis appears to be accounting for losses over the life of the loans in the federal government’s portfolio -- a life span that can stretch for multiple decades, meaning losses wouldn’t be realized at once. But key underlying financial assumptions are unclear. Different assumptions could drive up or down the expected cost to the government.

What is clear based on available details is that income-based repayment programs were major contributors to the projected losses. Students enrolled in income-based repayment programs only pay a percentage of their discretionary income toward their loans. The government forgives loans for those that haven’t paid back their entire balances after a period of time -- 10, 20 or 25 years, depending on particulars.

The Department of Education’s consultants estimated that borrowers in income-driven repayment plans will repay 51 percent of their balances on average, according to the Journal. Borrowers in other repayment plans will repay 80 percent.

These details aren’t surprising to some of those who’ve been following the particulars of the federal student loan portfolio.

Earlier this year, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office examined federal student loans expected to be disbursed between 2020 and 2029. The feds can expect to forgive $40 billion of undergraduate student debt issued during this period, the CBO found. They can anticipate forgiving $167 billion of student loans given to graduate borrowers.

The amount of dollars being repaid through income-driven plans rose drastically over the last decade, according to the CBO. In 2010, about 12 percent of federal loan volume was being repaid through income-driven plans. By 2017, the amount had skyrocketed to 45 percent.

Those repaying through income-driven plans don’t default on their loans as frequently as others, the CBO found. But the government loses 17 cents for every dollar that goes into an income-driven plan.

How do the projections the consultants put together for the Department of Education stack up to the CBO report? They’re close enough, according to many experts.

“I wouldn’t put a lot of stock in the exact number, because there are so many parameters they’re estimating,” said Beth Akers, a senior fellow who specializes in higher education economics at the Manhattan Institute, a free-market think tank. “The real point is this thing is operating at a loss.”

But is a loss a problem?

“We’ve designed federal student lending as a program rather than as any sort of lending marketplace,” Akers said. “We’re charging well-below-market interest rates on something, then we add on these incredibly generous safety nets that allow people not to repay their loans under pretty generous circumstances.”

Daniel Madzelan, assistant vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education, which is the higher education sector’s most prominent lobbying group in Washington, D.C., put it another way.

“What it really is, is the result of a conscious public policy choice,” he said. “Now, we can move on from there and debate whether the public policy choice is the correct one today, but it’s still public policy.”

Some critics have argued that federal student loans are problematic because they are effectively not underwritten. An underwriting process could have lenders verifying income, assets, credit history or other factors to determine how likely it is that a student will be able to repay a loan. Lenders could then price loans to take different risk levels into account.

But defenders of the system retort that the lack of underwriting standards is by design. The government lends to students who might not be able to access loans on the private market -- or who would pay much higher interest rates to private lenders who consider them borrowers at higher risk of default and price their loans accordingly.

“It comes back to a conscious policy decision that it is important for people to have access to a higher education,” Madzelan said. “I don’t know what other kind of credit availability is out there in the world that looks like student loans. The federal government is willing to lend money to 18-year-olds with no credit history, no employment history, no cosigner, no collateral, and is thus willing to take a chance on that particular individual.”

Adding a wrinkle is the large number of dollars tied up in graduate loans. Federal lending programs don’t limit how much students in graduate school can borrow, while the government’s loans to undergraduates come with strict limits. As a result, critics argue, graduate students can disproportionately run up large debts, enroll in income-based repayment plans and eventually have their loans forgiven. Colleges and universities, critics add, have incentive to raise prices for graduate programs in order to take advantage of the federal government’s seemingly bottomless pockets, and they have few incentives to control their own costs.

Another federal lending program, the Parent PLUS program, also comes without annual or lifetime borrowing limits. It allows parents to borrow in order to finance their children’s undergraduate education. Reforming that program has been contentious. The Obama administration raised credit standards for Parent PLUS loans in 2011, which hit historically Black colleges and universities hard because the racial wealth gap limits Black families’ options for financing a college education. The administration went on to loosen standards for the program in 2014.

Might momentum mount to make changes to those lending programs? Observers from different ideological perspectives often seem to agree that something should be done, said Sandy Baum, nonresident senior fellow at the Urban Institute, a public policy think tank. But she doesn’t support the idea of leaving it up to the market to judge which students or families are most likely to repay their loans over time.

“The idea that we should stop lending to people who might not be good risks, let’s let the market deal with it and not worry about educational opportunity questions -- that I find objectionable,” she said. Even so, loans aren’t creating opportunity if they’re disproportionately saddling low-income parents with large amounts of debt, she said.

“It’s not a simple problem,” Baum said. “It’s definitely something that needs to be addressed. It’s a reasonable time to raise it.”

Remember, though, that many other policy options are floating around as the Biden administration prepares to take over come January. The idea of wiping out $10,000 in student debt from all borrowers is particularly fraught here because it can be argued that this exact same problem will resurface in the future without reforms to the lending programs themselves.

Or that $435 billion number might throw weight behind the idea that the federal government is already forgiving large amounts of debt for borrowers -- it’s just disproportionately benefiting those who go to graduate school and are sticking it out in income-driven repayment plans for a decade or two.

“Depending on what this analysis actually is, it does, to some degree, make the point that the government is already forgiving a fair amount of loans in a way that is targeted toward people with high debt burdens,” said Robert Shireman, director of higher education excellence and senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank. Shireman was also a deputy under secretary of education in the Obama administration.

“How that impacts the dynamics of the discussion around loan cancellation, I’m not sure,” he said.

Narrative often drives which policy ideas gain traction and which do not. That’s another reason this $435 billion number might matter if it breaks through into the popular narrative.

With the COVID-19 pandemic raging and economic turmoil unfolding across the country, it’s yet to be seen how close to the front of the stage higher education policy will land, said Frederick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

“Will education be seen as kind of central to this notion of how we get back to it as a society and make sure people aren’t getting left behind?” Hess said. “Or does education get seen as something that we’ve got to put on the back burner because there are more pressing priorities? I don’t know.”