You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

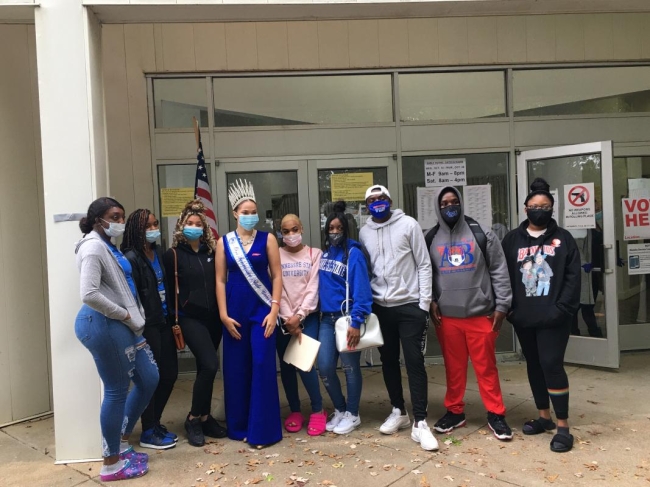

Several Tennessee State University students arrive to vote in Memphis after a three-hour bus ride from their Nashville campus.

La Toria Lane

In an already never-dealt-with-this-before kind of election, the New Hampshire Republican Party a couple of weeks ago threw another wrench into the obstacles facing college students who, according to polls, are particularly anxious to vote.

On top of questions coming up on campuses about an election being held during a global pandemic -- like how to vote next Tuesday if you’re a student confined in isolation -- the party appealed to the state’s Republican attorney general to not allow college students to vote if they’re being forced to live out of state because their campuses are closed.

“Students who do not live here and have no residence here at the time of the election are not qualified voters,” the party wrote the attorney general, Gordon MacDonald, bringing charges from the state’s Democratic Party of trying to suppress the vote of college students. According to polls by Harvard and Tufts Universities, college students are much more likely to vote for Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden than President Donald Trump.

To the applause of voting rights groups, the argument was rejected. But while the New Hampshire university system declined to comment on the dispute, a voting rights group called the Voter Protection Corps is worried the controversy has sowed more confusion in an already confusing election, particularly for those who have never voted before.

It is so concerned that it is taking out ads in the state, including one that has been emblazoned atop the online version of the University of New Hampshire’s student newspaper in recent days, saying, yes, university students might indeed be able to vote in the election, even if they are studying remotely.

Less than a week before the elections, voting groups and administrators at universities say they are not seeing widespread problems in students being able to cast their votes. And indeed, Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement said on Monday that five million 18- to 29-year-olds have already voted this year, and that in 13 battleground states, the number of those who have already voted about a week before the election exceeds the number who voted early in the 2016 election.

Still, myriad issues have been arising on campuses around the country, sending university administrators, voting groups and students scrambling. Many involve the complications of holding an election during a pandemic. A University of Michigan professor was dismayed to learn just 10 days ago that mail, including absentee ballots, was not being delivered to hundreds of students in quarantine or isolation. Trying to deal with its own students being kept away from other students, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee administration has hired a taxi company to take quarantined students who want to vote from their residence halls to a drive-by early polling station to fill out their ballots.

Long-standing laws in some states have also threatened to discourage college students from voting, leading a group of students at Tennessee State University, a historically Black university, last weekend to sleepily board a bus chartered by the college to take them on a three-hour trip from their campus in Nashville to vote in Memphis. At the University of Wisconsin at Superior, student interns are working to make sure other students know to bring their tuition bill if they want to vote because of a state law barring them from only using their student IDs.

At least one university, Bard College, in New York, has had to go to court to make it easier for its students to be able to vote. But civil rights groups have lost, or had delayed, at least two lawsuits that might have an impact on voting by students.

And in a year where there may be key razor-thin election margins, the potential that ballots cast by students will be disputed is so great that a national voting rights group, the Andrew Goodman Foundation, says it will be trying to keep track of every ballot cast by a college student that is thrown out for errors like neglecting to sign it. And then the group will try to contact the students to fix their ballots at their elections office. Another voting rights group, the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, says it will have monitors at the polls in 30 states.

A poll by Chegg.org and College Pulse released Tuesday found that 42 percent of 1,500 U.S. undergraduates surveyed said government officials or politicians are trying to suppress the student vote.

The good news, say groups like Generation Progress, the youth advocacy arm of the liberal Center for American Progress, as well as college administrators, is that haven't yet seen any widespread, obvious attempts to deter students from voting.

But as with the controversy in New Hampshire, there have been some disagreements locally.

Until last Friday, Jonathan Becker, executive vice president and vice president for academic affairs at Bard College, had been worried his students would be dissuaded from voting because they would have to go to a church that’s too small for people to socially distance in order to cast their ballot.

The liberal arts school has been fighting for decades with officials from surrounding Duchess County, which has been firmly Republican until recently becoming a swing area, over what it believed to be attempts to keep students from voting.

As recently as 2000, students at Bard and nearby Vassar College were barred from voting because they were not considered county residents. The New York State Supreme Court in 2009 had to order the county to not require that Bard students go to the extra trouble of filling out special ballots. In 2012, a federal court ordered that several Bard students be allowed to register to vote after the county’s election board rejected them. The students had been turned away because they filled in the street address of their dorm on the registration forms, but not the name of their dorm and their room number.

“From the moment I got to Bard, we’ve been involved in three lawsuits to try to assure students the right to vote,” said Becker, who is also director of Bard’s Center for Civic Engagement.

In the most recent fight, the college wanted the county to open a polling station on the campus. There’s no public transportation to the polling station at the Episcopal Church of St. John the Evangelist a mile and a half away, Becker said. And not only the college’s infectious disease expert but the church said it’s too small to safely handle voters during the pandemic.

But the county elections commissioner, Erik Haight, refused. “There is also a greater risk of a disruptive protest at a college campus than at a church,” he said in a deposition for a state Supreme Court suit filed by Bard and the Andrew Goodman Foundation to move the polling location onto campus. Haight in the deposition two weeks ago said it was too late to move the polling location anyway.

But when the county moved two other locations, the court ordered the polling location moved to campus.

Last Saturday at the Nashville campus of Tennessee State University, about 20 drowsy students stepped on a bus chartered by the university at 8 a.m., carrying photographs of John Lewis and other civil rights icons, to ride three hours to Memphis to vote.

The largest contingent of students at the university are from Memphis, said La Toria Lane, a Tennessee State graduate student in public administration, who led the effort to organize the trip.

Until recently, Tennessee had mandated that those registering to vote for the first time -- like college students -- could only cast their ballot in person. For students at the university from Memphis, the only way to vote was to make the three-hour trip.

Four years ago, Lane said, she’d tried to get an absentee ballot in the presidential election but was denied because it was her first time voting. She didn’t have a car, or the time, in between classes, to drive three hours to vote.

“I felt really discouraged. Like it was another way to really limit my vote,” she said. “It’s really hard to say we’re not voting when we’re not allowed to vote,” she said of young people.

A federal court last year did strike down the requirement. Under a new state law, first-time voters can vote by mail if they include a copy of their ID. But Tiara Thomas, a junior who has been leading voter registration efforts, said students were worried that delays in mail would mean their ballots wouldn’t arrive early enough to be voted. So they got on the bus.

Thomas, who is from Mississippi, was able to vote absentee by mail from Tennessee. But she ran into another law that voting rights groups say discourages students from voting. Mississippi is among seven states, according to the National Notary Association, that requires absentee ballots to be notarized.

Thomas worries that figuring out where to find a notary and pay for the service could discourage some college students voting for the first time from casting their ballot.

The NAACP, with legal support from several voting and civil rights groups, sued Missouri, which also requires absentee ballots to be notarized, to strike down its notary requirement. But that state’s Supreme Court upheld the law on Oct. 9.

It’s a worry even in Massachusetts, which has no requirement, said Jen McAndrew, director of communications, strategy and planning at Tufts’ Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life. The college has students from around the country, including some that require absentee votes sent back home to be notarized.

“The rules are so different from state to state,” she said. So as part of its program to encourage students to vote, the university is making notaries available. “These are the issues universities have to be thinking about,” she said.

“Imagine being a young person who doesn’t have that level of support,” she said.

Last month, a federal judge in Wisconsin delayed hearing a suit by Common Cause challenging a voter ID law until after the election.

That’s a problem for those who are from out of state and do not have a Wisconsin driver's license, a passport or another federal form of identification.

So the University of Wisconsin at Madison, trying to encourage voting, emailed upon request special student voting IDs that local elections officials said they would accept before the primary elections. The campus now has a website where students can download the IDs themselves, said campus spokeswoman Meredith McGlone.

But at the University of Wisconsin at Superior, its local elections officials are requiring students to bring to the polls either a state ID, or, for those from out of state, a student ID, and their most recent tuition bill showing they go to the university. Student interns at the university like Amber Heidenreich and Augusto Vladusic have been trying to spread the word.

An issue over IDs arose at the University of Alabama, when the system decided this summer to expand downloadable digital IDs that are taking the place of traditional cards.

Sam Reece, a senior in political science and American studies, thought that was great.

“But then I realized around the middle of July, Oh no, are we going to be able to use them to vote?”

He called the local elections office to see. They didn’t know and told him to check with the secretary of state. As an intern for the Andrew Goodman Foundation, he kept calling the state through the summer. Eventually, in September, when the foundation’s attorneys wrote, the state agreed to accept the digital IDs.

Reece is still nervous about what will happen on Election Day in a state where there is no early in-person voting at the polls, in a community that has different political views than the students. “Are we going to have poll workers who say, ‘I haven’t seen this kind of ID before’?”

And then there’s the global pandemic.

Jen Domagal-Goldman, executive director of the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, an effort by colleges nationally to encourage students to register and vote, said she’d worried about an outbreak sending students away from campuses during the voting. That, for the most part, hasn’t happened, she said.

But it’s still a concern, she said, as is the complexity of some states' laws.

Edie Goldberg, a political science professor and the lead faculty in the University of Michigan’s efforts to encourage student voting, said that when the campus set up quarantine and isolation dorms, it worked with Ann Arbor elections officials to place ballot drop-off boxes just outside the housing.

The surrounding county’s decision to impose a stay-at-home order does exempt going to vote.

But 10 days ago, she was talking to students in her online class who were in quarantine or isolation. And she heard they were not getting mail forwarded from their regular dorm rooms.

“It was a just-in-time discovery,” she said. “It’s not something that we had fully anticipated.” The university scrambled to get the ballots delivered.

The University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee had already contracted with a cab company to drive students being placed into quarantine or isolation residence hall units from their regular rooms, said Keri Duce, the campus’ external relations director. The drivers wear personal protective equipment, and the taxis are disinfected after every trip.

Milwaukee has set up curbside voting, where poll workers will come hand a ballot to voters, who fill them out in their vehicles, then hand them back. So the campus contracted with the cab company to take quarantined or isolated students from their rooms to the drive-up voting station outside the campus’s student union.

“It’s great -- the student never has to leave their Yellow Cab,” Duce said.

“The hurdles in a normal election cycle for first-time voters continue to exist, but this year it’s that much more complicated,” Domagal-Goldman said. “I’m not worried about college student apathy,” she said, “but how we are systemically creating obstacles.”