You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Health-care coverage for students could be at risk if the Affordable Care Act is repealed.

Istock.com/Ababsolutum

As Senate Republicans rush to confirm a conservative justice to the Supreme Court who could nudge it toward invalidating the Affordable Care Act, concerns are rising that an end to Obamacare could again leave millions of college students without health insurance.

“It’s almost unimaginable, the idea of students losing coverage in the middle of a pandemic,” said Erin Hemlin, director of health policy for the millennial advocacy group Young Invincibles.

Whether justices would really go that far, though, is hardly clear in a complicated legal battle that’s headed to the Supreme Court a week after the election. But Democrats have been arguing that the appointment of President Donald Trump’s nominee, former University of Notre Dame professor Amy Coney Barrett, would make it more likely.

Even so, experts in health care at colleges do not expect anything to change right away. The court is not expected to rule, in the case brought by several Republican state attorneys general asking for an outright repeal of the Affordable Care Act, until next summer.

Still, at least two studies this year have found that the law has cut the percentage of uninsured college students by half by allowing them to be on Medicaid or on their parents’ insurance. And the prospect of its loss is alarming some students, especially in the midst of a pandemic.

“It’s scary to think about it in the current situation,” said Kaylyn Goode, a 19-year-old George Washington University sophomore who gets insurance under a provision in the Affordable Care Act that requires parents’ employer health-care plans to cover dependents up to 26 years old.

“Even if we might not get as seriously ill” from coronavirus, “we don’t think we’re immune,” she said.

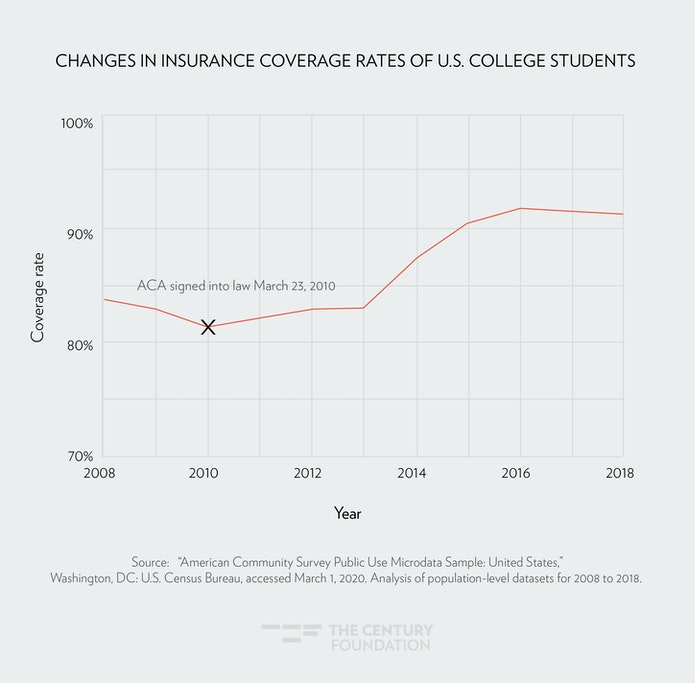

When the law was passed in 2010, about a fifth of college students were uninsured, according to separate studies by the Century Foundation and the Lookout Mountain Group, a nonprofit that studies health care in higher education.

But by 2018, that rate had dropped to 7.9 percent.

In all, the number of uninsured students nationally dropped over that time from 3.8 million to 1.5 million, according to the Lookout Mountain study.

“It would not be surprising to see the uninsured college student population increase to 15 percent or higher,” said Stephen Beckley, senior partner at HBC-SLBA, a health-care consulting company that works with colleges, and a co-founder of Lookout Mountain Group.

Both studies found that low-income, Black and Hispanic students in particular have been helped by the law.

Sixty-nine percent of Hispanic students had medical coverage in 2010, according to the Century Foundation. By 2018, that figure had risen to 85 percent.

Black students also saw an increase in coverage over that time, from 69 percent to 85 percent, the group’s study found.

Medicaid Expansion a Major Factor

The law’s biggest impact, according to both studies, is a provision that sent $69 billion in federal dollars last year to the 39 states that have chosen to expand Medicaid to about 12 million more people, including college students, who before had earned slightly too much to qualify for the health-care program.

The Century Foundation study found that the percentage of college students enrolled in Medicaid has increased from 59 percent in 2010 to 63 percent in 2020.

The Lookout Mountain study found that in the states that have expanded Medicaid, only 5.9 percent of students are uninsured. But in the states that did not expand Medicaid, twice as many, 11.6 percent of students, are not insured.

While 8.2 percent of Black students in states that have expanded the program are uninsured, the rate is 14.8 percent in states that have not, the study found.

The difference is even more stark among Hispanic students. Almost a quarter, 22.5 percent, do not have insurance in states that have not expanded Medicaid, compared to 9.8 percent in those that have, according to the Lookout Mountain study.

Though some states had already required insurers to keep covering dependents until they are 25 years old before the law’s passage, the Century Foundation study found that the percentage of students enrolled in employer plans increased from 59 percent to 63 percent between 2010 and 2018.

Jen Mishory, senior fellow at the Century Foundation and the study’s lead author, attributed the increase to more students being able to stay on their parents’ insurance.

“It used to be that our birthday gift when young adults turned 19 was to kick them off their parents’ insurance,” said Karen Pollitz, senior fellow at the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health-care policy think tank.

The foundation estimated in its annual survey of employers in 2011 that 2.3 million young adults were added to their parents' insurance in the health-care law’s first year.

Should the Affordable Care Act be entirely repealed, states could decide to dig into their coffers to make up for the loss of federal funds to continue covering the additional people through Medicaid.

However, that’s unlikely, Beckley said, at a time when many states are slashing spending, including for colleges, to fill the holes blown in their budgets by the coronavirus-caused recession.

A cautionary tale of how the end of expanded Medicaid could affect college students came last year when Brigham Young University announced it would no longer accept the low-income health program, leaving students with the option of buying private insurance or paying the $536-a-semester price for individuals to buy BYU’s health plan.

The university relented after a backlash. But before it did, Casey Wilson, who was just a few credits away from earning an art education degree and had just had a baby, told the Salt Lake Tribune she had to drop out.

“I am devastated,” Wilson told the newspaper, which described her as choking back tears as her baby cooed in her arms. “I love school. I want to graduate. But we’re a struggling family, and we don’t have the money for [private insurance].”

How Far Will the Court Go?

To some, like Doug Badger, a visiting fellow in domestic policy studies at the conservative Heritage Foundation, and a former adviser on health-care policy to President George W. Bush, students have nothing to worry about.

“The Court is not going to ‘repeal the law,’” he said in an email. “That almost certainly will not happen.”

He noted that lower court judges hearing the case have not gone along with the idea that the law should be thrown out. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit last year sent the case headed to the Supreme Court back to United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, where Judge Reed O’Connor was asked to reconsider his earlier ruling that the entire law should be thrown out.

MaryBeth Musumeci, associate director the Kaiser Family Foundation’s program on Medicaid and the uninsured, and a former Villanova University law professor who has been following the legal fight, said it’s impossible to predict what the court will decide.

A first step for the Supreme Court case will be whether it agrees with the Republican state attorneys general and lower courts that the penalty for violating the Affordable Care Act’s requirement to have insurance became unconstitutional when a Republican Congress changed the penalty for violating it to zero.

If so, the court would then have to decide if it agrees with the attorneys general and O’Connor that the entire law should be thrown out, or just parts of it.

Only Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito remain from the four who dissented in previous ACA cases upholding the law, saying they were in favor of eliminating the whole thing.

Where Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh, both appointed by Trump, stand is unknown, Musumeci said. Whether Barrett could then possibly be a fifth and deciding vote also isn’t known for sure, she said. But Barrett has criticized the court’s decision to not repeal the law, and her mentor, the late Antonin Scalia, had been among those who supported throwing out Obamacare.

The Trump administration has told the court it wants the mandate to have insurance declared unconstitutional but not all of the law should be thrown out. The administration hasn't said, though, which parts should be preserved.

Willian Thro, the University of Kentucky’s legal counsel, said that if parts of the law are repealed, those directly connected to the requirement to buy insurance, such as the mandate that the insurance cover pre-existing conditions, are most likely to be tossed. The parts expanding Medicaid or letting young adults be on their parents’ insurance are somewhat separate, he said.

Katie Keith, an adjunct Georgetown University Law Center professor who writes a blog focused on the Affordable Care Act for the policy journal Health Affairs, said it’s difficult to imagine that the court would invalidate a law that’s been around for 10 years. Still, she said, “it's hard to say because there are a range of potential outcomes. But I don't think anyone should underestimate the possibility that the law, or major parts of it, could be invalidated.”

College Plans Would Become Key

If the law were to be eliminated, the main option for students who lose coverage would be to buy insurance offered by their colleges, if it is available, Beckley said.

A repeal of Obamacare would also get rid of the subsidies that reduce the price for insurance on the Affordable Care Act marketplace. But because college plans insure younger people with fewer medical claims, the plans offer much cheaper premiums than those sold on the marketplace, said Devin Jopp, chief executive officer of the American College Health Association

While 90 percent of students go to colleges that offer insurance, according to a 2018 Lookout Mountain Group report, not all colleges offer coverage. An example is the California State University system.

But even if their college offers insurance, low-income students who have been able to get Medicaid would have a hard time paying the average $194-a-month premium for college plans, Jopp said.

Some public colleges might try to help low-income students pay the cost, but that will be “highly variable as many public colleges presently are under severe budget constraints,” Beckley said. “ Even privates may struggle.”

Students could also use financial aid or loans to pay for insurance, but students are already struggling to pay for living expenses beyond tuition. And they’re already weighed down by debt, Hemlin said.

“We saw this in the last couple of months, when students had to move off campus and didn’t even have laptops,” she said. Having to pay for insurance, or being hit with a large medical bill if they don’t have coverage, could force some students to drop out, she said.

Hemlin also worries that without the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that policies cover 10 essential benefits -- including doctor visits, hospital care and medication -- could mean a return to the skimpy plans colleges offered before the law.

Many colleges offered good plans before the law, Jopp said, but he acknowledged, “there were some dubious players in the marketplace, with $5,000 deductibles in some cases.”

In 2012, for instance, Inside Higher Ed reported the problems Arijit Guha, then a 30-year-old graduate student at Arizona State University, faced when he developed colon cancer. The cost of his treatment eclipsed $300,000, the lifetime maximum benefit on Arizona State’s Aetna plan. A provision in the Affordable Care Act that prohibits lifetime limits in insurance was being phased in and hadn’t taken effect at the time, and he was left without insurance.

Aetna, in response to the press coverage at the time, decided to cover his bills. (Guha died the following year, according to The Washington Post.)

However, any changes likely wouldn’t immediately take effect if the law were to be repealed. Federal funding to states to continue expanded Medicaid would stop. States, even if they could afford it, would have to ask the federal government for permission to cover those who make too much for regular Medicaid.

Even if the requirement to cover dependents older than 18 were to be repealed, individual insurers could decide to continue to let students stay on their parents’ plans. Pollitz said they would likely be able to stay on at least through the end of the plan year.