You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ISTOCK.COM/Nuthawut Somsuk

International students report adapting well to remote instruction at higher rates than their American peers, but they have concerns about staying safe and healthy and about navigating the health-care and immigration systems during the coronavirus pandemic, according to a new survey of 22,519 undergraduate students and 7,690 graduate and professional students at five public research universities conducted by the Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) Consortium.

“International students’ biggest concerns are not with academics, not with remote instruction, but rather with the larger environment -- health, safety and immigration,” said Igor Chirikov, the director of the SERU Consortium and senior researcher at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education.

Compared to their domestic peers, international students reported higher levels of satisfaction with the support they received from their instructors to successfully learn online, higher levels of satisfaction with the overall quality of their courses that were moved online and higher levels of satisfaction with their university’s overall response to the pandemic.

Their primary concerns lie elsewhere. The top five concerns cited by international students were:

- Maintaining good health while in the U.S. (cited by 52 percent of international undergraduate students and 67 percent of international graduate students)

- Managing immigration status and visa issues (cited by 44 percent of international undergraduate students and 55 percent of international graduate students)

- Having adequate financial support (cited by 36 percent of international undergraduate students and 49 percent of international graduate students)

- Understanding U.S. medical insurance and obtaining health services (cited by 35 percent of international undergraduate students and 53 percent of international graduate students)

- Securing a job in the U.S. after graduation (cited by 28 percent of international undergraduate students and 51 percent of international graduate students).

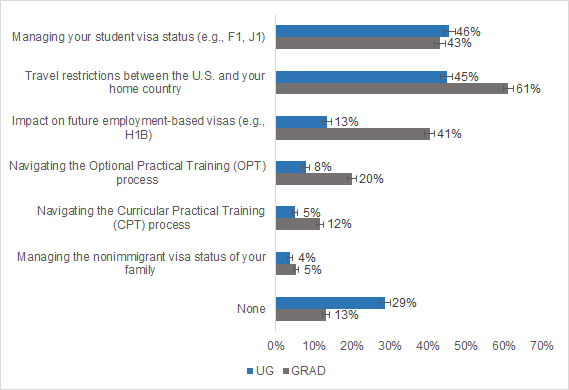

In regards to immigration and employment issues, international students reported concerns about managing their student visa status; travel restrictions between the U.S. and their home countries; the impact on future employment-based visas, such as H-1B visas; and navigating the optional practical training program, which allows international students to work in the U.S. for up to three years after graduating while remaining on their student visas.

There is good reason for international students to worry about changes to employment-based visas and other programs that allow them to work in the U.S., given recent moves by the Trump administration to limit immigration.

There is good reason for international students to worry about changes to employment-based visas and other programs that allow them to work in the U.S., given recent moves by the Trump administration to limit immigration.

President Trump issued a proclamation last week suspending entry to the U.S. by foreign nationals on H-1Bs (notably, the data in the SERU survey, collected on or before June 11, predates the proclamation).

And while the administration has so far spared the popular OPT program, advocates for international students remain highly concerned Trump may yet move to end or curb OPT through regulatory changes.

The SERU survey also found that about a quarter of international students were concerned about xenophobia, harassment and discrimination.

Seventeen percent of international undergraduate students and 12 percent of international graduate and professional students reported they had personally experienced instances of intimidating, hostile or offensive behavior based on their national origin during the pandemic.

The rates were higher -- ranging from 22 to 30 percent -- for students from China, South Korea, Japan and Vietnam. Reports of anti-Asian racism have increased since the start of the pandemic, but the survey did not ask whether these instances perceived as discriminatory were directly tied to the coronavirus.

About half of students who experienced behavior they perceived as discriminatory said it affected their mental health: this was true for 43 percent of undergraduates and 55 percent of graduate students. Slightly less than a third (30 percent undergraduate and 29 percent graduate) said it interfered with their relationships with American peers or friends. Seventeen percent of undergraduates and 22 percent of graduate students said discriminatory incidents interfered with their academic or professional performance.

While the survey found that international students as a whole reported adapting better than domestic peers to remote learning, there were big differences across nationalities. For example, the percentage of undergraduate students from China who said they adapted well or very well to remote instruction was, at 69 percent, much higher than for students who came from Mexico (59 percent) or India (41 percent). Chirikov said differences in students' fields of study may account for some of these differences, a subject he plans to dig into in future research.

And students who returned to their home countries during the pandemic faced unique challenges. Thirty-eight percent of international undergraduates who left the U.S. after the pandemic started reported obstacles attending courses during their scheduled meeting times. The survey report suggests that faculty and staff working with international students abroad "should be mindful of this subpopulation and offer accommodations or asynchronous alternatives, where possible."