You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

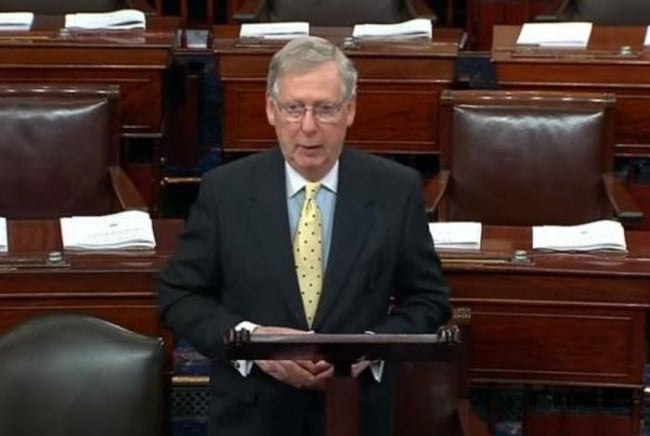

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell speaks on the Senate floor.

Office of Senator Mitch McConnell

Advocates who have been pushing for student loan debt to be canceled were disappointed that, even with a $2.2 trillion price tag, the stimulus package approved by the U.S. Senate late Wednesday night doesn’t do more.

The president of the umbrella association representing colleges and universities also expressed disappointment, saying the amount of aid for higher education institutions in the bill is “woefully inadequate.”

So even before the Senate sent the relief package to the House, lobbyists were looking ahead to the next stimulus package, which Congress has already begun discussing.

“This isn’t the last bus,” said Terry Hartle, the American Council on Education's senior vice president for government and public affairs, after his group calculated that the bill contains about $14 billion for higher education institutions, far less than the $50 billion they requested in emergency aid.

It’s unknown what the next package would focus on, but with both K-12 and higher education groups complaining about being shortchanged this time, Congress could consider adding education funding, Hartle said.

Throughout the debate over the bill, advocates for student loan borrowers, such as the Young Invincibles, were pushing Democratic proposals in the House and Senate under which the federal government would have made payments on behalf of borrowers and reduced their balances by at least $10,000.

On Wednesday, Kyle Southern, higher education policy and advocacy director for the Young Invincibles, a millennial advocacy group, said, "Congress has done the basic duty for students and borrowers by holding them harmless for now." But, he said, "for people carrying a heavy load of student debt, this bill just places it farther down the trail for them to pick up again."

Under the measure, borrowers with federally held loans will be excused from making their monthly payments, without interest on their balances accruing, for six months, through Sept. 30.

“This bill will keep payroll checks coming to workers during the crisis, relieve financial burdens on Americans during the crisis,” Senator Lamar Alexander, the Tennessee Republican and education committee chairman, said in a statement.

The moratorium on making payments would extend the 60-day break, Betsy DeVos, the U.S. education secretary, announced last week. Some financial aid experts had worried that the temporary waiver on interest President Trump also announced could lead to problems because it required borrowers to contact loan servicers.

But Justin Draeger, president and CEO of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, said that based on what he’s been able to learn about the Senate bill, it appeared to make the moratorium on payments and interest automatic.

Draeger also was pleased the bill included a number of provisions to relax or clarify current regulations on behalf of borrowers, including not requiring Pell Grant recipients to repay the federal government if they had to leave school because it closed due to the crisis, as well as not counting disrupted academic terms toward the lifetime limit on receiving Pell. The bill also says canceled classes would not count against a student’s satisfactory academic progress calculation, according to the National College Attainment Network.

Still, as first reported by Inside Higher Ed Tuesday, the bill does not include any debt cancellation, except for a provision that forgives debt incurred in an academic term that ends up being disrupted by the pandemic.

While the suspension of payments helps in the short term, advocacy groups had wanted debt to be canceled, anticipating that borrowers will have a hard time making payments even after the crisis ends, as the economy gears back up.

Debt Cancellation as Sticking Point

Chuck Schumer, the Democratic Senate minority leader, acknowledged on the Senate floor Wednesday afternoon that the bill does not go as far as advocates wanted.

“This bill is far from perfect,” he said. “Many flaws remain, some serious. By no stretch of the imagination is this the bill Democrats would have written had we been in the majority … We would have included more relief for student borrowers.”

But a Democratic Senate aide said on Tuesday that “Republicans balked at the large-scale cancellation of student loans. We pushed until the end, but it’s not happening.”

In retrospect, Republican Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn telegraphed Republicans’ philosophical opposition to debt cancellation two weeks ago, even before the stimulus package came into shape, during a debate to undo DeVos’s new rule making it more difficult for students who were defrauded, mostly by for-profit institutions, to have their loans forgiven.

Speaking on the Senate floor, the Texas senator mocked Sanders, a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, saying his proposal to forgive all federal student loans was a fantasy and not financially responsible.

“To say we’re going to wipe away the debt is not fair to the parents who started to save for their kids’ college even before they started walking or the college student who worked multiple jobs to graduate to work with little or no debt at all,” Cornyn said. “Or decided to go to a community college at a lower cost before they transferred to a four-year institution and found a way to mitigate or keep their debt manageable. And of course this idea of wiping away debt or making everything free is unfair to the person who chose not to go to college only then to be saddled with someone else’s debt.”

Speaking on the Senate floor Tuesday, before the announcement of the deal, Senator John Barrasso, a Republican from Wyoming, described the Democratic proposals for the emergency as a “liberal wish list” that included a “student loan giveaway.”

The stimulus measure is expected to pass the House, though House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was unsure how to conduct a vote given the crisis. But some, including Ilhan Omar, a Minnesota Democrat, raised concerns that the Senate bill would not cancel loans.

Medical colleges, however, were happy about a $100 billion emergency fund for health-care providers, which could benefit teaching hospitals.

David Skorton, president and CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said in a statement that the fund "will help stabilize teaching hospitals and faculty physician practices that are challenged by lost revenue attributable to the treatment of patients during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak -- losses estimated at millions of dollars per day."

Meanwhile, Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, said in a statement Wednesday that the bill includes some easing of regulations, which institutions sought, and excuses student loan borrowers from making payments for six months. He added, though, that "in this area too there is more that could be done."

But, Mitchell said, “we cannot stress enough that overall, the assistance included in the measure for students and institutions is far below what is required to respond to the financial disaster confronting them.”

Based on the information available Wednesday afternoon, ACE estimated the bill provides far less than the $50 billion in aid requested by institutions.

The latest bill provides $30.75 billion for coronavirus-related aid for all of education, of which 47 percent is earmarked for higher education, about 43 percent for K-12. (States can use about 10 percent for education at their discretion.)

Higher education’s share of the $30.75 billion comes to about $14 billion.

Of that $14 billion, 90 percent was earmarked to go to institutions. And of that $12 billion, 75 percent would be distributed based on the enrollment equivalent of full-time students who are eligible for Pell Grants, favoring large colleges with large numbers of low-income students. The other 25 percent is distributed according to non-Pell enrollment. Those only taking courses online before the crisis don't count.

The remaining 10 percent of the $14 billion for higher education is divided between historically black colleges and universities and grants for small institutions impacted by the pandemic.

The discretionary funding for states carries a requirement that states not reduce funding for higher education.

But Craig Lindwarm, vice president of congressional and governmental affairs at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the requirement doesn't do enough to protect institutions from state budget cuts. States could seek a waiver from DeVos if they are in financial crisis. And to determine if they are maintaining a level of spending for higher education, the feds would look at a three-year average for spending. But if, for example, a state increased spending in 2019 and 2020, counting the lower spending in 2017 would lower the three-year average. Indeed, Lindwarm said the three-year average of 48 states is lower than what they are spending on higher education this year.

"We know when states are under immense financial pressure public higher education is often the first target for cuts because state policymakers can shift costs to students and families. We are deeply concerned that this will happen again like in the last recession and the maintenance of effort provision provides minimal protection,” he said.

In addition, the Senate bill didn't fix a problem in the prior stimulus package Trump signed into law last week. It required public institutions to offer extended paid leave. But unlike private businesses, colleges are not eligible for a federal tax credit to defray the cost.

Lindwarm also was looking forward to the next round of stimulus to fix those problems and to try to get additional funding.

“While this legislation is an improvement from where the Senate started, the amount of money it provides to students and higher education institutions remains woefully inadequate,” Mitchell said in a statement.

“Every college in the country is facing a cash flow crisis,” Hartle said. “Federal support will help, but we don’t think it will be enough,” he said, noting that on Tuesday, Central Washington University cited financial exigency and the Art Institute of San Francisco announced it will not accept any more students and will be laying off faculty because of the crisis.

“That’s a school that survived the great earthquake and two world wars. But it’s facing a swift end because of coronavirus,” Hartle said.