You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jeff Reinking via Getty Images

Ashley-Shae Benton, a student at the University of Louisville, was “stunned” to hear about an anti-gay incident that recently occurred on campus. It was not something she expected at a university known for being welcoming of people of all sexual identities.

“Since the time I’ve gotten here, Louisville has preached about inclusivity,” said Benton, a senior who came out as lesbian four years ago. “Students are prideful about being out in their sexuality. Coming to Louisville was my saving grace. I was able to come out and be myself. But now it makes me question whether I should be out.”

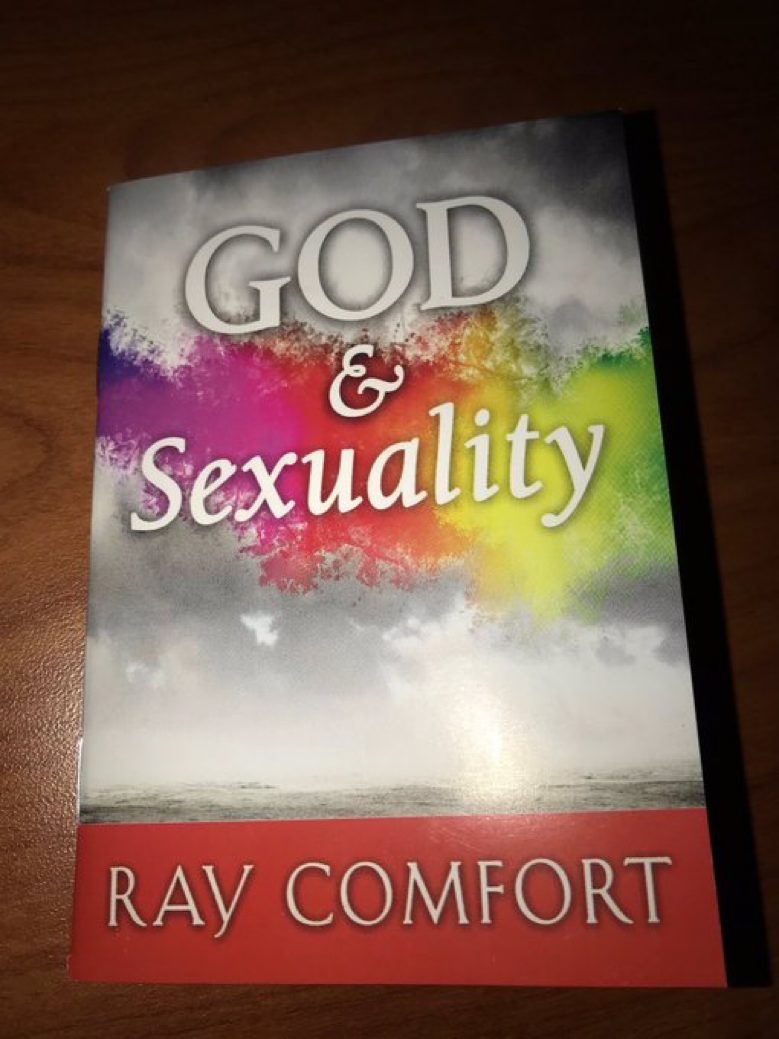

Benton is not the only student worried since a fellow student entered a classroom where an Introduction to LGBTQ Studies course is taught and placed a pamphlet equating homosexuality with sin on each desk. The pamphlet was titled “God and Sexuality,” said Charlotte Haydon, a student in the class. The more than 30-page pamphlet, published by the Christian organization Living Waters, starts off by describing a woman locked in a car that is sitting on train tracks and about to be hit by an oncoming train and likens the dangerous scenario to being gay or “sympathetic toward homosexuality,” reported The Courier Journal, a Kentucky newspaper.

“I want to convince you that you are sitting in a car on a railroad track with a train coming, and you don’t know it,” the pamphlet said.

The young man who left the pamphlets, was not enrolled in the course and arrived 20 minutes before the start of the class to distribute the pamphlets. The professor who teaches the course said he then "lurked outside" in the hall once the class began, The Courier Journal reported. The entire episode left many LGBTQ students in the class and on campus feeling unsettled and unsafe, especially after the university said the student was within his rights when he visited the classroom to distribute the literature and could not be legally prevented from returning and doing the same thing again.

Haydon, a first-year transfer student and trans woman, said she and others in the class felt targeted and uncomfortable. She later learned that the student waited outside the classroom while it was in session and hid in a spot where he could not be seen by the students but could see them. Haydon believes such behavior constitutes stalking.

“So far we haven’t seen a whole lot about what that inclusivity means because we weren’t able to take action against a student who was invalidating our existence,” Haydon said. “At the moment, it’s just one of those things that Louisville is going to have to stand by or it’s going to lose its credibility.”

Under Kentucky law and university policy, students cannot be prevented from entering classrooms and expressing their free speech rights, unless a class is in session and as long as they are not disrupting a class, said John Karman, the university's director of media relations.

The Dean of Students' office has spoken with the student, whom the university did not name, and determined he made no threats and did not “exhibit any violent behavior” or “express the wish to harm anyone,” Karman said.

"According to our attorneys, the pamphlets he was distributing did not qualify as hate speech," Karman said. "He’s expressing his First Amendment rights, and he’s allowed to leave the literature."

Still, university administrators decided to place a police officer outside the classroom where the Introduction to LGBTQ Studies course is taught for the remainder of the semester, he said.

Karman said Louisville's policy follows a Kentucky campus free speech law enacted in 2019 that broadly protects the First Amendment rights of faculty members and students. Under the law, which mirrors several other campus free speech laws enacted by various states over the last four years, the university and other public institutions in the state are required to guarantee that the “free exchange of ideas is not suppressed because an idea put forth is considered by some or even most of the members of the institution’s community to be offensive, unwise, disagreeable, conservative, liberal, traditional, or radical,” the law states.

The legislation outlaws “free speech zones” on campuses, prohibits viewpoint discrimination against invited speakers and in the fees associated with bringing speakers to the campus, and allows “spontaneous outdoor assemblies or outdoor distribution of literature” without a permit. The law does not explicitly discuss assembly or distribution of materials inside institutional buildings, but it does mention free classroom expression in reference to academic assignments and discussion.

The Kentucky Family Foundation, a Judeo-Christian organization, was supportive of the law when it passed through the state Legislature last spring, said Martin Cothran, a spokesman for the foundation. He said foundation members are at “at odds” with many political positions held by the LGBTQ community and believe marriage should be between men and women.

“We are concerned about this idea that if you don’t agree with gay rights groups, that your opinion should somehow be restricted in some way,” Cothran said. “This has been a problem at the University of Louisville for a number of years -- there’s safe spaces for gays who are celebrated and no safe spaces for conservatives who are in many cases ridiculed.”

More than 17 states have enacted similar laws to reinforce First Amendment rights on college campuses, according to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE, a civil liberties watchdog organization.

But the laws should not prevent professors from being able to lead and moderate class discussions without outside interruption, said Adam Steinbaugh, director of FIRE’s individual rights defense program.

“To the extent that the university is telling students they cannot obstruct a class, that is not objectionable,” Steinbaugh said. “I think if they are outside of a classroom, as long as they are not preventing coming or going from the class, I think they can be allowed to do so, so long as that is a non-disruptive and viewpoint-neutral policy.”

If the student continues to repeatedly target students who clearly do not want to interact with him, it could eventually be considered harassment, in which case the university could respond, Steinbaugh said.

“Once or twice does not amount to hostile harassment under the law, and absent a hostile environment, the university cannot punish someone for their speech,” Steinbaugh said. “If he’s preventing students from learning, that would be cause for the university to do something.”

Louisville’s Code of Student Rights and Responsibilities does say students and organizations “must not in any way interfere with the proper functioning of the university” and that the university “reserves the right to make reasonable restrictions as to time, place, and manner of the student demonstrations.”

“While the student’s actions caused concern among the students and faculty in the classroom, he apparently followed the law and university policy when distributing the literature,” Karman said in a statement. “The university values diversity in all its forms, including diversity of opinion. That said, student safety is our top priority. We will continue to monitor the situation and will take steps to ensure an environment that supports the highest level of learning.”

That's not how some students and faculty see things. Ricky Jones, chair of the Pan-African studies department, wrote in an opinion piece for The Courier Journal that Louisville “made the decision to interpret” the state and university policy in a way “that did not cast the student’s behavior as menacing, harassing or impinging upon other students’ ability to learn in peace.”

Jones, who did not reply to requests for comment, wrote: “U of L has made it clear that it is more concerned with a possible lawsuit from the student or conservative backlash than the protection of a faculty member and rattled students who are being targeted and harassed because of their sexual orientation.”

Some students, especially those in the LGBTQ community who now question their safety on campus, are not satisfied with the “neutral standpoint” the university has taken on the issue, Benton said.

“Today it could be propaganda, and tomorrow it could be violence,” she said.

Haydon said the incident has disrupted the LGBTQ Studies class, which has not been able to return to regular coursework since the incident occurred.

“The distinguishing feature is if he was handing things out on campus, he didn’t have the motivation to seek people out,” Haydon said. “He was willing to spread hate speech and actively seek groups of people out that he doesn’t agree with on a fundamental and unfounded basis.”

University president Neeli Bendapudi and other administrators met with students and Professor Kaila Story, who teaches the course, during their class time on Feb. 6 and explained why the university was limited legally in how it could respond to the incident, Haydon said. Story did not respond to requests for comment.

“I can understand the standpoint. I don’t necessarily agree with it, but I can understand that that’s the way it is. It speaks a lot to the state of the country,” Haydon said. “It prompts a discussion on what we can do as a university, as a community, to address the needs of people who are targeted by hate speech.”

Students suggested to Bendapudi a few ways to improve inclusion of the LGBTQ community on campus, including not making the meeting times and location of LGBTQ studies courses public, and mandating a freshman course on the LGBTQ community, Haydon said.

“She seemed really open and receptive to these ideas, and I really hope these are followed through on,” Haydon said. “These are really good solutions -- the issue is having them enacted.”