You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/PeopleImages

A set of federal programs created more than a decade ago to help struggling student loan borrowers appears not to have made a significant dent in the default rates of one particularly vulnerable group: black borrowers.

An analysis of federal data released by the Center for American Progress Monday shows that African Americans who entered college in 2011 and took out federal student loans defaulted on those loans at sharply higher rates than did their peers of other races.

The think tank's report is a follow-up to 2017 data revealing that nearly half of all black borrowers who entered college in 2003-04 had defaulted on at least one loan within 12 years of initial enrollment. Those data -- which were the first time federal data had been broken down by race -- surprised many higher education officials and policy makers.

The author of the center's new report, Ben Miller, notes in the report that policy makers might have hoped that the cohort of students who entered college in 2011-12 would fare better because they enrolled after the creation of new federal programs that link borrowers' repayment to their income. Those programs were specifically designed, Miller wrote, "to help individuals struggling with debt."

But the new data suggest little to no improvement in the fate of black borrowers despite the new repayment options.

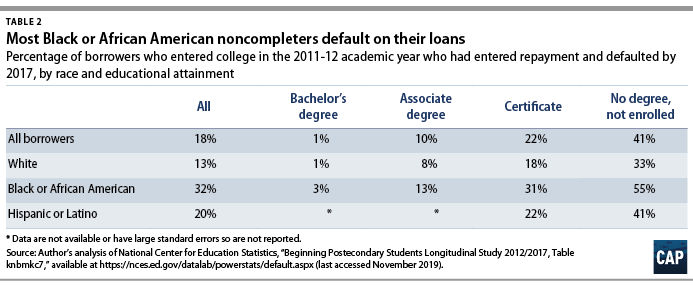

As documented in the table below, African American borrowers who entered college in 2011-12 and had entered repayment by 2017 were significantly likelier than their white and Latino peers to have defaulted on their loans at some point in those six years.

As is true of many college students who default on student loans, struggling borrowers in this study typically didn't borrow very much -- the median defaulter had just $6,750 in debt.

Many of them, however, had not earned a college credential. The table below shows that borrowers who had completed a degree (associate or bachelor's) had much lower rates of default than did their peers, while those who had left college and failed to earn a credential were much likelier to default.

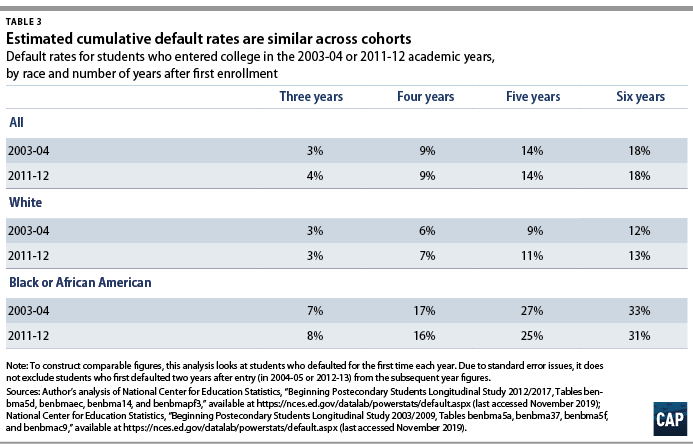

Those data are not exactly analogous to the data contained in the 2017 reports, which covered the entering class of 2003-04 -- those borrowers had six additional years of repayment history to examine.

To try to approximate some way (even if imperfect) of comparing the two sets of borrowers, Miller pulled data on those borrowers who took out loans in their first year of enrollment (either 2003-04 or 2011-12) and therefore would have started repaying their loans within six years of enrolling.

As noted in the table below, the figures for the two groups are roughly analogous. "These numbers suggest that, at the very least, default rates have not gotten substantially better over the eight years between the two cohort entry points," Miller writes.

The borrowers who entered in 2011-12 had some potential advantages over their peers who enrolled eight years earlier, notably the creation in the intervening years of income-based repayment plans that were designed to calibrate borrowers' loan repayment if their earnings were below certain thresholds.

The study finds that black borrowers were slightly likelier than their peers of other races to participate in one of the government's several income-driven repayment programs -- and the data suggest, the report states, that the programs are helping black borrowers stay out of default.

But the fact that black borrowers continue to default at much higher rates than their peers suggest that income-driven repayment alone is an inadequate solution, Miller writes. "Such worrisome results, even with the availability of IDR, suggests that repayment plans that reduce monthly payments are a necessary but ultimately insufficient tool for addressing loan default."