You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Weeks after it allowed a known harasser to attend a conference where three of his accusers were present, the Society for American Archaeology is still mishandling the incident. That’s what scores of academics are saying in open letters, social media posts and other correspondence with the organization.

Specifically, critics say that the society hasn’t addressed questions and concerns about the actions it took -- or didn’t take -- during and after the conference. They’re also asking why the society has deleted tweets about the incident and blocked several conference attendees on social media.

The society has expressed some regret about how it handled the matter and said it’s committed to dealing with harassment. But the lesson to other professional organizations is clear: while privacy and process concerns abound in harassment cases, sexual misconduct is a public issue requiring a transparent, coherent response to member concerns.

“I did not think that the Me Too issue that arose at the SAA conference over two weeks ago would still be going on,” Kristina Killgrove, teaching assistant professor in anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said Monday.

Instead, said Killgrove, who publicly stepped down as chair of the society's media relations committee over the incident, “I expected that the Board of Directors and the SAA staff would immediately identify what went wrong and work with the survivors of Yesner's harassment to come to an appropriate resolution.”

Killgrove was referring to David Yesner, a former professor of anthropology at the University of Alaska at Anchorage. He formally retired in 2017 but was recently denied emeritus status over a wave of student allegations of misconduct spanning his long career. He hasn’t commented on those accusations. But a university investigation found them so credible that Yesner is banned from campus and all university events. Anchorage even alerted students earlier this month to tell the police if they saw him around.

The Alaska Anthropological Association notified members that Yesner was banned from its events, too. But Yesner was allowed to register on site for the SAA conference starting April 10 in Albuquerque, N.M. The SAA has since said that it received complaints about Yesner’s presence on April 12 and asked him to leave that same day, as soon as it confirmed the allegations against him with the Anchorage campus. But three of Yesner’s targets who have identified themselves online say that they missed out on much of the conference due to Yesner’s presence.

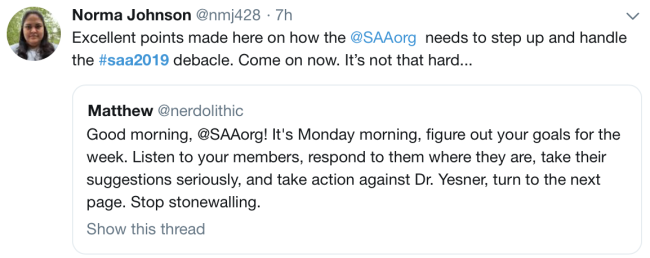

Norma Johnson, a graduate student in archaeology at Anchorage and one of nine women who brought substantiated complaints against Yesner, confirmed Monday that she has had two phone calls with the organization but no resolution. Johnson also said that the society was aware of Yesner’s presence at the conference on April 11, not April 12.

Before Yesner left the conference, the SAA booted out science journalist Michael Balter for confronting him. Balter believed he was acting on behalf of the student accusers, including Johnson. He was also at the conference to speak on a panel about Me Too. But the society later tweeted that Balter was not in attendance as a "credentialed journalist.” The tweet has since been deleted.

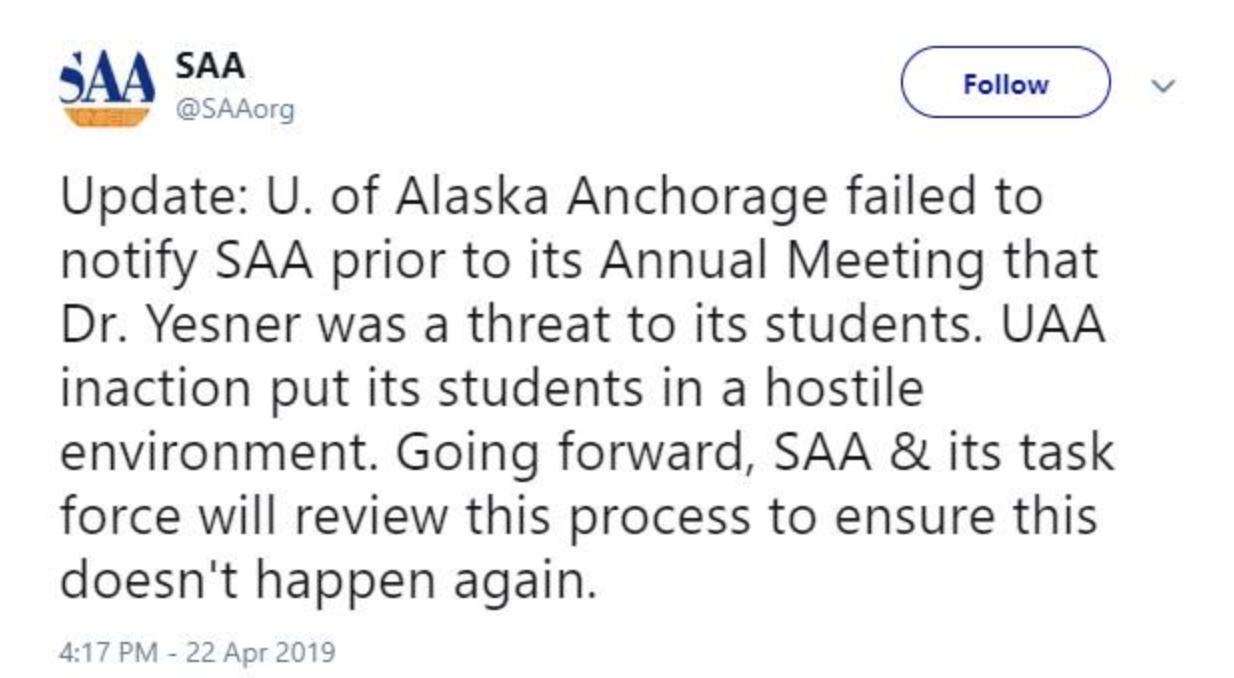

The SAA Twitter account also appeared to blame Yesner’s former institution for not alerting it to its findings about Yesner. That tweet is now gone, too.

In response, the university has said that its conference attendees communicated their concerns to the society on April 11, and that its arts and sciences dean followed up with his own email to the SAA that evening.

“Absent any response from SAA,” Chancellor Cathy Sandeen also emailed on April 12, the university said in a statement. The campus was not a co-sponsor of the conference and Yesner had not been an employee since 2017, so Anchorage had no reason to anticipate his attendance, “particularly given recent publicity.”

That said, the university continued, “when conference organizers failed to respond promptly to students concerns we acted swiftly to ensure the safety of our students.”

More recently, the account blocked both Killgrove and Balter on Twitter.

Both have been publicly critical of the organization. But “blocking two of the most vocal people on Twitter is problematic given the history in the field of archaeology of silencing people who address harassment and assault,” Killgrove said.

The SAA has deleted other tweets about the incident -- along with critical replies. Some allege this amounts to censorship, or at least a major public relations flub. One of those tweets was about a task force to address sexual harassment and assault.

Early member replies to that announcement criticized the task force idea as a kind of nonresponse response, or kicking the accountability can down the road. But members were surprised to see the society erase the tweet and the subsequent criticism, rather than allow the debate to play out.

Jason De León, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan, in a public Facebook post asked the society to cancel his membership, effective immediately.

“I decided to attend your conference this year because of my involvement in the #MeTooInArchaeology session,” he wrote. “I was feeling overly optimistic that your organization was primed to be at the forefront of helping our discipline overcome its legacy of sexual harassment, assault and various forms [of] discrimination and inequality.”

Yet the last two weeks demonstrated that “my optimism was unfounded,” De León said. “Your organization has serious problems related to equity, diversity and basic human sensitivity. I keep thinking that your Twitter account responses to the Me Too issue is some employee gone rogue, but in many ways the tone-deafness of your Twitter account perfectly encapsulates the culture of your organization.”

Holly Norton, archaeologist for the state of Colorado, left the society and its Committee for Government Affairs on similar terms. Numerous other society members have publicly parted ways with the organization or otherwise declared their disappointment with it.

The Committee on the Status of Women in Archaeology also spoke out.

Joe Watkins, president of the society’s Board of Directors, said via email that the last two weeks “have shown me, the SAA Board of Directors and the SAA staff the enormity of the systemic problem related to sexual harassment and how women are treated” in the field.

“We are at a tipping point for our profession, and we feel we have not done enough to address the systemic issue of sexual harassment in archaeology,” he continued. “That said, I have personally reached out by phone or email to the survivors. We regret that we were not able to act sooner, and we sincerely apologize.”

The kinds of “changes being discussed require that we conduct professional and mindful conversations online and off,” Watkins added. “This isn't about placing blame or going over what we did wrong in the past. This is about how and what we need to do next.”

What should that be? Members have offered their own advice to the organization -- starting with an action document that’s been signed by more than 2,300 people. That includes issuing a formal apology, refunding conference registration fees to aggrieved parties, and updating the society's anti-harassment policies and procedures.

Sarah M. Rowe, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Texas at Rio Grande Valley, shared her thoughts with the organization in a public letter on Facebook. (Rowe previously reached out to the organization, asking for a more thorough response to members’ concerns, and said she received what was essentially a form letter in response.)

Rowe’s advice for what she calls a “society in crisis” includes short-term and long-term actions. Needs include communicating with all three women targeted by Yesner, revoking Yesner’s membership, addressing the society’s full membership via email -- and firing whoever is behind the SAA's social media.

Adopt policies already in place at other organizations, so that someone under investigation should not be allowed at meetings until the case is resolved, Rowe also advised. Institutional censures should translate to society event bans.

Norton, of Colorado, has said publicly that she was asked to serve on the task force but declined. She said Monday that she didn’t feel like it was a good use of her time, "as there were too many unknowns and not enough accountability,” in that "it feels even more like howling into the wind than Twitter.”

At this point, she said, the society should hire an outside consultant to assess problems within its system for dealing with harassment and then act accordingly.

“Ultimately,” Norton added, "the board needs to act and respond, and they just seem paralyzed at the moment.”