You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Brian Goegan, former ASU professor

Arizona State University

A former professor's public accusation against Arizona State University's “highly unethical” grading practices has devolved into a case of dueling recriminations. And despite being widely discussed on social media, it's still unclear where the truth lies between the disparate perspectives of the professor and the institution.

Brian Goegan, who was a clinical assistant professor of economics at ASU, says he was fired for failing to adhere to grading quotas.

ASU officials flatly deny this. They said there were no such quotas and implied that Goegan was fired for his "multiple shortcomings" as a professor.

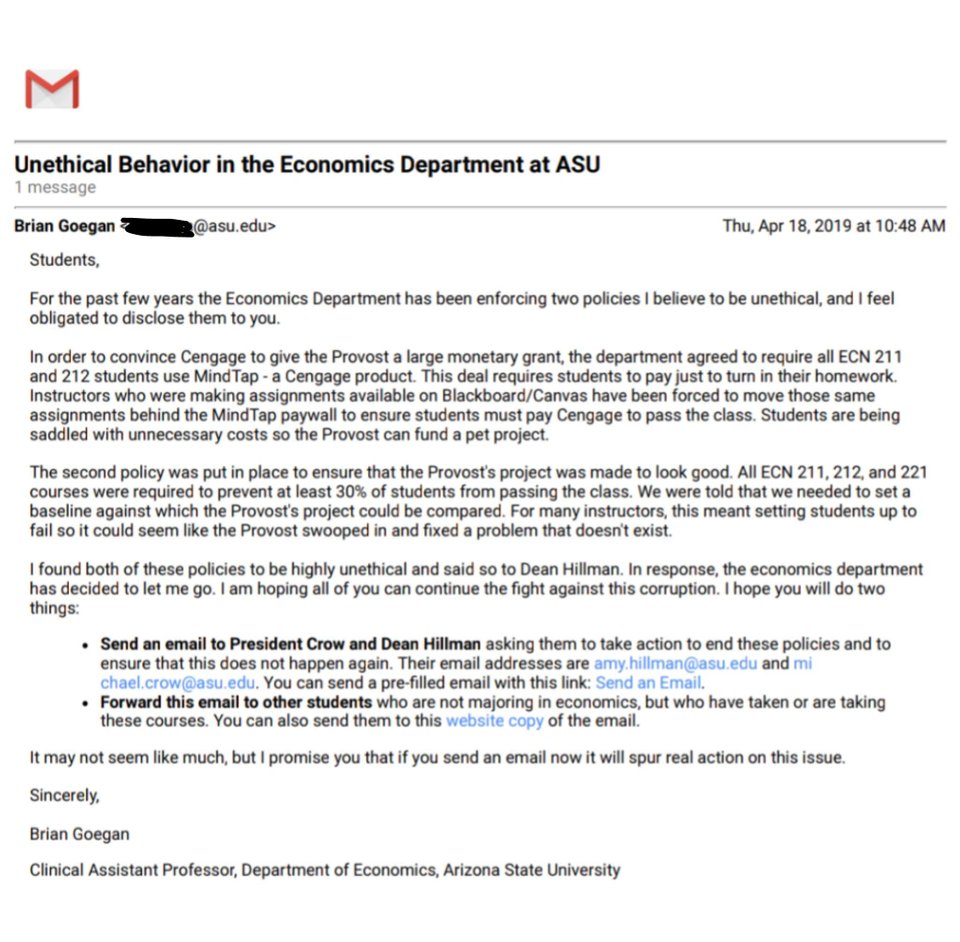

The kerfuffle was prompted by an email Goegan sent to his students on April 18, which was then shared on Reddit, saying he was forced out for pushing back on a requirement to fail 30 percent of his class. He said the alleged mandate was issued in order to falsely inflate the positive impact of a new digital courseware product on students’ grades.

The courseware is a homework and assessment platform called MindTap which tests students' knowledge of material covered in an associated digital textbook. Goegan was required to start using the platform in 2018 and says he was fired after he continued to voice concern about the department's policies regarding the courseware to his supervisors.

Mark Searle, executive vice president and university provost at ASU, responded in a written statement Friday, saying the university had investigated Goegan’s claims and “found no factual evidence to support them.”

“The accusation that the university would establish quotas in any course requiring to fail a certain percentage of students is unequivocally false. That is not who we are,” Searle said.

Goegan posted a rebuttal to Searle's statement the same day. Goegan said he was troubled by how his department selected the new courseware. He claimed that ASU had received a “large monetary” grant from Cengage, an educational technology company and publisher, which owns the MindTap platform.

He said the grant was put toward an institutionwide adaptive learning initiative called the Principles Project. And in exchange for this funding, his department started to require the use of the MindTap platform in introductory-level economics classes.

Searle denied that there was any such deal.

“Cengage has not given ASU any grants,” he said. Cengage published a corroborating statement saying the company has never paid any grants to ASU.

Searle also refuted Goegan’s suggestion that he was fired after speaking out. “There are many reasons that a faculty member’s contract might not be renewed, including when a faculty member resists course correction of multiple shortcomings despite supervisory intervention.”

Though Searle denied that students are required to pay to turn in their homework, he acknowledged there is a course fee to access the MindTap platform.

“There is a fee to use MindTap, but it also pays for the class [digital] textbook,” he said. “The economics courses using MindTap are optional at this time; students may choose to take the same courses taught by other professors using traditional university grading/textbook platforms.”

Addison Wright, a junior at ASU, doesn't buy that explanation.

“They are blatantly lying about not requiring students to pay to turn in homework,” she said. “I have had to pay for homework for classes multiple times."

“This year I took a statistics class that required me to pay over $100 just to complete the homework,” said Wright. “I couldn’t afford the fee and ended up having to do the entire semester’s worth of homework in the two-week trial period.”

Wright, a graphic information technology major, took a class with Goegan in spring 2016. She, like many other students on social media, praised Goegan’s teaching skills and thanked him for publicly raising his concerns.

“He was incredibly passionate about economics and made it fun for the class to learn,” she said. “To this day he is the best teacher I’ve had at ASU.”

In a discussion thread on Reddit, some observers suggested students liked Goegan so much because his class was an easy A.

Wright disagreed. “I didn’t struggle passing it, but I know a lot of students were struggling.”

Goegan said that on average, around 30 percent of students got an A in his class, which was not easy. He attributed the proportion of A grades to a large number of honors students who chose his class. He said very few students withdrew from the class and he worked hard to help students succeed.

"I made sure that every assignment and test was comprehensive and difficult, but I was always willing to do whatever it took to help students figure it out," he said.

Goegan described a departmental meeting in July 2018 in which instructors for certain introductory economics classes were told to grade their students according to set percentages: 10 percent D’s, 10 percent E’s and 10 percent W’s (withdrawals). Goegan said this would set a new baseline against which the impact of the new courseware could be measured. When Goegan subsequently failed fewer than 30 percent of his students, he said he was formally reprimanded.

Goegan doesn’t have any written proof of the alleged mandate to fail 30 percent of his students. He does share an excerpt of an email showing a grade distribution for an introductory economics course, ECN 221, which he was told to follow. The distribution does not match the 30 percent failure rate Goegan said he was verbally told to adhere to. The grade distribution guideline called for 22% A’s, 36% B’s, 28% C’s, 5% D’s, 3% E’s and 5% W’s.

Robert Kelchen, assistant professor of education leadership, management and policy at Seton Hall University, said that it if Goegan was indeed asked to fail more students to set a new baseline, “the evaluation of the new materials would not be reflecting a real outcome.”

Asking professors to strictly follow a grade distribution is highly unusual, said Steven Greenlaw, professor of economics at the University of Mary Washington. If a professor is giving out too many A's, that might necessitate a conversation, but not a mandate to fail a specific proportion of the class, he said.

Greenlaw uses open educational resources in his classes with courseware from Lumen Learning which costs $25 per student. The MindTap platform and associated digital textbook -- a well-known title by economist Gregory Mankiw -- costs $99 per student.

Many students object to the concept of paying to do their homework, but Greenlaw said this is simply a new paradigm in higher ed.

"We're in transition from a period where the textbook was the product and the ancillary materials, be they study guides or homework problems, were thrown in for free," he said. "Now we're in a situation where the textbook is the commodity and the value added is in the ancillary materials."

Goegan said before the courseware shift at ASU, he would put assessments in the university’s learning management system at no cost to students. When he first started using MindTap, he made sure the homework assessments in the platform did not reflect a significant portion of students’ grades so that they could pass the course without paying the $99 fee. He was later told that MindTap assessments had to account for at least 20 percent of students’ grades.

Goegan believes the platform and textbook are overpriced.

"I know that relatively speaking it seems low for a textbook, but for that price you can buy just about any book in the world," he said. "I would joke with my students that they could buy all the Harry Potter books for that price and learn more from those than from the textbook."

Of course, Goegan's dispute with ASU is about more than money. It's also about upholding the principle of academic integrity.

“I had hoped they would conduct a more serious investigation,” he said. “It really appears to me that they are not at all concerned with actually addressing these issues -- they are only concerned with saving face.”

Goegan is now looking for a new job. He recognizes that speaking out may cost him professionally, but said he felt duty bound to tell his students what had occurred after his attempts to voice concern through official channels were unsuccessful. He encouraged his students to email the dean of the ASU business school and ASU president Michael Crow to complain. Goegan said he has been copied on over 600 emails from students so far.

“If they keep resisting students’ calls for changes to these politics, I think they need to take a hard look at whether or not they're truly keeping students' best interests at heart," he said. “I hope when people look at this situation, they consider that I wouldn't take this risk and jeopardize my future if it wasn't true."