You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

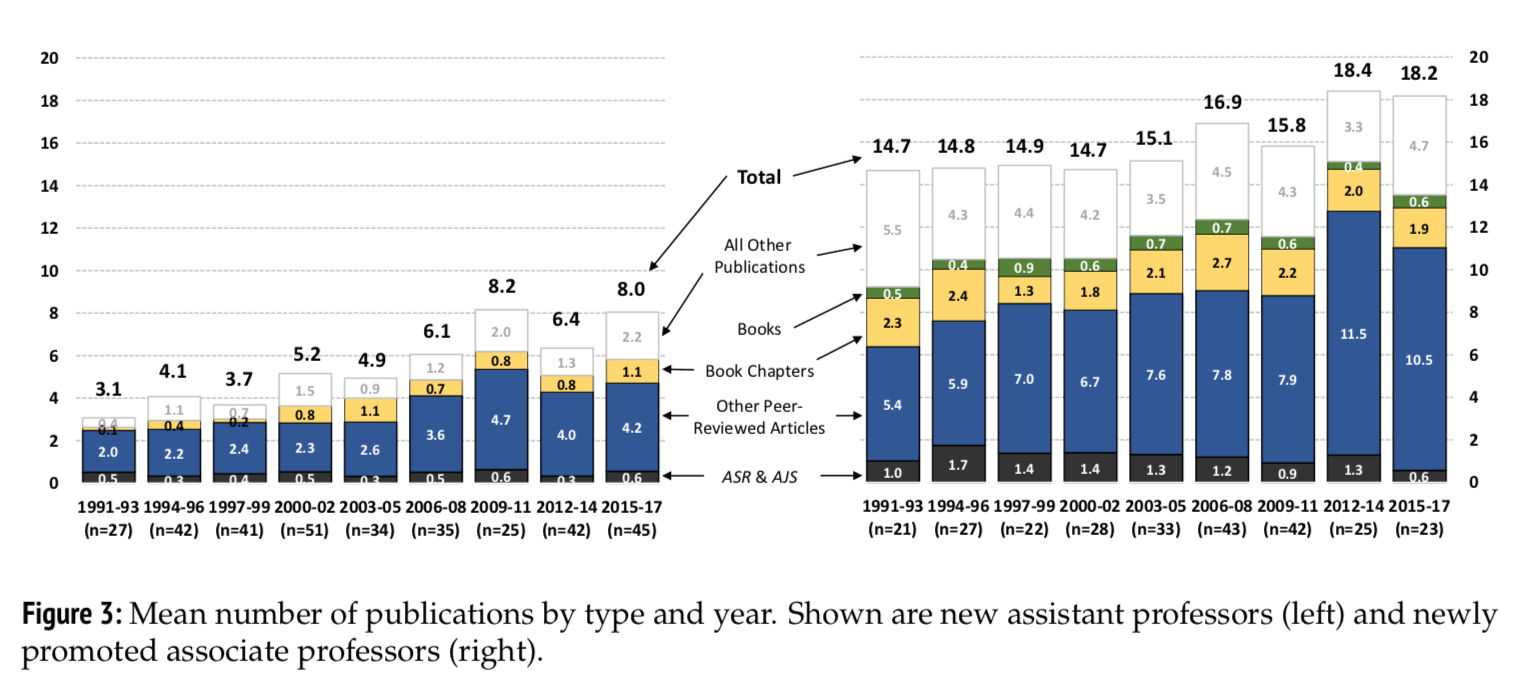

If it feels like publishing expectations for graduate students are way higher than they used to be, that’s because they are: brand-new assistant professors in sociology have already published twice as much as did newbies at the same highly ranked institutions in the early 1990s, according to a recent study in Sociological Science. Changing expectations for tenure over time are similar.

What does that look like, exactly? In 2017, new assistant professors at the 21 departments included in the study had published 4.8 peer-reviewed articles, on average, on their start date. About 25 years ago, the number was 2.5.

Newly promoted associated professors in article-centric subfields in the 2010s also published almost twice as many peer-reviewed articles as their counterparts two decades earlier. And even in book-centric subfields, the number of peer-reviewed articles has risen.

"Book people in the 2010s now publish as many articles as article people were publishing in the 1990s," reads the study, emphasis included.

“What I find, basically, is that the collective wisdom is correct: graduate students entering faculty positions today do publish much more than they did a generation ago, at least in top-ranked sociology departments,” author John Robert Warren, associate professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota in the Twin Cities, says in the study. “Likewise, in top sociology departments, successful candidates for promotion to associate professor publish more than they used to.”

Source: Warren

Warren’s primary purpose is to put data to anecdotes about “the good old days” of faculty work, versus now. But there are other reasons to examine this trend, he says. There is a perception that aspiring sociologists must work harder, more quickly and under greater pressure than ever before “to achieve the same rewards,” he says, “all with few additional resources” -- which may lead to greater anxiety and unhappiness among academics, especially junior scholars. And that may drive talented scholars, especially those trying to balance work and family life (read: women), from the field.

Rising publication exceptions also may “aggravate inequalities within and between sociology departments,” Warren says. That means between well-resourced “have” departments and the “have-nots,” and also among scholars working in article-based subfields and with existing data, who tend to publish relatively quickly, and those working in book-based subfields and who must gather their own research to analyze, who take much longer to publish.

All that might encourage junior scholars to choose subfields and design projects based on publishing speed, not intellectual interest. There are also questions of quality versus quantity. So in the “bigger picture,” Warren says, “rising publication expectations may thus affect the shape and direction of the discipline.”

Why are expectations changing? Warren explores a number of theories. Sociology departments may be more selective in hiring and promoting now than they were a generation ago, based on supply and demand: there are many more candidates than available jobs, for example, he says. And many more sociologists now take postdoctoral positions today than they did a few decades ago, meaning that new faculty hires may have had more time to publish than predecessors fresh from gradate school.

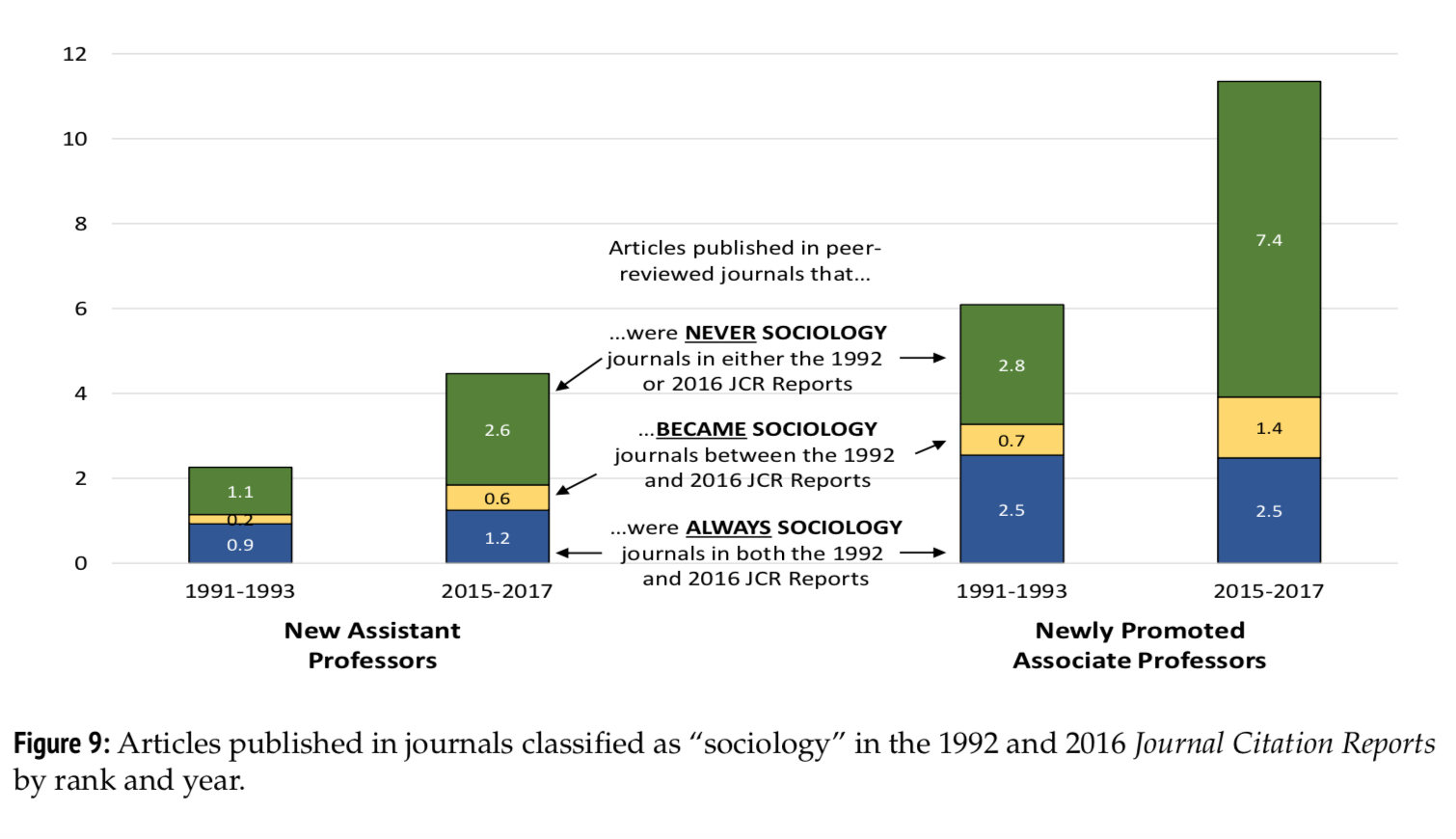

The structure of publishing also has changed over time: in 1986, the Social Sciences Citation Index’s Journal Citation Reports listed 64 journals about sociology, compared to 143 in 2016, Warren says. And, like scientists in many fields, sociologists have become more collaborative over time, co-authoring more papers. Warren also wonders if gender -- more women in the field, feeling they need to exceed expectations to succeed -- plays a role.

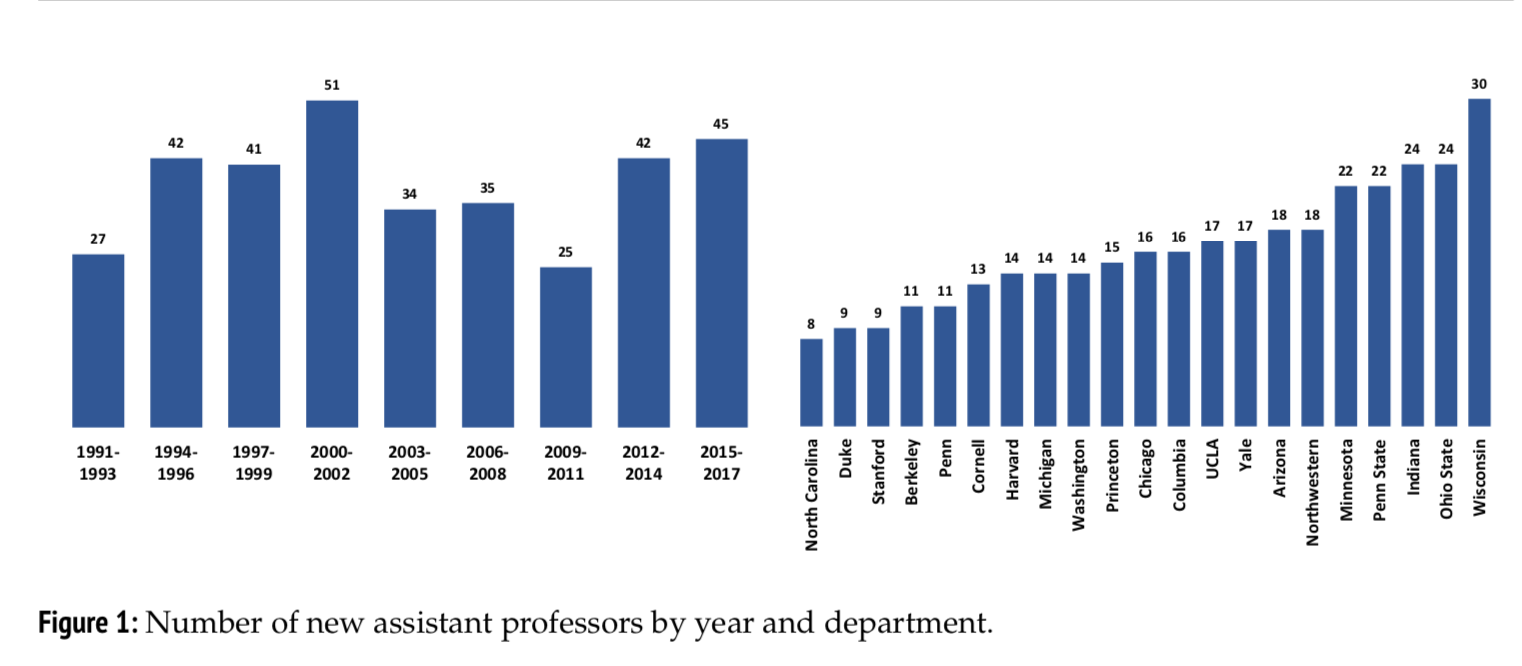

For his study, Warren looked at trends between 1991 and 2017 in how much sociology assistant professors had published on their first day on the job and when they were first promoted to associate professor. He narrowed his focus to the top 21 sociology Ph.D.-granting departments based on their inclusion in the 1992 and 2013 U.S. News & World Report rankings and in at least one of the National Research Council rankings. He found faculty members from 1991 to 2017 in these departments using publicly available data, such as websites and information from the American Sociological Association.

Warren says the elite department focus limits the generalizability of his research but makes the scope manageable. He also notes that these departments are “particularly influential in setting broader norms and expectations in the wider discipline,” as they produce a disproportionate share of all new Ph.D.s, “and (for better or worse) their faculties dominate journal editorships, editorial boards, grant-proposal review panels and leadership positions in professional associations.”

The faculty count turned up 342 new assistant professors in these 21 departments between 1991 and 2017. The number fluctuated over time, he said, with real dips observed during recessions. (Kieran Healy, an associate professor of sociology at Duke University, highlighted this -- and more -- in a mini-analysis on Twitter.) Warren used similar methods to identity 272 new associate professors in the same departments between 1991 and 2017.

Next, he counted peer-reviewed publications on the professors’ CVs, for their appointments as assistant professors and associate professors, respectively.

Of all possible explanations for the doubling of publishing expectations for getting hired and promoted, Warren says that the data most support the supply and demand/selectivity hypothesis and, possibly, technological advances that aid productivity. The number of new sociology Ph.D.s awarded has increased by 50 percent since 1991, but the number of new assistant professor positions has "not nearly kept pace," he says.

Among newly promoted associate professors, these same conclusions both hold. Increasing co-authorship -- especially in interdisciplinary fields -- also is a factor here, he says.

Linking all these forces, Warren says that as fiscal pressures on universities and departments have increased, “they may have found it easier and more financially beneficial to invest in hiring in areas in which it is possible to attract grant funds to support larger, collaborative, interdisciplinary projects.”

Asked whether he thought his findings would apply to other social science fields, Warren said recently that he suspected "the larger macro forces at work -- which really have to do with the organization and financing of higher education -- apply at least to the other social sciences and economics."

In any case, he said, sociologists now face “much greater pressure to publish” and “to publish often.”

Echoing the “why” piece of his study, Warren said that his findings have potential “human consequences,” in that “it's stressful and may push otherwise qualified people out of the field.”

Expectation creep also has “implications both for the quality of scholarship -- which may go down as demands for quantity increase -- and for the topics that sociologists may choose to study,” he said.

In other words, the trend toward more publications might also mean a trend toward “topics or approaches that ensure quicker and more certain publication.”