You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

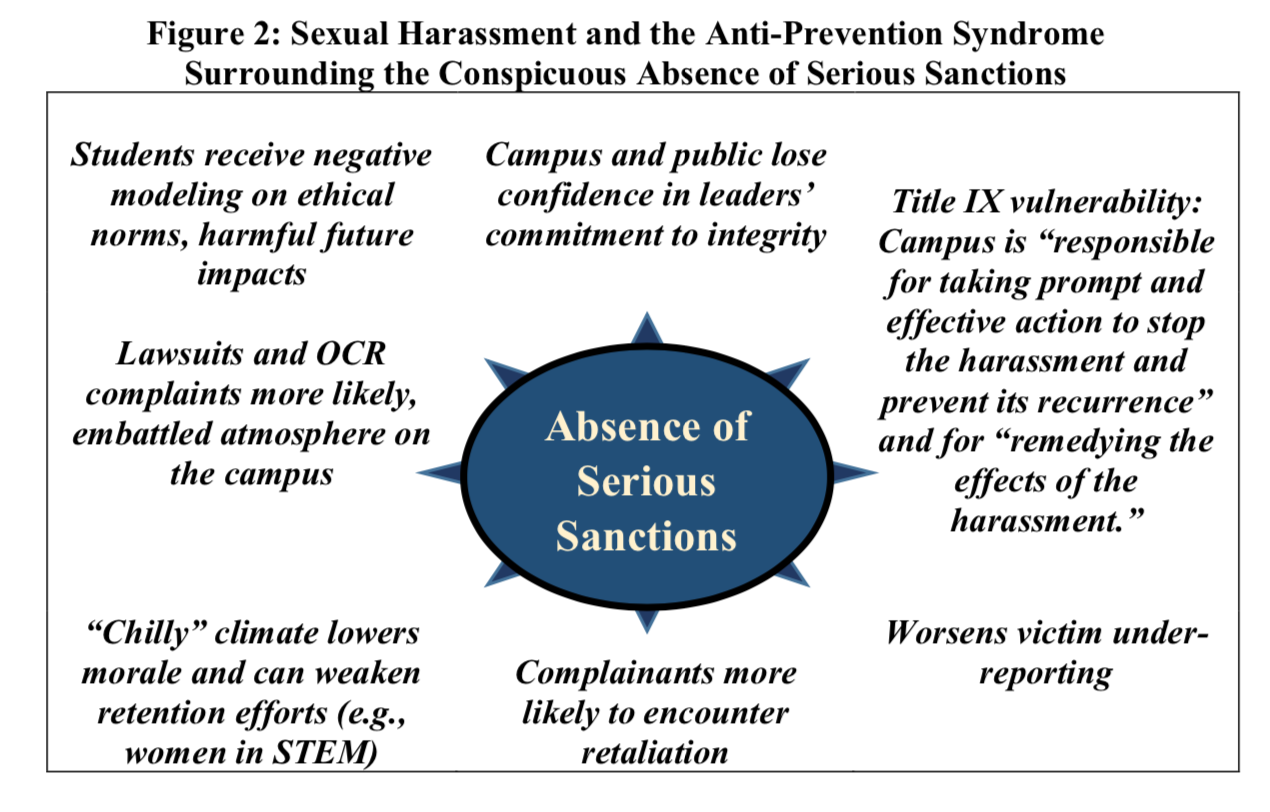

The absence of serious sanctions for faculty harassers is associated with “antiprevention syndrome,” which renders comprehensive prevention impossible, argues a forthcoming paper from Nancy Chi Cantalupo and William Kidder. And because institutions are legally required to prevent harassment and assault, institutions risk far more in failing to enact “meaningful discipline” than in shying away from it.

Kidder, research associate at the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, and special assistant to the chancellor at California's Santa Cruz campus, and Cantalupo, an associate professor of law at Barry University, are the team behind a 2017 analysis of nearly 300 faculty-student harassment cases. They found most harassers are accused of physical abuse -- not just questionable comments. That study, which centered on graduate students’ complaints about faculty members, also found that more than half of cases involved alleged serial harassers.

Their new paper, to be published in the UC Davis Law Review, is a companion to that analysis. The focus this time is accountability in organizational culture.

Some argue that focusing too much on disciplinary action to combat harassment is a mistake, the paper says, but “we disagree.”

Based on a review of literature and policies on trauma-informed and comprehensive prevention, there is a clear “need for each educational institution to commit to the meaningful discipline,” the paper says -- including “serious sanctions involving temporary or permanent separation, of those found responsible of sexual harassment from the campus, especially if they are faculty holding significantly greater formal and informal power over students.”

Anything less risks what’s been called institutional betrayal, or hurting stakeholder confidence.

Moreover, Cantalupo and Kidder argue, from a legal perspective, meaningful discipline is a method of both secondary and tertiary prevention and is closely linked to primary prevention. Referring to the two major federal laws that govern institutions’ handling of gender-based harassment and assault, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 and the Clery Act, the paper says that discipline is “a critical component of the comprehensive prevention approach that we argue Title IX and Clery/VAWA doctrine recognizes and requires educational institutions to adopt.”

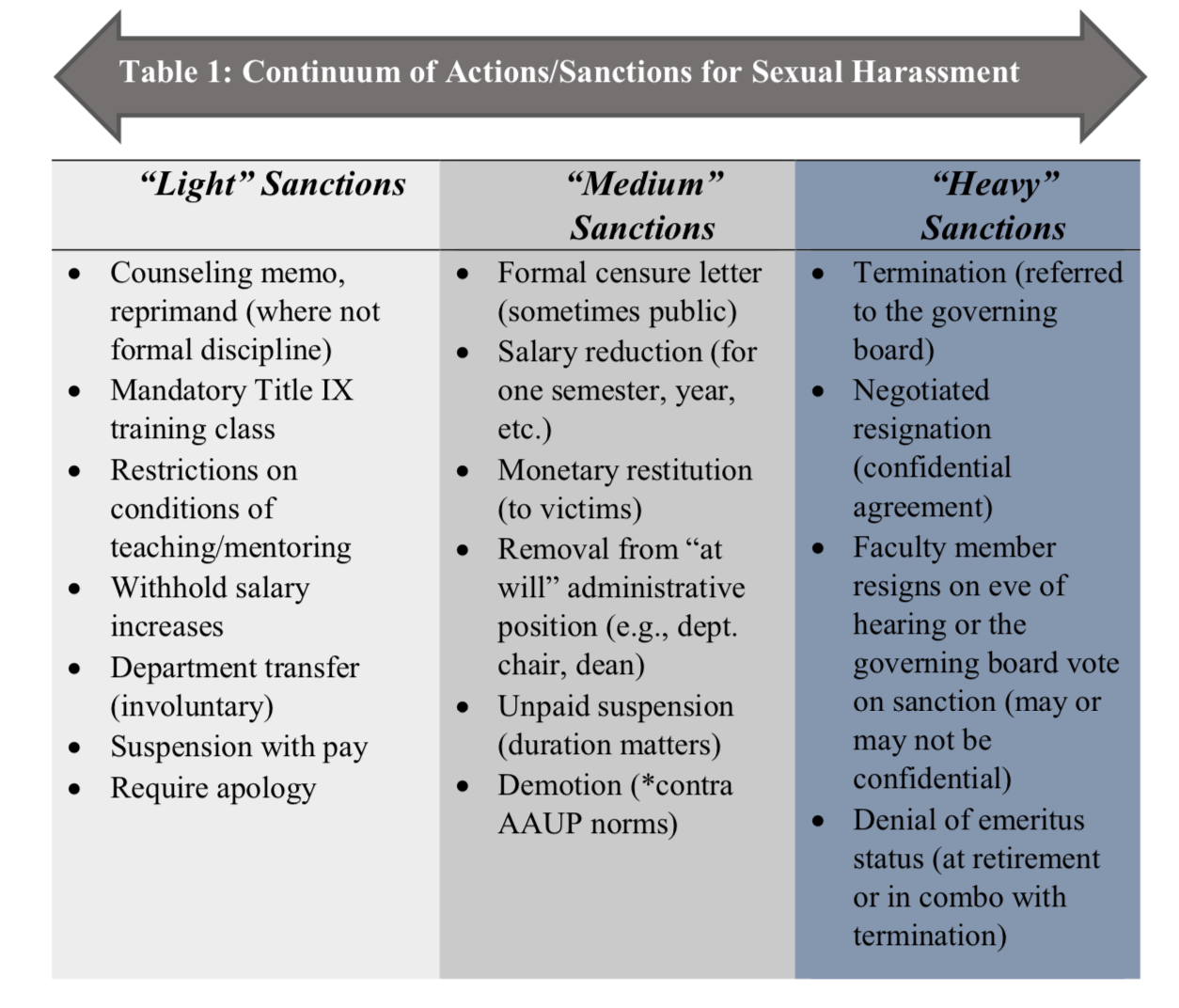

The paper includes a framework or spectrum that synthesizes institutions’ varied responses to harassment or assault, based on disciplinary codes, handbooks and other evidence. These responses range from “light” to “medium” to “heavy.” Light might be nothing at all, or retraining in sexual harassment policies. Medium could be removal from an administrative position, such as a chairship. Heavy could be resignation upon a board hearing or termination.

Source: Kidder and Cantalupo

Kidder and Cantalupo say that “experience shows that colleges and universities are hesitant to sanction seriously,” and that such hesitancy is particularly pronounced in cases involving a faculty member. Nevertheless, they argue, “there are few liability-related reasons for this timidity.”

In fact, they wrote, “no compelling legal reasons exist for not adopting sanctioning practices that promote comprehensive prevention of sexual harassment, including ones that accused sexual harassers experience as punitive.”

The article discusses confidential separation agreements and “pass the harasser” scenarios, which it says “raise difficult ‘collective action’ problems in academia.” Cantalupo and Kidder again recommend that institutional decision-making here be based on informed, comprehensive prevention-oriented practices, including greater engagement with accusers.

Regarding due process for accused professors, the authors recommend placing a faculty member on interim suspension while during investigations and faculty misconduct hearings.

This is all part of a public health approach, they argue -- and one that could also prevent “similar harms arising from other forms of discriminatory harassment.”

As for antiprevention syndrome, Kidder and Cantalupo list “a number of mutually reinforcing reasons (which are not rooted in retribution) why it is important for colleges and universities to both have and be seen as having a firm commitment to serious sanctions in faculty sexual harassment cases.” First, the absence of serious sanctions can reflect institutional failure to protect the real welfare of accusers, including students and junior faculty members.

Perceived “slaps on the wrist” -- such as those at California's Berkeley Campus, which became public in 2015 in the case of astronomer Geoff Marcy, who was found to have harassed multiple graduate students but was still allowed to teach -- also damage institutional credibility, they say. And clear discipline also serves as a deterrent for future abuses in that it “internalizes” institutional norms, since it’s “naïve to assume that effective training can prevent all” misconduct.

A major 2018 report on sexual harassment from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine also found that organizational climate is a top predictor of predatory behaviors.

Discipline can help alleviate accusers’ fears about retaliation for reporting their own experiences, the paper says. And, underscoring that colleges and universities are in the business of education, the paper notes that “student victims of and witnesses to sexual harassment will, if the conduct is not addressed swiftly and appropriately, receive a distorted education about ethical norms in higher education, which fosters cynicism and stunts their growth as potential future members of the professoriate.”

The paper included no formal quantitative analysis of known sanctions for faculty members -- other existing data indicate that many institutions have never formally terminated a tenured faculty member for sexual harassment or any other type of misconduct.

“This is true of approximately half of the University of California campuses over the last half century,” they say. “Moreover, multiple sources indicate that Harvard University has never fired a tenured professor for any type of misconduct in its storied history stretching back to 1638, even in the infamous 19th-century case of a faculty member who was hanged for murdering another Harvard professor.” (Harvard -- which is still facing criticism over how it handled a major harassment case -- did not immediately comment on that detail Monday.)

Kidder said Monday it was nevertheless his sense that over the past few years, there are signs of increased reporting and also institutions referring cases for disciplinary hearings.

“These are positive signs, and come with provisos about this being a preliminary observation, and about how far there is to go in the big scheme of things,” he said.